Blogging about my Torikae baya manga translation project.

Digression: 2025 wrap-up party

I’ve had a bit too much happening to stick to a regular posting schedule in the last couple of weeks, but I want to fit one last one in before the year is up!

After spending quite a lot of time in the first few years of the PhD making preparations and trying to work things out, I finally managed to focus on the main practical work of the project this year, and I’m happy to have made a lot of progress. So today, I want to go over what’s happened in 2025 and what comes next!

I’ve had a bit too much happening to stick to a regular posting schedule in the last couple of weeks, but I want to fit one last one in before the year is up!

After spending quite a lot of time in the first few years of the PhD making preparations and trying to work things out, I finally managed to focus on the main practical work of the project this year, and I’m happy to have made a lot of progress. So today, I want to go over what’s happened in 2025 and what comes next!

The biggest thing of course was working on translating Torikae baya, one chapter at a time. At the outset of the project, I had visions of a scanlation of all 13 volumes, but this was reined in early on for a few reasons. Because of the impracticality of basing everything around images and the greater potential for copyright issues, I decided to format the translation a bit like a screenplay, in a way that should make it readable both to people who can view the original manga pages alongside and people who can’t. A nice upside of this, which I discussed briefly here, is that the need to describe the images helps me notice details I might’ve missed otherwise and ensures I pay appropriate attention to the visual side of the medium.

Meanwhile, earlier experiments with the style of the translation made it clear that 13 volumesworth (65 chapters) was never going to be even close to fitting into the accepted limits for the thesis, and it would mean spending a lot of time translating large portions that would be unlikely to make the final cut. So the plan was to translate volumes 1 to 7, then skip to 13.

These aren’t just random numbers! I couldn’t pick the exact chapters to include in the thesis proper without actually doing the work of translating them and learning through the process what material would be most relevant. However, I was confident early on that I would want to say a lot about this series as an adaptation of Torikaebaya monogatari, so I chose to focus on translating the portions that follow the original plot most closely – a lot of the manga’s totally new material comes between Sara and Suiren’s return to the capital and the ending. This will still be too much to fit within the word count restrictions for the thesis, so I’ll need to whittle down the 40 translated chapters to somewhere between 15 and 20 that are especially significant, while the rest will probably end up in an appendix.

Another big event this year was my trip to Kyoto in the summer, with funding from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation, the Japan Foundation Endowment Committee and Edinburgh University’s School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures. I studied classical Japanese language, visited locations from Torikae baya along with places like the Kyoto International Manga Museum, and I even got to meet Saito Chiho and ask her questions about the process of writing Torikae baya (I can still hardly believe that really happened!). Altogether, the trip gave me important ideas and insights for the project, and changed how I think about the Japanese language. It was a lot of fun too!

Around the same time as that trip, one exciting development was that I moved from part-time to full-time study. Part of the slowness up to that point came about from being limited in how much time I could devote to working on the project, but fortunately, I got confirmation during the summer that the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation were willing to give me full-time funding. Since September, that has made it realistic for me to increase the pace of my work going into the later stages of the project.

I also had a couple of opportunities this year to present my work, first at the Japan Foundation/BAJS PhD workshop here in Edinburgh in February, then at the BAJS Conference in Cardiff in September. It was great to get experience of giving talks as well as meeting other people working on related and (much more often) very unrelated topics.

And finally, in between all these other activities, I was also writing these blog posts! I’ve found this helpful for getting some of my thoughts in order and briefly exploring topics that could make their way in some form into the commentary section of the thesis. I didn’t particularly plan to do it this way, but I’ve mostly gone one manga chapter at a time. As the translation process has sped up in the last few months, the chapters I write about have increasingly lagged behind the ones I translate. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, because I find it quite useful really to return to something I haven’t touched in a few weeks and go over it with fresh eyes.

Anyway, I’m excited to say that because of that increased work rate on the translation, I actually finished translating the 40 chosen chapters a couple of weeks ago! It’s just a first draft and the job is by no means complete, but this is definitely a huge milestone. It adds up to more than 130,000 words – more than the limit for the whole thesis on its own – and even the blog posts so far come to about 28,000 on top of that.

That means one of the main things to work on in 2026 is narrowing down what exactly is going into the thesis. I’ll be looking closer at the translation to redraft it, examine the key points to concentrate on and pick out the chapters that will go into the thesis proper. There’ll be a lot of reading too, and a lot more blog posts to write to continue working out exactly what’s going into the commentary! I have another conference lined up in a few weeks’ time – I’m participating in a panel at InTO MANGA: Critical Paths in Manga Studies in Torino – and I’m also planning to apply to at least one other conference later in the year.

And with that, the last thing I want to say for this year is THANK YOU to everyone who has supported the project in any way! Please keep on reading as I continue talking about Torikae baya and sharing project updates in 2026. ❤

Digression: Research trip report

Something different this week! I’ve hinted in previous posts that I’ve been on a trip in Japan over the summer, and now that I’m finally back, I want to talk about what happened.

The main purpose of the research trip – which I managed to do with funding from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation, the Japan Foundation Endowment Committee and the School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures at the University of Edinburgh – was to take part in a summer school programme for classical Japanese at Doshisha University in Kyoto. Over six weeks and a bit, I learnt the basics of classical Japanese (kobun) and how to understand texts. While I was there, I also took the chance to visit some of the locations from Torikae baya and – very excitingly!! – I went to Tokyo and spoke to Saito Chiho in person about the manga.

Something different this week! I’ve hinted in previous posts that I’ve been on a trip in Japan over the summer, and now that I’m finally back, I want to talk about what happened.

