Blogging about my Torikae baya manga translation project.

Digression: Keeping track of time in Torikae baya

Something I’ve been doing as I’ve worked through the translation is noting indications of the passage of time in Torikae baya. The story takes place over several years, and while some of the jumps forward are made quite clear, there are other subtler indications too, and I want to make sure there’s nothing I’m missing! I’ll say a bit today about how much time has passed in the series so far and what kind of details I’ve looked at, but if you just want the basics, you can also take a look at the new timeline page I put together!

Something I’ve been doing as I’ve worked through the translation is noting indications of the passage of time in Torikae baya. The story takes place over several years, and while some of the jumps forward are made quite clear, there are other subtler indications too, and I want to make sure there’s nothing I’m missing! I’ll say a bit today about how much time has passed in the series so far and what kind of details I’ve looked at, but if you just want the basics, you can also take a look at the new timeline page I put together!

First, when does this take place? The original Torikaebaya monogatari was probably written in the late Heian or early Kamakura period, and the setting for the story is definitely some point in the Heian period. There have been a couple of times where I got into rabbit holes trying to work out exactly when the manga could be set based on things like dates of historical eclipses. I even concluded at one point that it wasn’t chronologically possible, because there are references to Yoshino no Miya having been on a mission to Tang China, but it’s also made clear that The Tale of Genji already exists.

The end result of all this is that I don’t really know! Maybe the Tang reference is just outdated terminology for the time period, or maybe the timing really isn’t intended to be very specific.

But at least on a closer level, we can work out some details about the timeline! Early on, it’s made quite clear how much time passes: the story starts with Sara and Suiren being born, the major kidnapping incident takes place six years later, and the discussions about Fujiwara no Marumitsu’s son taking a job at court begin when the siblings are almost 14 – time for becoming an adult, as far as everyone in this setting is concerned. The next clear indication of characters’ ages comes in Episode 6, when we hear that Shi no Hime – 19 years old – is three years Sara’s senior. Otherwise, we generally have to rely on other clues.

I want to come back to the point about coming of age though. It’s worth noting that Sara and Suiren are pretty young, at least by the standards a lot of us would expect. This also applies to other characters. Tsuwabuki mentions once that he is 18, and soon afterwards he says that Sara is still 16 at that point, so they’re just two years apart. We don’t know Nanten no Togu’s age, but she’s noted as seeming like a child despite her astuteness, so it’s probably fair to assume she isn’t too far away from Sara and Suiren’s age.

