Blogging about my Torikae baya manga translation project.

Thoughts from Episode 3: The Eclipse

After Episode 2 showed Sara starting his exciting new job working for the Emperor and meeting his new best friend (whether he likes it or not) Tsuwabuki, this chapter gets a bit more dramatic. Tsuwabuki shows up uninvited at Sara’s home with two of his friends, and gets terribly upset that Sara won’t introduce him to Suiren. As it turns out, everybody has heard about Suiren, even the Emperor! This causes Sara to have (apparently for the first time in a while) a nightmare about the tengu from Episode 1. The tengu tells Sara that he and Suiren are cursed, and that the curse will be lifted when the tengu devours the Emperor.

After Episode 2 showed Sara starting his exciting new job working for the Emperor and meeting his new best friend (whether he likes it or not) Tsuwabuki, this chapter gets a bit more dramatic. Tsuwabuki shows up uninvited at Sara’s home with two of his friends, and gets terribly upset that Sara won’t introduce him to Suiren. As it turns out, everybody has heard about Suiren, even the Emperor! This causes Sara to have (apparently for the first time in a while) a nightmare about the tengu from Episode 1. The tengu tells Sara that he and Suiren are cursed, and that the curse will be lifted when the tengu devours the Emperor.

Three important men then show up from the on’yoryo (for now at least, I have this as the Bureau of Yin and Yang – this is where they practised divination, astrology, etc) to reveal that an annular eclipse is coming, and the Emperor immediately falls ill. While everyone in the palace prepares to hide him away from the ominous effects of the eclipse, the Emperor gives his younger brother (Togu, the crown prince) a crystal ball containing an image of Kundali, one of the Five Wisdom Kings. Sara, inspired by another vision of the tengu, decides to risk being cursed by the eclipse in order to break his own curse, and is soon joined by Tsuwabuki and Togu. They go to the roof of a high building, where Togu holds out the crystal ball and prays for rain. Clouds come and obscure the eclipse, and the Emperor recovers.

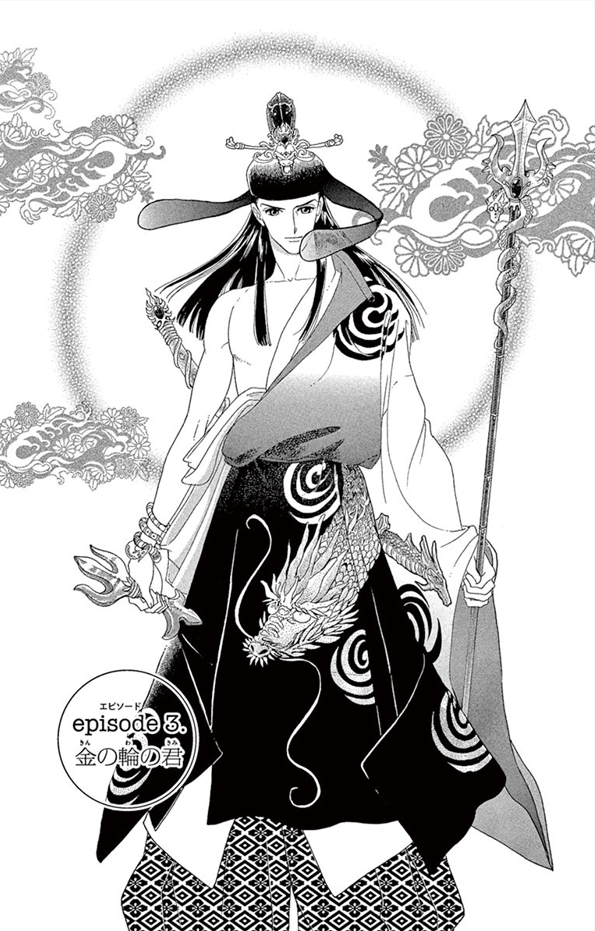

Title page of Episode 3 from volume 1, page 83. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

There are plenty of things to think about in this chapter! There’s new information about the tengu’s curse and how that ties into other aspects of the story, as well as plenty of details about the belief system at the court. Today, though, I’ll just take a look at the chapter’s title – which is quite enough to handle!

