Blogging about my Torikae baya manga translation project.

Digression: Keeping track of time in Torikae baya

Something I’ve been doing as I’ve worked through the translation is noting indications of the passage of time in Torikae baya. The story takes place over several years, and while some of the jumps forward are made quite clear, there are other subtler indications too, and I want to make sure there’s nothing I’m missing! I’ll say a bit today about how much time has passed in the series so far and what kind of details I’ve looked at, but if you just want the basics, you can also take a look at the new timeline page I put together!

Something I’ve been doing as I’ve worked through the translation is noting indications of the passage of time in Torikae baya. The story takes place over several years, and while some of the jumps forward are made quite clear, there are other subtler indications too, and I want to make sure there’s nothing I’m missing! I’ll say a bit today about how much time has passed in the series so far and what kind of details I’ve looked at, but if you just want the basics, you can also take a look at the new timeline page I put together!

First, when does this take place? The original Torikaebaya monogatari was probably written in the late Heian or early Kamakura period, and the setting for the story is definitely some point in the Heian period. There have been a couple of times where I got into rabbit holes trying to work out exactly when the manga could be set based on things like dates of historical eclipses. I even concluded at one point that it wasn’t chronologically possible, because there are references to Yoshino no Miya having been on a mission to Tang China, but it’s also made clear that The Tale of Genji already exists.

The end result of all this is that I don’t really know! Maybe the Tang reference is just outdated terminology for the time period, or maybe the timing really isn’t intended to be very specific.

But at least on a closer level, we can work out some details about the timeline! Early on, it’s made quite clear how much time passes: the story starts with Sara and Suiren being born, the major kidnapping incident takes place six years later, and the discussions about Fujiwara no Marumitsu’s son taking a job at court begin when the siblings are almost 14 – time for becoming an adult, as far as everyone in this setting is concerned. The next clear indication of characters’ ages comes in Episode 6, when we hear that Shi no Hime – 19 years old – is three years Sara’s senior. Otherwise, we generally have to rely on other clues.

I want to come back to the point about coming of age though. It’s worth noting that Sara and Suiren are pretty young, at least by the standards a lot of us would expect. This also applies to other characters. Tsuwabuki mentions once that he is 18, and soon afterwards he says that Sara is still 16 at that point, so they’re just two years apart. We don’t know Nanten no Togu’s age, but she’s noted as seeming like a child despite her astuteness, so it’s probably fair to assume she isn’t too far away from Sara and Suiren’s age.

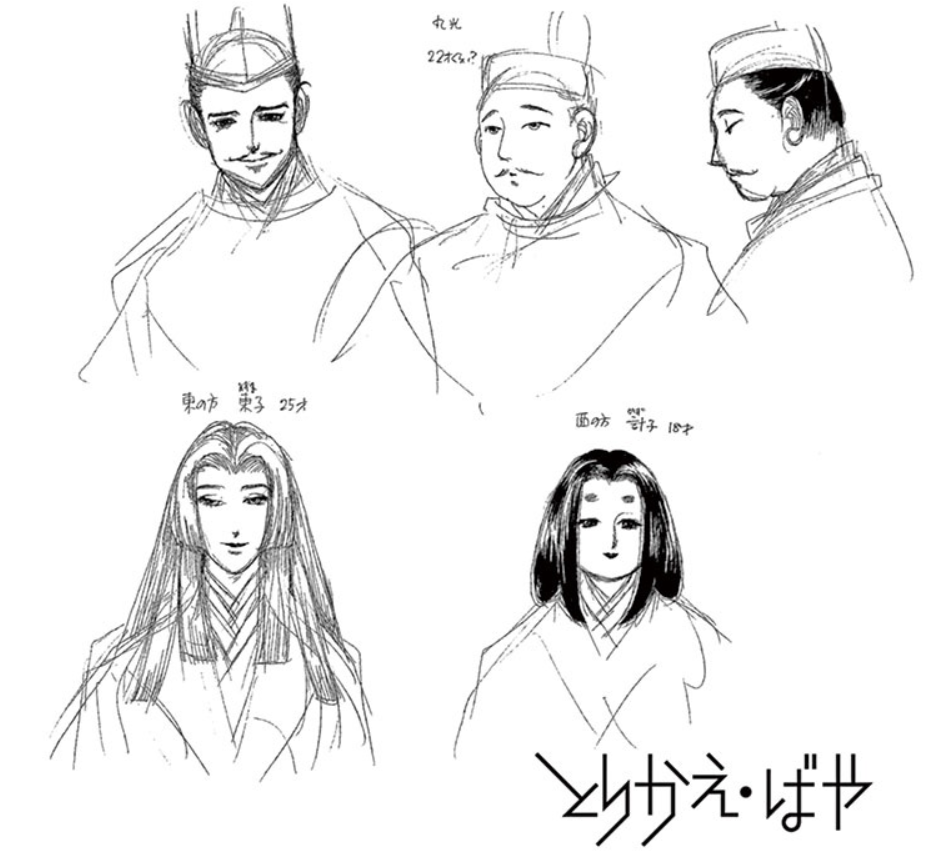

Production sketches of characters from volume 1, page 150.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

There are no in-text references to the age of Sara and Suiren’s parents, but there are some sketches included between chapters in Volume 1 that can help. There’s a sketch of Marumitsu, supposedly around 22 years old, and I think it’s fair to assume that’s as of when the siblings are born. There are also drawings of his wives, with Higashi no Ue (Suiren’s mother) at 25 years old and Nishi no Ue (Sara’s mother) at 18. This aligns quite well with the ages at which Sara and Suiren are entering adult life: if they can start working at 14 and get married at 16, it’s not so bizarre that they’d be having children somewhere around 20.

And as for other signs of the passage of time, we can look at details like seasonal events. The komahiki that takes place in Episode 2 is supposed to have been an August event, so it must be within the first few months of Sara entering the work force. The fact that the changing of the Emperors is specified to take place at New Year also helps set up the chronology of some of what follows.