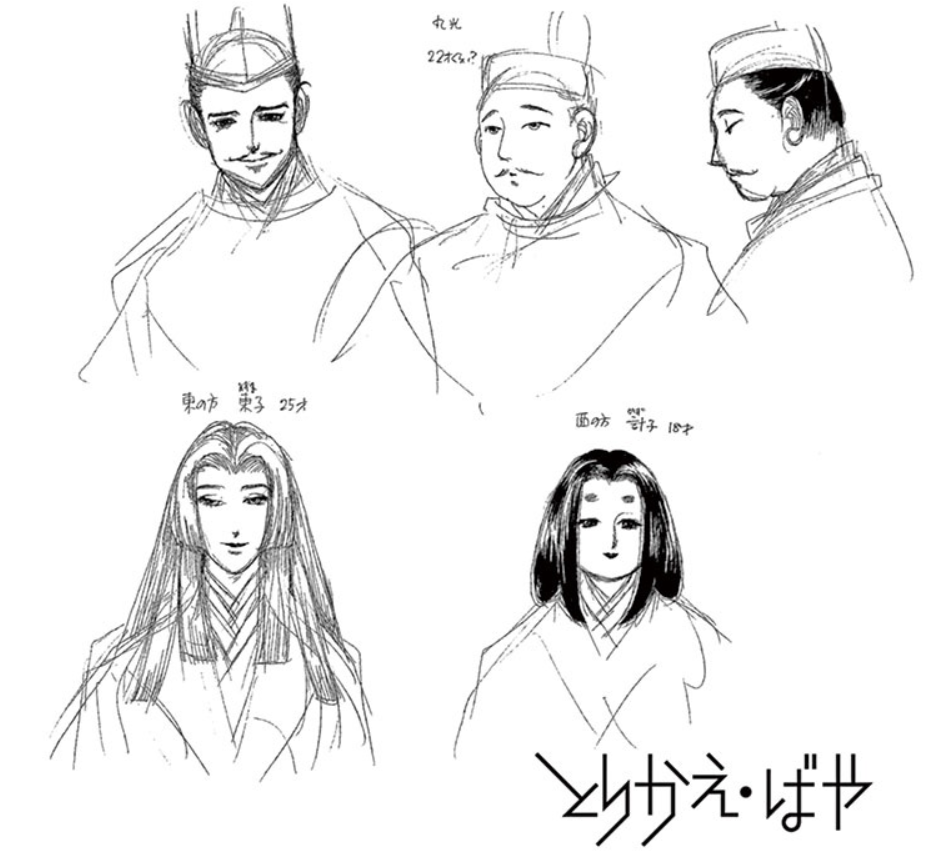

Production sketches of characters from volume 1, page 150.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

There are no in-text references to the age of Sara and Suiren’s parents, but there are some sketches included between chapters in Volume 1 that can help. There’s a sketch of Marumitsu, supposedly around 22 years old, and I think it’s fair to assume that’s as of when the siblings are born. There are also drawings of his wives, with Higashi no Ue (Suiren’s mother) at 25 years old and Nishi no Ue (Sara’s mother) at 18. This aligns quite well with the ages at which Sara and Suiren are entering adult life: if they can start working at 14 and get married at 16, it’s not so bizarre that they’d be having children somewhere around 20.

And as for other signs of the passage of time, we can look at details like seasonal events. The komahiki that takes place in Episode 2 is supposed to have been an August event, so it must be within the first few months of Sara entering the work force. The fact that the changing of the Emperors is specified to take place at New Year also helps set up the chronology of some of what follows.

After that, another thing I found myself looking at obsessively was flowers. Around the time of Sara’s marriage to Shi no Hime and Suiren starting her job as naishi no kami, we know that not much time has passed since New Year, because we see snow and because there’s a plum blossom party at the palace with the appearance of a notably unseasonable butterfly. In the next couple of chapters, there are frequent mentions of the cherry blossoms – showing that spring has come – and even more specific points like how far into the season it is, and the appearance of wisteria which typically comes just after.

I won’t write out everything that I’ve considered with respect to the timeline, but I promise there’s a lot! Again, please do check out the timeline page if you want to get a quick idea of what happens when – and I’ll be keeping it updated too!

Thoughts from Episode 2: Beauties and Cuties

This week’s post looks at the second chapter of Torikae baya, and some thoughts about aesthetics and vocabulary choices.

Episode 2 opens with Sara and Suiren at the age of 14, going through their genpuku and mogi ceremonies respectively – in the afterword of volume 3, Saito points out that these specifically gendered rites are the predecessors of the modern-day Seijin no Hi.

This week’s post looks at the second chapter of Torikae baya, and some thoughts about aesthetics and vocabulary choices.

Episode 2 opens with Sara and Suiren at the age of 14, going through their genpuku and mogi ceremonies respectively – in the afterword of volume 3, Saito points out that these specifically gendered rites are the predecessors of the modern-day Seijin no Hi. These are attended by Marumitsu’s slightly more angular brother Kakumitsu, and the brothers’ father, who doesn’t have a catchy individual name, so I’ve been calling him Fujiwara Senior in the translation so far (and Jijimitsu in my head!). Kakumitsu and Fujiwara are both clueless about Sara and Suiren’s secret, with Kakumitsu musing that Sara would make a great son-in-law and Fujiwara believing that Suiren’s beauty will catch the eye of even the Emperor. We also learn around this point that Sara and Suiren have even more names, with Marumitsu saying that Sara will “borrow” the name of Fujiwara no Tsukimitsu from Suiren and “lend” Suiren the name Suzushiko.

Next, Sara goes for his first day at work. The Emperor is so impressed that he immediately gives Sara a new job as his chamberlain (侍従). Sara begins to worry once he learns that nobody else at court is like him, but otherwise, everything is going well for him at work. On the day of the komahiki ceremony, we’re introduced to Colonel Tsuwabuki, another popular young man at court. When Sara manages to be even more impressive and dashing than him, Tsuwabuki chases him down to announce that the two are now to be best buddies, and that he hears Sara has an identical sister (😉) he’d like to meet.