Episode 3 is titled 「金の輪の君」 (kin no wa no kimi). This is quite a bit more abstract than previous titles, which were just characters’ names. The meaning of “kin no wa” becomes clear when characters begin talking about the eclipse. The astrologers talk about a 金の環の日食 (kin no wa no nisshoku), referring to the annular eclipse. Usually this is written without the のs, as 金環日食 (kinkan nisshoku), but it’s same in practice, qualifying the eclipse (nisshoku) as one where a golden ring (kin no wa) is visible.

You might notice – not that I did at first! – that the spelling in the dialogue uses the kanji 環 where the title uses 輪. I was trying to figure out what difference this would make and why it would be worth writing it two ways, but I think it’s most likely for practical reasons. In the title, it’s standing alone, and as 輪 is more commonly used for “ring” as a noun, it makes a bit more sense in that context. On the other hand, when it appears again later, it’s in the full “annular eclipse” phrase. It uses the same words, and with the same meaning, but “kinkan nisshoku”, the usual term for an annular eclipse, uses the more abstract 環 and can’t be written with a 輪. Perhaps there is more to it, but that’s the only reason I can see for writing it two different ways.

Another side point here is about the word for eclipse itself: 日食, meaning that the sun is eaten. There are old Chinese myths about monsters eating the sun during an eclipse, including a black dog called the tiangou. This is written as 天狗, the same spelling as “tengu”, which in Japan came to be seen as birdlike monsters such as the ones we see pretty regularly in Torikae baya. So when the dream-tengu tells Sara it’s going to devour the Emperor – whom the people at the court handily point out is symbolised by the sun – it connects closely with old myths about eclipses.

Anyway, what about that title? How should it be translated? As we have the “kin no wa” but not the “nisshoku”, it doesn’t really seem right to translate this as “eclipse”. That would be providing information that the Japanese readers aren’t getting at this point. “Annulus” could make sense as that’s the part that is mentioned, but the fact it’s written as 金の輪 and not 金環 puts me off that too. And there’s a later line that makes me feel that it could be intended to evoke the idea of a halo as well, which then gels with the imagery of the title page. This all makes me lean towards a fairly literal answer, so that I’m not saying more than I should, and so that it remains mysterious. In the end, I came up with “He of the Golden Ring” – interpreting the “kimi” in the same way as it gets used as a term of respect in people’s (usually men’s) names.

I’m just glad not every translation choice is as complicated as this!

Thoughts from Episode 2: Beauties and Cuties

This week’s post looks at the second chapter of Torikae baya, and some thoughts about aesthetics and vocabulary choices.

Episode 2 opens with Sara and Suiren at the age of 14, going through their genpuku and mogi ceremonies respectively – in the afterword of volume 3, Saito points out that these specifically gendered rites are the predecessors of the modern-day Seijin no Hi.

This week’s post looks at the second chapter of Torikae baya, and some thoughts about aesthetics and vocabulary choices.

Episode 2 opens with Sara and Suiren at the age of 14, going through their genpuku and mogi ceremonies respectively – in the afterword of volume 3, Saito points out that these specifically gendered rites are the predecessors of the modern-day Seijin no Hi. These are attended by Marumitsu’s slightly more angular brother Kakumitsu, and the brothers’ father, who doesn’t have a catchy individual name, so I’ve been calling him Fujiwara Senior in the translation so far (and Jijimitsu in my head!). Kakumitsu and Fujiwara are both clueless about Sara and Suiren’s secret, with Kakumitsu musing that Sara would make a great son-in-law and Fujiwara believing that Suiren’s beauty will catch the eye of even the Emperor. We also learn around this point that Sara and Suiren have even more names, with Marumitsu saying that Sara will “borrow” the name of Fujiwara no Tsukimitsu from Suiren and “lend” Suiren the name Suzushiko.

Next, Sara goes for his first day at work. The Emperor is so impressed that he immediately gives Sara a new job as his chamberlain (侍従). Sara begins to worry once he learns that nobody else at court is like him, but otherwise, everything is going well for him at work. On the day of the komahiki ceremony, we’re introduced to Colonel Tsuwabuki, another popular young man at court. When Sara manages to be even more impressive and dashing than him, Tsuwabuki chases him down to announce that the two are now to be best buddies, and that he hears Sara has an identical sister (😉) he’d like to meet.