After that, another thing I found myself looking at obsessively was flowers. Around the time of Sara’s marriage to Shi no Hime and Suiren starting her job as naishi no kami, we know that not much time has passed since New Year, because we see snow and because there’s a plum blossom party at the palace with the appearance of a notably unseasonable butterfly. In the next couple of chapters, there are frequent mentions of the cherry blossoms – showing that spring has come – and even more specific points like how far into the season it is, and the appearance of wisteria which typically comes just after.

I won’t write out everything that I’ve considered with respect to the timeline, but I promise there’s a lot! Again, please do check out the timeline page if you want to get a quick idea of what happens when – and I’ll be keeping it updated too!

Thoughts from Episode 10: Tsuwabuki, no!

A little bit of time has passed since the previous chapter, and now we see that Sara and Shi no Hime are getting along better: Sara brings her a nest of orphaned chicks to raise, they watch the moon together, and Shi no Hime calls Sara “se no kimi” (背の君), which Saito helpfully notes as a term of endearment for one’s husband. At night, though, Sara worries that he isn’t doing enough, while Shi no Hime worries that he might not really love her.

A little bit of time has passed since the previous chapter, and now we see that Sara and Shi no Hime are getting along better: Sara brings her a nest of orphaned chicks to raise, they watch the moon together, and Shi no Hime calls Sara “se no kimi” (背の君), which Saito helpfully notes as a term of endearment for one’s husband. At night, though, Sara worries that he isn’t doing enough, while Shi no Hime worries that he might not really love her.

Elsewhere, Tsuwabuki tests his new theory that he might be into men, by hugging his work buddies and seeing what happens. Just as he’s driving them nuts with his behaviour, the Emperor’s brother-in-law Shikibu-kyo no Miya appears and offers to teach Tsuwabuki about the joys of loving men, causing him to run off in a panic.

One evening, when Umetsubo is visiting her father Kakumitsu (remember that Shi no Hime is another of his daughters), Tsuwabuki suddenly appears and wants to see Sara. While Sara goes to deal with him, Umetsubo insinuates that Sara might not treat Shi no Hime “like a husband should”, eliciting a VERY defensive response. Sara and Tsuwabuki have a rowdy drinking session together, and when Tsuwabuki wakes up after passing out, Sara has already left for night watch duty. Tsuwabuki pathetically sniffs Sara’s coat until he hears someone playing the koto – Shi no Hime, the woman he coveted for so long! After hearing her recite an oddly sad poem for a happy newlywed, he decides to go and introduce himself… the only way he knows how.

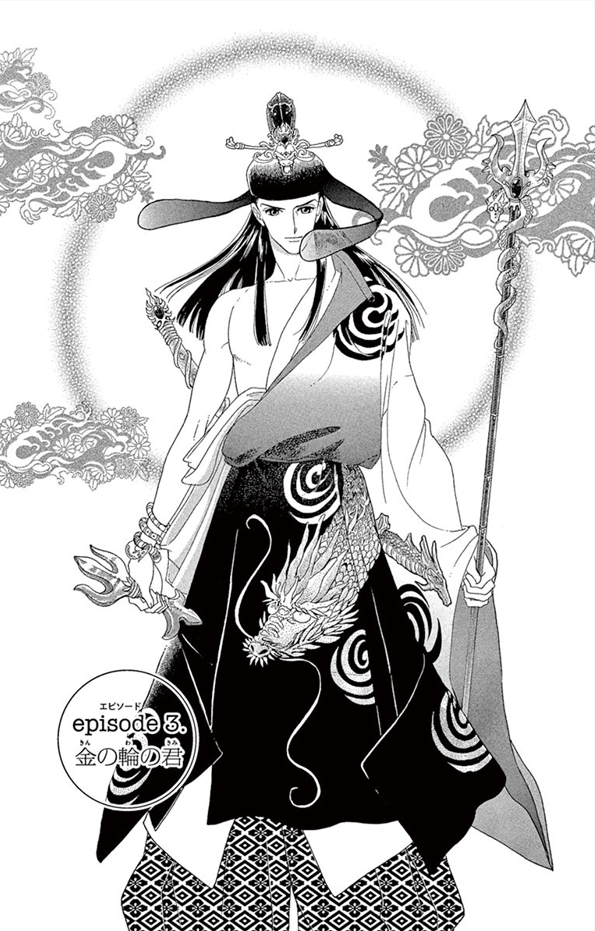

Title page of Episode 10 from volume 2, page 149.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

This is the final chapter of the second volume, giving us a cliffhanger just as things really start going wrong. Tsuwabuki has recognised that he has feelings for Sara, but still hasn’t quite given up on trying to explain them away, with worse and worse results.

The thing I want to take a closer look at today is the chapter’s title page. I mentioned in an earlier post that the Episode 3 title page has some interesting details, portraying the then-Togu dressed like a Buddhist deity. There are many other wonderful title pages, showing off the major characters in a variety of flashy and often meaningful outfits. They’re often good examples of how Saito embeds symbolic details in the artwork, as I discussed a couple of weeks ago.

The title page this time shows Tsuwabuki, looking sad and thoughtful as he holds a coat (or an outer robe, but there aren’t always great equivalent terms for all the items of clothing they wear) close to himself. There are some decorative wisteria flowers in the background, and the coat he’s holding has a wisteria motif too. The image of Tsuwabuki holding the coat evokes the scene later in the chapter when he finds that Sara has left his coat as a blanket for him, while the flowers give us some sense of when this is taking place.

At first, I thought it was Sara’s coat in this image, but then I realised the pattern was different. I was happy enough at that point to say that the wisteria pattern just matched the flowers in the background, until I went through the chapter once again. In the scene when Tsuwabuki awkwardly hugs his friends, several men are taking wisteria branches to put in their caps, and Shikibu-kyo no Miya gives one to Tsuwabuki, lamenting that he no longer decorates himself with his trademark tsuwabuki flowers. And on top of that – when Shikibu-kyo no Miya appears, he is wearing the coat from the title page.