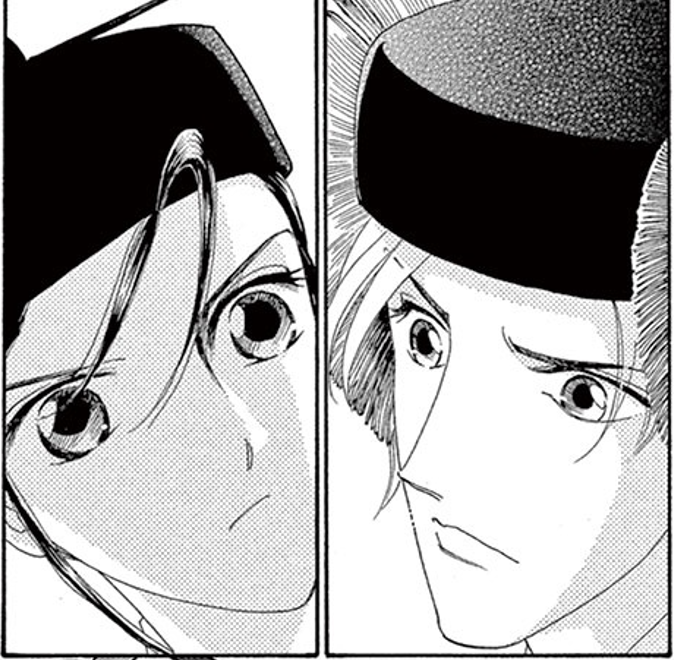

How to make friends as a young gentleman in the Heian period.

Panels from volume 1, page 76. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

Something that might strike you here is that everyone is beautiful! This is partly down to the art style, but it’s also something that comes up constantly in the dialogue. Old Man Fujiwara compares Suiren’s beauty to the mythical Princess Kaguya; meanwhile, young men like Sara and Tsuwabuki are also regarded as beautiful. I try not to translate 美しい (utsukushii) as “beautiful” every single time, but even if I don’t, the word still comes up a lot.

This reflects the Heian court’s preoccupation with beauty in various forms: aesthetic appeal, but also good taste and manners. We’ll see more examples of what Ivan Morris called the Heian court’s cult of beauty throughout the series, with Sara and the men being accomplished musicians and poets, and Suiren and Nanten no Togu being avid readers. This is what we know mattered to the ruling class, and it’s also what a lot of people today will be expecting from art related to the Heian period. Basically, it’s obvious that everyone should be beautiful in a Heian court romance!

But while I’ve mostly been thinking about 美しい so far, that isn’t the only way that people are described. We see all kinds of different terms, and although most of them seem reasonable enough in a piece of historical fiction, there’s one that seems to stick out: かわいい (kawaii). It’s not as if this is actually too modern, but it feels like it is – especially when it’s repeatedly followed with a little heart symbol. There’s some sense of deliberate anachronism that overrides my instinct to avoid translating it as “cute” in a historical setting. For example:

We see a closeup of SARA, then the reaction of the COURT LADIES.

SARA [thinking] Tsuwabuki no Kimi?

LADY 1 Oh, look! Sarasoju no Kimi is here!

LADY 2 What a cutie! ❤

TSUWABUKI glances at SARA, who is taken by surprise. In the background, the LADIES are still excited.

A LADY [aside] ❤

Obviously, the manga isn’t actually written in classical Japanese, but it’s interesting to see these points that seem to draw attention to the fact that it’s in modern Japanese. Another example that stands out is in the next chapter, when one of Tsuwabuki’s friends uses the obviously post-1990s word 萌える (moeru). I’ll have to write a whole other blog post about “moe” at some point, but what I want to say for now is that this, like the other little anachronistic dialogue moments, serves to make the characters more relatable. A lot of the time, they use archaic expressions or structures that situate them in the past, but when they describe the beauty around them in the same way that a reader might describe the beauty of the manga art, it feels like they aren’t so far away.