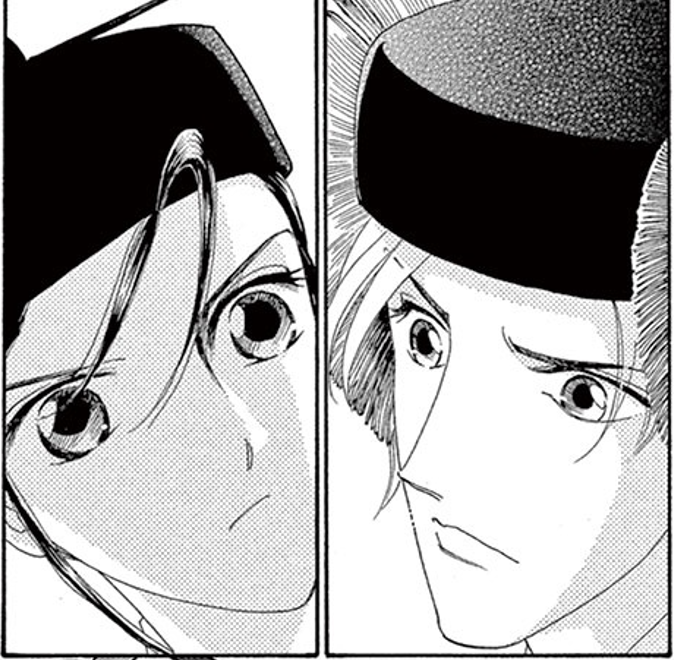

How to make friends as a young gentleman in the Heian period.

Panels from volume 1, page 76. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

Something that might strike you here is that everyone is beautiful! This is partly down to the art style, but it’s also something that comes up constantly in the dialogue. Old Man Fujiwara compares Suiren’s beauty to the mythical Princess Kaguya; meanwhile, young men like Sara and Tsuwabuki are also regarded as beautiful. I try not to translate 美しい (utsukushii) as “beautiful” every single time, but even if I don’t, the word still comes up a lot.

This reflects the Heian court’s preoccupation with beauty in various forms: aesthetic appeal, but also good taste and manners. We’ll see more examples of what Ivan Morris called the Heian court’s cult of beauty throughout the series, with Sara and the men being accomplished musicians and poets, and Suiren and Nanten no Togu being avid readers. This is what we know mattered to the ruling class, and it’s also what a lot of people today will be expecting from art related to the Heian period. Basically, it’s obvious that everyone should be beautiful in a Heian court romance!

But while I’ve mostly been thinking about 美しい so far, that isn’t the only way that people are described. We see all kinds of different terms, and although most of them seem reasonable enough in a piece of historical fiction, there’s one that seems to stick out: かわいい (kawaii). It’s not as if this is actually too modern, but it feels like it is – especially when it’s repeatedly followed with a little heart symbol. There’s some sense of deliberate anachronism that overrides my instinct to avoid translating it as “cute” in a historical setting. For example:

We see a closeup of SARA, then the reaction of the COURT LADIES.

SARA [thinking] Tsuwabuki no Kimi?

LADY 1 Oh, look! Sarasoju no Kimi is here!

LADY 2 What a cutie! ❤

TSUWABUKI glances at SARA, who is taken by surprise. In the background, the LADIES are still excited.

A LADY [aside] ❤

Obviously, the manga isn’t actually written in classical Japanese, but it’s interesting to see these points that seem to draw attention to the fact that it’s in modern Japanese. Another example that stands out is in the next chapter, when one of Tsuwabuki’s friends uses the obviously post-1990s word 萌える (moeru). I’ll have to write a whole other blog post about “moe” at some point, but what I want to say for now is that this, like the other little anachronistic dialogue moments, serves to make the characters more relatable. A lot of the time, they use archaic expressions or structures that situate them in the past, but when they describe the beauty around them in the same way that a reader might describe the beauty of the manga art, it feels like they aren’t so far away.

Digression: Who’s who in Torikae baya?

Something slightly different this week! So far I’ve been talking about quite a few different characters in Torikae baya, and I’ll be talking about many more in future posts. With that in mind, I want to give a bit of an overview of who makes up the cast of the manga, and who each character’s counterpart is in Torikaebaya monogatari.