This adds more complexity to the coat situation, as if it weren’t bad enough already (Tsuwabuki even puts Sara’s coat on, so he’s trying it on with Shi no Hime in her husband’s clothes*). Now, the title page isn’t just a nice brooding picture of Tsuwabuki with a reference to the scene with Sara’s coat. By replacing the garment with Shikibu-kyo no Miya’s coat, it ties that scene to the worries Tsuwabuki has elsewhere in this chapter about his own sexual/romantic preferences.

And besides the significance of this particular image in this particular chapter, it’s good just to keep in mind (again) that for the translation, the visuals matter as well as the text!

*his other sins in this chapter include watching Shi no Hime through some blinds – just like he did with Suiren – and then introducing himself using the exact same words (“I am the Chancellor Colonel” – 宰相の中将にございます) as he did with Suiren…………

Thoughts from Episode 9: fellas,

Until now, there have been more than a few moments to make readers wonder who exactly Tsuwabuki is infatuated with, and in this chapter, the penny finally drops for him too.

Until now, there have been more than a few moments to make readers wonder who exactly Tsuwabuki is infatuated with, and in this chapter, the penny finally drops for him too. Following on from last time, Suiren has realised somebody is watching her from behind the blinds. As Tsuwabuki tries to woo her, she stalls for time by making him explain what he means by “love”. Suiren then wonders why his description aligns so well with her own feelings towards Togu – while Tsuwabuki wonders why he isn’t more excited to be meeting his supposed “ideal woman”. He gets impatient with Suiren and himself and tries to rush in (as is his wont) but Suiren fights back and he runs off with his tail between his legs.

Later, the Emperor sees the plum blossoms in Umetsubo’s quarters and immediately throws a party! Sara learns that Tsuwabuki has been moping, Umetsubo briefly stirs the pot, and Sara then goes to speak to Tsuwabuki while everyone is chasing after a butterfly. After a moment of panic when he finds out that Tsuwabuki tried it on with Suiren, Sara attempts to reassure his colleague that he’s still cool and manly even after being rejected. Tsuwabuki then lets slip that he finds Sara more attractive that Suiren (!) and when the butterfly lands on Sara’s cap shortly afterwards, the young guys’ hands touch (!!) and Tsuwabuki blushes (!!!). In the end, Tsuwabuki is left questioning whether his feelings are really for Suiren or for Sara.

Something that Saito does a lot in Torikae baya is setting up parallels between different characters or situations: for example, Episode 7 compares Sara’s first meeting with Shi no Hime and Suiren’s first meeting with Togu, and ends with both siblings nervously thinking about “sleeping in the same bed” (同じ御帳台に寝る). And then in the current chapter, Suiren wonders “Am I… in love with Togu-sama!?” (東宮さまに恋していたのか⁉私は) while Tsuwabuki asks himself “Am I not in love… with this woman?” (恋してない―のか?自分は).

Along those lines, I’ll talk a little bit today about a couple of techniques where one thing is mapped onto another – one of these uses furigana and the other is in the art itself.

First, when Suiren realises that the mystery man behind the blinds is Tsuwabuki, she has a brief flashback to when Sara was telling her about him, and then this happens:

In the present, TSUWABUKI can still be seen through the blinds, one hand raised.SUIREN [thinking] The man who desires me…

SUIREN pictures the TENGU caressing a scared young SUIREN’s face.

SUIREN [thinking] A man.

Looking across the room, SUIREN shouts out in fear.

SUIREN [thinking] The tengu!!

Suiren’s second line here is originally 男, with おとこ written to the side as furigana – straightforward so far. The third line is 天狗…!! but rather than being written with the furigana てんぐ, this is also glossed as おとこ. Techniques like this are used pretty often in manga, allowing the writer to do things like providing quick translations/explanations of unusual or strangely written words, or suggesting multiple meanings at once, like Saito does here. Mapping the sound of “otoko” onto the kanji for “tengu” lets her convey both ideas at the same time.

In this case, all we need is a one-word line and an image of the tengu from Episode 1 to understand that Suiren’s worries about men are closely linked to her and Sara’s childhood experience of being kidnapped. For her, any man could potentially be a tengu, and therefore a serious threat.

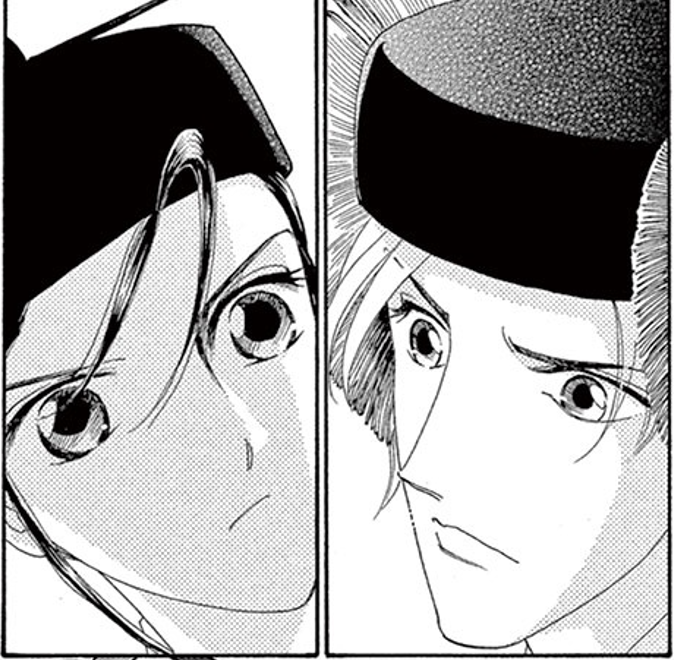

Panel from volume 2, page 142.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

The other example of mapping one thing onto another comes later in the chapter. Tsuwabuki has just admitted that he thinks his work buddy is prettier than his work buddy’s famously beautiful sister and then tellingly asked himself “Was that a weird thing to say?” (おれ今 変なこと言わなかったか?). He says he used to imagine Suiren’s appearance when looking at Sara, and then looks at Sara while picturing Suiren’s face alongside.

On the one hand, this highlights how similar Sara and Suiren are in appearance. On the other, it gives us a sense of what Tsuwabuki has been seeing all along, and how, now that he’s seen Suiren too, this has taken on new meaning for him. The moment where we see Sara and Suiren as if they were one person acts as a turning point in this plotline. It’s right after this that Tsuwabuki begins to question the true nature of his own feelings.

Maybe all those times he told his colleague “your sister must be smoking hot if she looks just like you”, it wasn’t reeeeeally about the sister…

Thoughts from Episode 8: Exit, pursued by a tengu

Episode 8 picks up right where we left off, with Sara and Shi no Hime in bed together... just lying there awkwardly. Sara recalls a drinking party where Tsuwabuki taught him about the birds and the bees, but sees no way to put that into practice, so instead, he holds Shi no Hime’s hand the whole night.

Episode 8 picks up right where we left off, with Sara and Shi no Hime in bed together... just lying there awkwardly. Sara recalls a drinking party where Tsuwabuki taught him about the birds and the bees, but sees no way to put that into practice, so instead, he holds Shi no Hime’s hand the whole night. In the morning, we see some signs that the newlyweds might actually get along.

In the Nashitsubo pavilion, Togu reads until she falls asleep, and Suiren ends up having to also lie awkwardly next to her. When Togu wakes up, Suiren leaves, deeply embarrassed. Later on, Suiren and another attendant are told that Togu won’t be needed for the day’s activities, even though she’s been working hard to prepare. Suiren overhears some sneering officials mocking Togu, but chooses not to reveal the whole truth to her. As it turns out, though, Togu is well aware of the men’s attitudes and has quite complex thoughts about her position in the palace. She appreciates that Suiren avoided making a scene, inspiring Suiren to do all she can to help her.

Finally, Tsuwabuki is in a bad mood. We hear from his buddies that he’s been struggling ever since his best friend married the woman he’d been lusting after. Suddenly, wanting to deal with his confused feelings, Tsuwabuki goes to pay Suiren an uninvited visit – and that’s where the chapter ends.

Today, I’d like to talk a bit about one of the practical aspects of my translation. For a few reasons, I’m formatting it like a script: in the margin is an indication of the speaker, and that’s followed by their lines of dialogue, one speech balloon at a time. I fit the various other text in too, like titles, narration and sound (or not sound) effects.

But that’s not necessarily enough to give the reader a sense of which translated line corresponds to which bit of text. And it’s definitely not enough for a reader who can’t constantly cross-reference with the manga page. My solution for this is image descriptions! In between the dialogue and other text are brief descriptions of what’s going on visually, a bit like stage directions, to provide context.

This is something I’ve been doing since the very start, but I wanted to bring it up now because there are a couple of good examples. I’ll share a humorous one, from when Sara remembers hanging out with Tsuwabuki and his friends:

Panels from volume 2, page 82.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

TSUWABUKI smiles confidently.

TSUWABUKI It's all about having your way with her.

SARA remains confused, while TSUWABUKI smugly continues.

SARA What do you mean, "having my way"?

TSUWABUKI Well, you see...

We see TSUWABUKI provide SARA with an unspecified explanation. They are surrounded by pairs of anthropomorphic rabbit silhouettes in various suggestive positions and upper- and lower-case “A”s. SARA looks scandalised; the tails on his cap are sticking up like rabbit ears, and arrows poke out from his back in random directions.

This was a fun bit to try and describe! I think it’s also a good example of why the descriptions are useful to have. Without some sense of what’s going on visually, the scene would be A) confusing and B) not funny.

At the end of the chapter, there’s also a more serious example, where Tsuwabuki’s visit to Suiren is shown in a two-page spread with no dialogue. That means that the description is the only indication that anything is even happening on those pages. And in other chapters, there have been details in panels that I might have overlooked if I hadn’t been thinking about how to describe them – like flowers associated with particular characters, for example.

Manga is a visual medium. Just like the narration in a novel, the visuals in manga are a fundamental part of how it conveys meaning. Images don’t really need to be translated, so dialogue and other text is always going to be the focus in a translation (I’ve never had to write image descriptions for a manga translation before!) but in one way or another, the visuals do have an impact on the translation. And these odd little stage directions are one way I’ve chosen to reflect that!

Thoughts from Episode 7: Sara meets Shi no Hime, Suiren meets Togu

This chapter revolves around the implementation of decisions made last time: Sara goes ahead with his marriage to Shi no Hime and Suiren goes to court to work for the new Togu. At the end of Episode 6, we find out that Shi no Hime isn’t happy to marry somebody as low-ranking as Sara (not that he knows anything about it), and so as he initiates the proceedings by visiting her for three consecutive nights in this chapter, he faces an uphill struggle.

This chapter revolves around the implementation of decisions made last time: Sara goes ahead with his marriage to Shi no Hime and Suiren goes to court to work for the new Togu. At the end of Episode 6, we find out that Shi no Hime isn’t happy to marry somebody as low-ranking as Sara (not that he knows anything about it), and so as he initiates the proceedings by visiting her for three consecutive nights in this chapter, he faces an uphill struggle.

On the first night, Shi no Hime remains silent in her bedchamber (御帳台) and has an attendant meet him to deliver a letter saying she is ill; determined to succeed, Sara sleeps on the floor. The next night, Sara’s attempts to speak to her finally get a response, but it’s an angry one. On the third and final night, after everyone thinks he’s given up, Sara takes a leaf out of Tsuwabuki’s book and barges in on her in her bedchamber. He finds out that she blames a scar on her forehead for the fact that she won’t be marrying the Emperor after all, and tries to convey some sympathy. In the end, Sara thinks he has to sleep on the floor again, until Shi no Hime snappily implies he should join her.

Meanwhile, Suiren arrives at the palace, scared out of her wits by the throngs of people, and meets the adorable Togu. As it turns out, Togu is a nerd who immediately starts gossiping with Suiren about The Tale of Genji, and when she learns that Suiren also writes, she insists on reading her work – to Suiren’s clear embarrassment. Things go so well that at the end of an evening of reading, Togu won’t let Suiren leave, and invites her to sleep over in her own bedchamber.