Something slightly different this week! So far I’ve been talking about quite a few different characters in Torikae baya, and I’ll be talking about many more in future posts. With that in mind, I want to give a bit of an overview of who makes up the cast of the manga, and who each character’s counterpart is in Torikaebaya monogatari.

First, we have the protagonists, Sarasoju (沙羅双樹) and Suiren (睡蓮). In the manga, each is named after flowers blooming nearby at the time of their birth: sarasoju is the sal tree, which is associated with the death of the Buddha, and suiren is the water lily. Family members tend to abbreviate “Sarasoju” to “Sara”, while his colleague Tsuwabuki calls him “Soju”. In Torikaebaya monogatari, neither sibling has a personal name and both are referred to by their job titles, Sara’s counterpart being a chunagon (中納言) and Suiren’s being a naishi no kami (尚侍) for most of the story.

Their father is Fujiwara no Marumitsu (藤原丸光). As in Torikaebaya monogatari, the father begins the story as a gondainagon (権大納言), with a brother (Kakumitsu, 角光, in the manga) who is the udaijin (右大臣). Fitting these names, Saito draws Marumitsu with rounder features and Kakumitsu with sharper features, but they otherwise look very similar.

Marumitsu has a wife in each wing of his residence, and each of them is mother to one of the protagonists. In the original story and in Torikae baya, his brother has four daughters: the two eldest are involved with the current Emperor and Crown Prince, and the youngest, called Shi no Hime (四の姫) in the manga, marries Sara.

Another major character is the chunagon’s amorous and troublemaking colleague, whose rank for most of the story is saisho no chujo (宰相中将). As with some of the other major characters, Saito gives him a more memorable name: Tsuwabuki (石蕗).

In both versions, the current Emperor abdicates early on in the story, allowing the Crown Prince (東宮) to take his place. Neither having a male heir, the title of 東宮 shifts to the abdicated Emperor’s daughter, who becomes known as 女東宮 (basically, “girl crown prince” – fascinatingly, the Nihon Kokugo Daijiten lists Torikaebaya monogatari as the earliest known appearance of this term). So far, I’ve been pencilling in both her and the first Crown Prince with the transliteration Togu.

Some characters in Torikae baya do have counterparts in the original story but are otherwise different in significant ways. Umetsubo (梅壺) is a member of the abdicated Emperor’s harem who, in Torikaebaya monogatari, appears just once, and we learn nothing about her, but in Torikae baya, she becomes a major antagonist.

Yoshino no miya (吉野の宮)’s counterpart in the original tale shares a similar backstory, but notably has two half-Chinese daughters; in Torikae baya, he is instead implied to be another character’s father (I won’t say whose just yet!).

One more example is the manga character San no Hime (三の姫), who plays quite a big role in the second half of the series, but is based on a character who is only ever really implied in the original – the udaijin’s unaccounted-for third daughter.

And this is definitely not an exhaustive list! Plenty more characters are identified throughout the manga, but these are at least most of the major ones. As you often see in a multi-volume series, there are handy relationship charts to kick off most volumes. At some point down the line, I might try to throw together an expanded version of those myself!

More thoughts from Episode 1: The Tengu of Kurama

It took a bit of time to get writing a follow-up to the previous post, because this time last week I was at the JF/BAJS PhD workshop! I talked about my project and heard some great presentations from other postgraduate students working on all kinds of different topics. One thing I prepared for my presentation but didn’t quite have time to elaborate on was Saito’s use of tengu as a recurring motif in Torikae baya. The first appearance of a tengu is in Episode 1, so I’ll say a bit about that today!

It took a bit of time to get writing a follow-up to the previous post, because this time last week I was at the JF/BAJS PhD workshop! I talked about my project and heard some great presentations from other postgraduate students working on all kinds of different topics. One thing I prepared for my presentation but didn’t quite have time to elaborate on was Saito’s use of tengu as a recurring motif in Torikae baya. The first appearance of a tengu is in Episode 1, so I’ll say a bit about that today!