Sara bowing outside Shi no Hime’s bedchamber.

Panel from volume 2, page 46. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

Before anything else, I’ll briefly address the use of “bedchamber”. The buildings in the palace are laid out in the shinden-zukuri style, which has presented a few difficulties in translation – ones I’m not sure I’ve adequately resolved yet! Mostly this has involved which things I should describe as verandas, hallways, corridors, etc... but this time the issue is with where people sleep. Rather than a modern bed in a modern bedroom, the michodai (御帳台) is a raised platform surrounded by curtains in a larger room. The challenge here is that it’s still fairly spacious and is totally closed off, making it somewhere in between a big bed and a small bedroom. Also, looking at the situations we’re seeing so far, I don’t think it’s always accurate to describe them as characters literally getting into each other’s beds – so at this stage at least, I’ve settled for “bedchamber”.

Of course, what I really want to talk about today is the fact that this is the chapter where Suetsumuhana is mentioned! When Togu and Suiren first meet, Togu asks Suiren for her favourite female character in The Tale of Genji. Suiren pauses and answers “Suetsumuhana”, and Togu says she agrees.

As I briefly mention here, this character doesn’t stand out for her beauty and talents. The name we know her as refers to the safflower, which is traditionally used to make red dye. Genji, the story’s lustful protagonist, compares her to the flower in a poem, alluding to her big red nose. Apart from her unfortunate appearance, Suetsumuhana is also remembered for living in a dilapidated mansion, being difficult to deal with and having old-fashioned tastes.

So I thought it was fascinating that Suiren and Togu both agree that she’s the best girl in The Tale of Genji! It’s only one passing mention, but it says something about the two characters. Both are shy and reclusive, and they both feel out-of-place in their current positions: Suiren, who was first introduced as Marumitsu’s baby son, doesn’t think she’s cut out for working at the palace as a naishi no kami, while it’s public knowledge that Togu is only in her role – usually given to a male heir of the Emperor – as a stopgap measure. It makes some sense that they might relate to a literary character who is clearly not the ideal woman.

And then I decided to use that as my handle just as a fun reference! Incidentally, the avatar is another reference, this time to Takahata Isao’s film Only Yesterday (おもひでぽろぽろ), where safflower-picking plays a big part.

Thoughts from Episode 6: New year, new ranks!

I’m back from my break, and I’ve been making some more progress with the translation! We left off last time at the end of the first volume, so now let’s move on to Episode 6: The New Emperor.

I’m back from my break, and I’ve been making some more progress with the translation! We left off last time at the end of the first volume, so now let’s move on to Episode 6: The New Emperor.

As that title suggests, this chapter opens with a range of characters gaining new roles at court. The poorly old Emperor has stepped aside in favour of his younger brother, and there are promotions for Marumitsu, Sara and Tsuwabuki. Kakumitsu misses out on a promotion, and he’s more eager than ever to make Sara his son-in-law. Meanwhile, the former Emperor is worried about his young daughter, who has now taken over as Togu (crown prince). He suggests that Suiren become her naishi no kami (a close attendant), leaving Marumitsu with two tricky requests to handle...

At first, Sara and Suiren both refuse. But soon, Sara realises that the only way to counter Umetsubo’s suspicions about him is to agree to marry Kakumitsu’s daughter Shi no Hime. Tsuwabuki is distraught about this because of his existing feelings for Sara Shi no Hime. He calls off his and Sara’s friendship – unless Sara helps him marry Suiren. Then, to deal with this new mess, Suiren agrees to go and work for Togu.

There’s a lot going on here! With the new Emperor crowned – he remains Emperor for the rest of the story – it reframes the first volume as a bit of a preamble. It’s now that characters move into their longer-term roles, and it’s now that Sara and Suiren’s problems really start to rack up.

What I’d like to focus on today is something I talked about back at the beginning: the various ranks and titles the characters hold. This time around, several of them change ranks/titles, and that changes how people refer to them. To summarise:

· The Emperor (帝) is now Emperor Emeritus (上皇) or Suzakuin (朱雀院)

· The Crown Prince or Togu (東宮) is now the Emperor (帝)

· The former Emperor’s daughter (referred to briefly as 女一の宮, “girl first-born prince”) is now Togu (東宮, also 女東宮, “girl crown prince”) and is nicknamed Nanten no Togu (南天の東宮)

· Old man Fujiwara, the one-time Chief Advisor to the Emperor (関白) has retired and entered the priesthood

· His son Marumitsu, formerly a Provisional Upper Councillor of Court (権大納言), is now both Chief Advisor to the Emperor (関白) and Chancellor (左大臣)

· His son Sara, formerly a fifth-rank Chamberlain (五位の侍従), is now a third-rank colonel of the Imperial Guards (近衛府の三位の中将)

· Tsuwabuki, already a colonel, is now also a councillor (中将)

· and Suiren is being offered a position as the new Togu’s naishi no kami (尚侍)

Many of these have been translated in multiple ways before in Willig’s two versions of Torikaebaya monogatari. I won’t necessarily use the same translations as Willig, but I want to be internally consistent at least. The tricky part, as I mentioned in that earlier post, is knowing when to come up with an English version and when to just transliterate.

So far, Togu is still Togu – this is partly to ensure that as in the original, the same term is used whoever holds the position. In my earlier notes, I had it as “Crown Prince”, even after Suzakuin’s daughter takes on the role. I think this does chime pretty well with the manga’s themes, so there’s still the possibility I’ll go back to this later, but we’ll see.

Elsewhere, some roles are translated, but I’ve opted for a transliteration when they’re used as a term of address, such as Marumitsu’s new dual role “Kanpaku Sadaijin”. On the other hand, I’m undecided about naishi no kami. Willig – and others – translated this as “Maid of Honour”, and maybe that’s what I’ll go with too, but I’m unsure. I don’t exactly have great alternatives either, so for the time being, it’ll continue to be naishi no kami, just transliterated.

It's lucky that a lot of these characters do also have nicknames so that we don’t have to refer to them only by their job titles the way the original Torikaebaya monogatari did. Other modern versions do this too – Willig’s published version (The Changelings) sort of does it as well – and for the sake of my sanity, I’m relieved that Saito followed in their footsteps!

Thoughts from Episode 5: Names, names, names

This week’s chapter revolves around a hunting trip organised by the Emperor. The most important people at the court go and have a good time in the outskirts of Heian-kyo, and the citizens get an opportunity to see them in their finery. You probably won’t be surprised to hear that the stars of the event are to be Sara and Tsuwabuki!

This week’s chapter revolves around a hunting trip organised by the Emperor. The most important people at the court go and have a good time in the outskirts of Heian-kyo (around here), and the citizens get an opportunity to see them in their finery. You probably won’t be surprised to hear that the stars of the event are to be Sara and Tsuwabuki!

But before the excursion, somebody comes and bothers Sara. This person is an unnamed woman who once worked for Suiren’s mother and now works for the jealous Lady Umetsubo. The woman learns that Sara takes a few days’ break every month and reports this back to Umetsubo, who quickly concludes that this is due to tsuki no sawari – menstruation. As ridiculous as her own attendants find this idea, Umetsubo becomes certain that Marumitsu has two daughters and has forcibly raised one to be a man.

On the hunting trip, Sara races into an early lead, causing Tsuwabuki to leave in a huff. Suddenly, a mysterious man (who we’ve just seen having a chat with Umetsubo!) starts firing arrows at Sara. Sara hurries back, and after an arrow narrowly misses the Emperor, a search party goes looking for the would-be assassin. But Togu sees that Sara was injured by an arrow, and Umetsubo of all people steps in to give him first aid. This is obviously a ploy to publicly expose Sara literally and figuratively. Just in the nick of time, Tsuwabuki returns and Sara makes an excuse to leave with his help.

The whole incident raises Sara’s profile even more, so Umetsubo changes her strategy. She tells her father Kakumitsu to do something she was previously so keen to avoid – arrange for Sara to marry Kakumitsu’s youngest daughter...

One aspect that’s been a bit challenging in the past few chapters has been characters’ names. In earlier posts, I talked about court ranks and briefly introduced some of the major characters. Something I mentioned previously is that they’re not always referred to in the same way (and in the original Torikaebaya monogatari, they don’t even get personal names) and this has already presented some difficulties.

For example, when somebody is addressed by their position, what should it be in my translation? So far I have gondainagon – Marumitsu’s title – as “Provisional Upper Councillor of State” (“provisional” and “of state” sometimes omitted), but I’m not sure this always works so well when he’s addressed directly. Similarly, I mostly keep the Crown Prince as Togu (東宮), mainly because this title will soon be inherited by the current Emperor’s daughter. However, I do find it necessary sometimes to say “Crown Prince” – like when he’s specifically listed alongside the Emperor, or even just for the sake of reminding the reader what a togu is. Maybe there’s an argument for referring to the Emperor as “Mikado” instead for consistency?

The other area where this has proven tricky is with characters whose names are said slightly differently in different contexts. Sarasoju no Kimi (沙羅双樹の君) is often just Sarasoju, but sometimes Sarasoju no Jiju (沙羅双樹の侍従). It gets shortened to Sara, or Soju if Tsuwabuki is speaking. These are generally fine, because we hear about Sara so often that if I just keep it as-is (or translate Sarasoju no Jiju to “Chamberlain Sarasoju”) it won’t actually be hard to follow.

But what about characters who rarely appear? Marumitsu’s wives are first introduced as Nishi no Ue (西の上) and Higashi no Ue (東の上). These “names” are literally just “west” and “east” plus an honorific. I was happy enough to transliterate them to begin with, but now that Umetsubo and her nosy attendant are talking about them, they say “kata” (方) instead of “ue”. This is still an honorific, but it isn’t the same one, so that complicates my earlier decision to call them Nishi no Ue and Higashi no Ue in the translation. In all likelihood, I’ll just go back and change them to Nishi and Higashi, but I’ll have to think about it a bit longer!

And with that, we’ve reached the end of the first volume! In some ways it’s been quite representative of the series as a whole – hitting the main story beats of Torikaebaya monogatari but with some added drama, angst and action – but in one big way, it isn’t. And that’s because volume 2 starts off with a big reshuffle where various characters get the job titles that they’ll hold for most of the story beyond that point. So basically, forget everything I just said about what everyone is called! T_T

There’s going to be a bit of a break before my next blog post on here. I’m going away for most of April, and unless there’s some big development during that time that I want to report on immediately, I doubt I’ll have a chance to write a post until I get back. So that’s probably it from me until next month! 👋

Thoughts from Episode 4: Religion in Torikae baya

This week’s chapter introduces a major new character and reveals some more about something that we got a touch of last time: organised religion at the court.

Episode 4 begins shortly after the eclipse incident, with Tsuwabuki increasingly sticking his nose into Sara’s business. According to Tsuwabuki, and reportedly others in the palace, Sara isn’t as amorous as a real young man at court should be. Tsuwabuki and his usual two buddies try to teach Sara about romance and how to seek it most efficiently, all of which sounds like a huge hassle to Sara. Especially annoying for Sara is Tsuwabuki’s continued insistence on getting to meet Suiren. It all results in Sara feeling quite forlorn about his place in the world.

This week’s chapter introduces a major new character and reveals some more about something that we got a touch of last time: organised religion at the court.

Episode 4 begins shortly after the eclipse incident, with Tsuwabuki increasingly sticking his nose into Sara’s business. According to Tsuwabuki, and reportedly others in the palace, Sara isn’t as amorous as a real young man at court should be. Tsuwabuki and his usual two buddies try to teach Sara about romance and how to seek it most efficiently, all of which sounds like a huge hassle to Sara. Especially annoying for Sara is Tsuwabuki’s continued insistence on getting to meet Suiren. It all results in Sara feeling quite forlorn about his place in the world.