In Torikaebaya monogatari, there is a section in the middle of the story where the chunagon (Sarasoju’s counterpart) leaves Heian-kyo and the naishi no kami (Suiren’s counterpart) goes in search of him. During this time, their father is worried sick – mainly about the chunagon, because the naishi no kami’s role is so behind-closed-doors that nobody even notices she’s gone. The naishi no kami goes to Yoshino, learns that the chunagon is in Uji, and has the bright idea for them to switch roles and return to ease their father’s worries. Just as the naishi no kami is coming back to tell him the good news, the father has a dream. In the dream, he is told that his children were the way they were because of a tengu’s curse (“goblin” in Willig’s translation), but now the curse has been lifted and they will take on their “proper” roles.

This is the first and last mention of a tengu in the original story, but Saito takes it much further, presenting the tengu’s curse as something that Sara and Suiren themselves are worried about throughout the series. In Episode 1, we first encounter tengu when a young Sara and Suiren are on their way to the temple in Kurama, north of Heian-kyo, where their father Marumitsu hopes their odd behaviour can be set right. Kurama has a long association with tengu, and though that isn’t specified in the manga, Sara does remark on having heard tales of tengu descending from the mountains to snatch up children. Mountain locations, and especially the yamabushi (mountain ascetics) found there, are another link to tengu that will be important later in the manga.

Panel from volume 1, page 27. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

During the journey to Kurama, a gang of apparent tengu show up to ransack the palanquins, unceremoniously killing the servants in the process. They’re disappointed not to find much of value, with the exception of two pretty kids they can sell to some unnamed lecherous priest. Sara comes up with a risky escape plan: if the two switch clothes, Sara can attack/distract the tengu, allowing them both to run away. And it works! Sara discovers that the bandits can’t fly and aren’t real tengu, and he manages to lead Suiren to safety. This is a crucial moment, showing us that Sara and Suiren are better for not fitting their expected gender roles. It also sets up tengu as a source of fear, and as something that maybe is and maybe isn’t real.

Nowadays, tengu are often portrayed as generally humanoid but red and with an extremely long nose – and something like this does appear once later in Torikae baya – but this image is a comparatively recent development. In contrast, the gang of bandits that appear in this chapter wear beaklike masks and yamabushi-esque garments, and have unkempt hair. I’m not totally sure if all of these aspects are accurate to the time period, but the idea of tengu as sneaky bird-men who kidnap people existed by the time of Konjaku monogatarishu, which is from roughly the same time as Torikaebaya monogatari (late Heian).

Anyway, that’s as much as I’ll get into about tengu today, but you can expect to hear more about them soon!

Thoughts from Episode 1: Introduction to the story, and court ranks

Here’s the first blog post proper! I’ll be going through my thoughts from translating Saito Chiho’s Torikae baya, starting at the beginning. If you happen to have access to the manga in Japanese, you can even follow along!

First, I’ll quickly introduce the story. The manga is based on Torikaebaya monogatari, a tale written by an unknown author or authors (there was originally more than one version) in probably the late Heian period – at the very least, it’s set in the Heian period. In both the original story and the manga, a court official has two wives, each of whom gives birth on the same day to almost identical babies, one a girl and one a boy. This is all very auspicious for the father, who would hope that they can grow up to fill important roles, but there’s a catch: his new “daughter” behaves like a boy and his new “son” behaves like a girl.

Here’s the first blog post proper! I’ll be going through my thoughts from translating Saito Chiho’s Torikae baya, starting at the beginning. If you happen to have access to the manga in Japanese, you can even follow along!

First, I’ll quickly introduce the story. The manga is based on Torikaebaya monogatari, a tale written by an unknown author or authors (there was originally more than one version) in probably the late Heian period – at the very least, it’s set in the Heian period. In both the original story and the manga, a court official has two wives, each of whom gives birth on the same day to almost identical babies, one a girl and one a boy. This is all very auspicious for the father, who would hope that they can grow up to fill important roles, but there’s a catch: his new “daughter” behaves like a boy and his new “son” behaves like a girl.

とりかへばや! the man says to himself – approximately “I wish I could switch them.” They’d be perfect if they were the other way around, but they just won’t change. Time goes by, and people start to assume that the “daughter” is really the man’s son. Rumour spreads about this charming, talented boy, and the father is asked to have him come of age and take up a job at the court. He can’t convince his children to change, and he can’t refuse the request, so it is decided that the child will live as a young man. Soon, the other child has the coming-of-age ceremony for a young woman, and becomes a naishi no kami, an important attendant to the new crown princess.