Meanwhile, we meet Lady Reikeiden, the Emperor’s consort, and Lady Umetsubo, the Crown Prince’s consort. They’re also Kakumitsu’s two eldest daughters, making them Sara and Suiren’s cousins. Umetsubo is mad with jealousy over her father’s interest in the pair, and is convinced that there’s something fishy about them. Finally, she learns from a former employee at Marumitsu’s home that Sara’s mother supposedly had a baby girl while Suiren’s mother had a baby boy. This isn’t enough for Umetsubo to figure everything out, but she’s suspicious – and she’s not happy about it.

Dainichi Nyorai.

Cropped panel from volume 1, page 131. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

In this story, we hear a lot about fate, and particularly how people’s misfortunes are the consequence of their previous lives. This is the most obvious link to Buddhist ideas, but religion shows up regularly in lots of other forms too. Episodes 3 and 4 have introduced quite a few of these.

Last time, I mentioned the men from the on’yoryo. They introduce themselves as the Masters of Astronomy (天文博士), Chronometry (歴博士) and Divination (陰陽博士). These guys are experts in strands of what we call onmyodo, covering various forms of divination based on yin and yang, the elements, the movements of celestial bodies, etc. I think of these three as somewhere between scientists, priests, magicians and (this being the Heian court) bureaucrats. They don’t play a huge role in the story, but they provide a little taste of the varied belief systems involved in court life.

Another detail in Episode 3 was a crystal ball, which the Emperor says he once stole from his younger brother Togu. The crystal ball contains an image of Kundali, a fearsome deity with many arms holding various religious implements and wrapped in snakes. The title page for the chapter shows Togu dressed like Kundali and holding the same items: a vajra (thunderbolt) and a trisula (trident). Elements like these can be very useful for me as the translator, as some of them can be distinctive features of a particular deity, helping me figure out exactly what I’m looking at and why that matters. As one of the Five Wisdom Kings, Kundali is an originally Hindu deity with the power to repel evil, and when Togu faces the eclipse with this crystal in hand, he too displays that power.

So what sort of Buddhism are we looking at? The sects that really took off during the Heian period were Tendai and Shingon, but can we get more specific? A scene in Episode 4 gives us a bit more information on this front. When Tsuwabuki is giving Sara tips on being more manly, he suggests that temples are good places to meet people, because esoteric teachings (mikkyo 密教) are popular with the nobility. They attend a sermon, where we see a statue that appears to be of Vairocana (Dainichi Nyorai), a central buddha in esoteric sects – handily (heh) recognisable by the position of his hands.

Tsuwabuki also claims that listening to these sermons is a great way to pick up chicks – which sounds a lot more plausible when the priest starts talking about “entering a state of ecstasy through sexual intercourse between man and woman” (男と女が性の交わりによって恍惚境に入ること). It sounds like this comes from the Rishukyo (理趣経), an important scripture in Shingon, which draws from Tantric Buddhism, or Vajrayana. That’s the same “vajra” as the thunderbolt held by Kundali/Togu in the previous chapter, by the way. Overall, I’m inclined to think that the focus on these more mystical-sounding ideas is pointing towards Shingon being the fashionable branch of Buddhism in Torikae baya. There are some other details that might help pinpoint it even more closely, but I’m no expert, so at least for now, that’s as definitive as I’m willing to get!

Thoughts from Episode 3: The Eclipse

After Episode 2 showed Sara starting his exciting new job working for the Emperor and meeting his new best friend (whether he likes it or not) Tsuwabuki, this chapter gets a bit more dramatic. Tsuwabuki shows up uninvited at Sara’s home with two of his friends, and gets terribly upset that Sara won’t introduce him to Suiren. As it turns out, everybody has heard about Suiren, even the Emperor! This causes Sara to have (apparently for the first time in a while) a nightmare about the tengu from Episode 1. The tengu tells Sara that he and Suiren are cursed, and that the curse will be lifted when the tengu devours the Emperor.

After Episode 2 showed Sara starting his exciting new job working for the Emperor and meeting his new best friend (whether he likes it or not) Tsuwabuki, this chapter gets a bit more dramatic. Tsuwabuki shows up uninvited at Sara’s home with two of his friends, and gets terribly upset that Sara won’t introduce him to Suiren. As it turns out, everybody has heard about Suiren, even the Emperor! This causes Sara to have (apparently for the first time in a while) a nightmare about the tengu from Episode 1. The tengu tells Sara that he and Suiren are cursed, and that the curse will be lifted when the tengu devours the Emperor.

Three important men then show up from the on’yoryo (for now at least, I have this as the Bureau of Yin and Yang – this is where they practised divination, astrology, etc) to reveal that an annular eclipse is coming, and the Emperor immediately falls ill. While everyone in the palace prepares to hide him away from the ominous effects of the eclipse, the Emperor gives his younger brother (Togu, the crown prince) a crystal ball containing an image of Kundali, one of the Five Wisdom Kings. Sara, inspired by another vision of the tengu, decides to risk being cursed by the eclipse in order to break his own curse, and is soon joined by Tsuwabuki and Togu. They go to the roof of a high building, where Togu holds out the crystal ball and prays for rain. Clouds come and obscure the eclipse, and the Emperor recovers.

Title page of Episode 3 from volume 1, page 83. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

There are plenty of things to think about in this chapter! There’s new information about the tengu’s curse and how that ties into other aspects of the story, as well as plenty of details about the belief system at the court. Today, though, I’ll just take a look at the chapter’s title – which is quite enough to handle!

Episode 3 is titled 「金の輪の君」 (kin no wa no kimi). This is quite a bit more abstract than previous titles, which were just characters’ names. The meaning of “kin no wa” becomes clear when characters begin talking about the eclipse. The astrologers talk about a 金の環の日食 (kin no wa no nisshoku), referring to the annular eclipse. Usually this is written without the のs, as 金環日食 (kinkan nisshoku), but it’s same in practice, qualifying the eclipse (nisshoku) as one where a golden ring (kin no wa) is visible.