The two siblings earn constant praise, but it isn’t long before romantic issues start to derail their success. The young man is caught up in a love triangle with his new wife and an amorous colleague who is simultaneously obsessed with him, his wife AND his rumoured identical sister. Meanwhile, the naishi no kami falls in love with the crown princess. After all sorts of drama, the siblings leave the capital, believing there is no way they can return – until they decide to trade places.

Now taking on each other’s former roles, they return and sort out all their romantic entanglements, with most people none the wiser. In the original story, they mostly just resolve their earlier problems at this point, before living happily ever after in influential positions with desirable spouses. The Torikae baya manga takes a longer route to the ending, featuring high-stakes political intrigue after the siblings’ return to the capital, but the story is the same by and large.

Unlike the original tale, Torikae baya is split up into chapters (named “episodes”) which were published monthly in Gekkan Flowers. Making each chapter compelling seems to me to have been a key motivation for making changes to the story. Episode 1: Sara and Suiren covers a lot of ground, starting with the siblings’ birth and ending just before they come of age – and finding time for a major incident in between that doesn’t happen in the older tale.

What I want to talk about today is names and titles. Titles for ranks and job positions are of huge importance in Torikaebaya monogatari, because in the original tale, that is how characters are always referred to. Rather than personal names, they get called things like “Gondainagon” and “Saisho no chujo”, and these change as they receive promotions during the story. This feature is not necessarily preserved in modern Japanese translations and adaptations, including Torikae baya. Saito names the court official with the two wives Fujiwara no Marumitsu, while his boyish daughter is Sarasoju (most often abbreviated to “Sara”) and his girlish son is Suiren. As the manga continues, more named characters also appear.

Still, this isn’t to say that titles are totally done away with. Some characters are still always referred to by their official position. Meanwhile, other people tend to refer to Marumitsu, Sarasoju, Suiren and others with titles. And that means I need to translate them!

Just a few pages into Episode 1, we get a salvo of official titles to let readers know what big shots Marumitsu and his family are:

男の名は藤原丸光

父親は元・関白

兄は右大臣

本人は権大納言にして近衛大将という超上流貴族

(Torikae baya, volume 1, page 7)

There are a few options for how to tackle these:

Transliterate. This little bit of narration feels like it’s supposed to be at least a little bit bewildering, even for Japanese readers. It reminds us that we’re dealing with a society most readers aren’t all that familiar with, so maybe in English, they should stay as they are.

Use an existing translation. Other classical Japanese works have been translated into English, including Torikaebaya monogatari. In Rosette F Willig’s translation from the late 1970s (it’s a bit complicated in the version later published as The Changelings in 1983), these job titles are all translated, and keeping the same translations could clarify the connections between the two texts.

Come up with my own. Relying on Willig’s terms and her source for these terms is all well and good, but what if I disagree on some of them? What if I encounter one that doesn’t appear in the original tale?

Ultimately, I still don’t know what I’ll settle on. Transliterating is the easiest way, and in some cases it might be no harder to understand than an English term, but on the other hand, they do have practical functions which could be lost that way.

For now, I’ve been making my own, mapping them onto similar positions in other government systems or militaries. Helpfully, in one “Atogaki baya” section (brief afterwords in manga form that appear at the end of each collected volume), Saito has a little chart of relative positions, so I can hopefully avoid translating a term one way only to realise later that it suits another position better. I’ll work on devising a system I’m happy with. These might even work out to be much the same as Willig’s translations!

And so, to finish off, here’s what my translation of the quoted section above looks like right now:

His name was Fujiwara no Marumitsu, and he belonged to the upper echelons of society.

His father was the former Chief Advisor to the Emperor.

His older brother was the Vice Chancellor.

And Marumitsu himself was a Provisional Upper Councillor of State and General of the Imperial Guards.

Thanks for reading!

Welcome!

Welcome to the blog! Please take a look at the about page to learn more about this project.

Welcome to the blog! Please take a look at the about page to learn more about this project.

I’ll be aiming to post at least once a week with updates about my ongoing English translation of Torikae baya by Saito Chiho. Feel free to post a comment or reach out if you ever have any questions or comments!