You might notice – not that I did at first! – that the spelling in the dialogue uses the kanji 環 where the title uses 輪. I was trying to figure out what difference this would make and why it would be worth writing it two ways, but I think it’s most likely for practical reasons. In the title, it’s standing alone, and as 輪 is more commonly used for “ring” as a noun, it makes a bit more sense in that context. On the other hand, when it appears again later, it’s in the full “annular eclipse” phrase. It uses the same words, and with the same meaning, but “kinkan nisshoku”, the usual term for an annular eclipse, uses the more abstract 環 and can’t be written with a 輪. Perhaps there is more to it, but that’s the only reason I can see for writing it two different ways.

Another side point here is about the word for eclipse itself: 日食, meaning that the sun is eaten. There are old Chinese myths about monsters eating the sun during an eclipse, including a black dog called the tiangou. This is written as 天狗, the same spelling as “tengu”, which in Japan came to be seen as birdlike monsters such as the ones we see pretty regularly in Torikae baya. So when the dream-tengu tells Sara it’s going to devour the Emperor – whom the people at the court handily point out is symbolised by the sun – it connects closely with old myths about eclipses.

Anyway, what about that title? How should it be translated? As we have the “kin no wa” but not the “nisshoku”, it doesn’t really seem right to translate this as “eclipse”. That would be providing information that the Japanese readers aren’t getting at this point. “Annulus” could make sense as that’s the part that is mentioned, but the fact it’s written as 金の輪 and not 金環 puts me off that too. And there’s a later line that makes me feel that it could be intended to evoke the idea of a halo as well, which then gels with the imagery of the title page. This all makes me lean towards a fairly literal answer, so that I’m not saying more than I should, and so that it remains mysterious. In the end, I came up with “He of the Golden Ring” – interpreting the “kimi” in the same way as it gets used as a term of respect in people’s (usually men’s) names.

I’m just glad not every translation choice is as complicated as this!

Thoughts from Episode 2: Beauties and Cuties

This week’s post looks at the second chapter of Torikae baya, and some thoughts about aesthetics and vocabulary choices.

Episode 2 opens with Sara and Suiren at the age of 14, going through their genpuku and mogi ceremonies respectively – in the afterword of volume 3, Saito points out that these specifically gendered rites are the predecessors of the modern-day Seijin no Hi.

This week’s post looks at the second chapter of Torikae baya, and some thoughts about aesthetics and vocabulary choices.

Episode 2 opens with Sara and Suiren at the age of 14, going through their genpuku and mogi ceremonies respectively – in the afterword of volume 3, Saito points out that these specifically gendered rites are the predecessors of the modern-day Seijin no Hi. These are attended by Marumitsu’s slightly more angular brother Kakumitsu, and the brothers’ father, who doesn’t have a catchy individual name, so I’ve been calling him Fujiwara Senior in the translation so far (and Jijimitsu in my head!). Kakumitsu and Fujiwara are both clueless about Sara and Suiren’s secret, with Kakumitsu musing that Sara would make a great son-in-law and Fujiwara believing that Suiren’s beauty will catch the eye of even the Emperor. We also learn around this point that Sara and Suiren have even more names, with Marumitsu saying that Sara will “borrow” the name of Fujiwara no Tsukimitsu from Suiren and “lend” Suiren the name Suzushiko.

Next, Sara goes for his first day at work. The Emperor is so impressed that he immediately gives Sara a new job as his chamberlain (侍従). Sara begins to worry once he learns that nobody else at court is like him, but otherwise, everything is going well for him at work. On the day of the komahiki ceremony, we’re introduced to Colonel Tsuwabuki, another popular young man at court. When Sara manages to be even more impressive and dashing than him, Tsuwabuki chases him down to announce that the two are now to be best buddies, and that he hears Sara has an identical sister (😉) he’d like to meet.

How to make friends as a young gentleman in the Heian period.

Panels from volume 1, page 76. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

Something that might strike you here is that everyone is beautiful! This is partly down to the art style, but it’s also something that comes up constantly in the dialogue. Old Man Fujiwara compares Suiren’s beauty to the mythical Princess Kaguya; meanwhile, young men like Sara and Tsuwabuki are also regarded as beautiful. I try not to translate 美しい (utsukushii) as “beautiful” every single time, but even if I don’t, the word still comes up a lot.

This reflects the Heian court’s preoccupation with beauty in various forms: aesthetic appeal, but also good taste and manners. We’ll see more examples of what Ivan Morris called the Heian court’s cult of beauty throughout the series, with Sara and the men being accomplished musicians and poets, and Suiren and Nanten no Togu being avid readers. This is what we know mattered to the ruling class, and it’s also what a lot of people today will be expecting from art related to the Heian period. Basically, it’s obvious that everyone should be beautiful in a Heian court romance!

But while I’ve mostly been thinking about 美しい so far, that isn’t the only way that people are described. We see all kinds of different terms, and although most of them seem reasonable enough in a piece of historical fiction, there’s one that seems to stick out: かわいい (kawaii). It’s not as if this is actually too modern, but it feels like it is – especially when it’s repeatedly followed with a little heart symbol. There’s some sense of deliberate anachronism that overrides my instinct to avoid translating it as “cute” in a historical setting. For example:

We see a closeup of SARA, then the reaction of the COURT LADIES.

SARA [thinking] Tsuwabuki no Kimi?

LADY 1 Oh, look! Sarasoju no Kimi is here!

LADY 2 What a cutie! ❤

TSUWABUKI glances at SARA, who is taken by surprise. In the background, the LADIES are still excited.

A LADY [aside] ❤

Obviously, the manga isn’t actually written in classical Japanese, but it’s interesting to see these points that seem to draw attention to the fact that it’s in modern Japanese. Another example that stands out is in the next chapter, when one of Tsuwabuki’s friends uses the obviously post-1990s word 萌える (moeru). I’ll have to write a whole other blog post about “moe” at some point, but what I want to say for now is that this, like the other little anachronistic dialogue moments, serves to make the characters more relatable. A lot of the time, they use archaic expressions or structures that situate them in the past, but when they describe the beauty around them in the same way that a reader might describe the beauty of the manga art, it feels like they aren’t so far away.