The main purpose of the research trip – which I managed to do with funding from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation, the Japan Foundation Endowment Committee and the School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures at the University of Edinburgh – was to take part in a summer school programme for classical Japanese at Doshisha University in Kyoto. Over six weeks and a bit, I learnt the basics of classical Japanese (kobun) and how to understand texts. While I was there, I also took the chance to visit some of the locations from Torikae baya and – very excitingly!! – I went to Tokyo and spoke to Saito Chiho in person about the manga.

First, the course. For about three hours each weekday morning, we spent the first week or two going through all the main grammar points in Shirane’s Classical Japanese: A Grammar. It’s a pretty dry book, but there isn’t really any way around reading over and memorising all the conjugations and auxiliary verbs and particles, and I think this textbook handles it all pretty comprehensively! And even though this intensive approach was a lot of hard work and effort, it meant we could fairly quickly move on and start practicing applying what we’d covered by looking at original texts.

Classical Japanese is very different from modern Japanese. A lot of the words resemble ones we know now, but they might behave differently, or have different meanings. Plus, there are words for things that we just don’t have in the modern world. A lot of the conjugation rules in modern Japanese evolved as the sounds or uses of older patterns changed with time, sometimes frustratingly turning into things that look a lot like different older rules (I’m convinced that in whatever form Japanese takes in the future, there will be a whole new set of unrelated structures that all abbreviate to ん). But once you start getting the hang of the old rules, then you can start breaking it all down and trying to understand. And you know, it does actually get easier with practice!

In the last post, I gave an example of a part in Torikae baya that I’ve now been able to retranslate with better understanding of how to approach classical quotations. I’m looking forward to applying this knowledge elsewhere too, to translate poems like these better, but also to take a look at the original text and see for myself where different interpretations come from.

In between studying, buying things to take home and seeing an all-women Castlevania musical, I found time to seek out some of the locations that appear in the manga. The places in Torikae baya are often depicted in very specific detail, and I was keen to see some of them for myself and get a sense of where things are and what they’re like.

I went to Kurama, where Sara and Suiren get kidnapped by the “tengu” bandits in Episode 1. The main attraction is the temple, but if you keep walking up the mountain, you reach an area where gnarled tree roots are exposed above the ground. It’s very striking, and that’s probably why Saito put it in the manga! After Sara and Suiren run away from the gang, this is where Marumitsu finds them sleeping in the morning.

Trees in Kurama.

Marumitsu finds Sara and Suiren.

Panel from volume 1, page 33. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

Conveniently, the university and my accommodation were both near the old Imperial Palace, which is easier to visit than I think it used to be. Buildings here serve as models for their counterparts in Torikae baya, including the Shishinden and the Seiryoden.

The current Shishinden at the Imperial Palace in Kyoto.

The Shishinden as it appears in the manga.

Panel from volume 1, page 116. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

Yoshino is another major location in Torikae baya. I’ve been there a few times before, but always to Yoshinoyama, the mountain itself, so I hadn’t seen it quite as it appears in the manga. By visiting the area around Yume no Wada this time, I understood that the palace they go to must be this one, and that Sara and Suiren’s search for fireflies probably takes them along the Kisadanigawa and up the mountain from the east side, not at all the route that visitors take to Yoshinoyama nowadays. I also happened to go there at about the same time of year as Episode 13 in the manga – I didn’t spot any fireflies, but I suppose they didn’t either in the end!

Part of a notice board at the excavation site of the Miyataki Ruins in Yoshino.

The palace at Yoshino in the manga.

Panel from volume 3, page 80. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

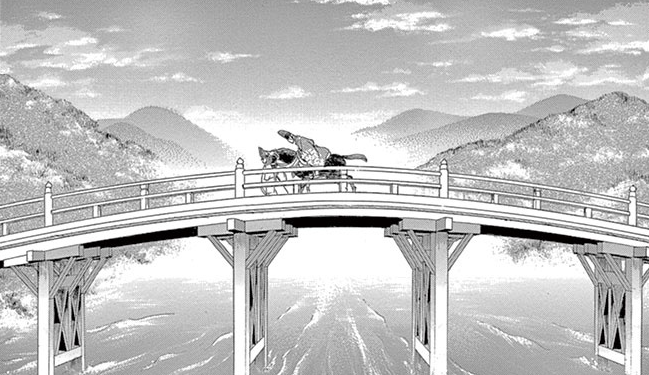

The class took a field trip to Uji, mainly because of its connection to the Tale of Genji, but it is also a location a bit later in Torikae baya, particularly around the Ujibashi, a bridge that has various historical and literary claims to fame (though it has been rebuilt many times and the current one is really quite new). The nearby Tale of Genji Museum also has some useful information about customs and architecture of the Heian period.

The current Ujibashi.

Tsuwabuki crossing the Ujibashi.

Panel from volume 6, page 155. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

Getting to see these places for myself was fun, but informative too! I got a clearer sense of scale and distance, which helped me understand some of the manga scenes better. For example, you get a very strong sense of the danger Sara and Suiren face in Episode 1 when you realise they have to flee uphill to such a remote hiding place on the mountain. There’s no guarantee that their father would find them before the bandits do – if at all.

Besides these specific locations, I also visited places like Torin’in, a temple known for sarasoju flowers, and the Kyoto International Manga Museum. All in all, it was good just to have the chance to stay for an extended period right in the middle of where Torikae baya takes place!

And last but not least, I was lucky enough to get to interview Saito Chiho herself! Though there is a bit of information available about how she approached writing Torikae baya in a few magazine interviews and the afterwords that appear in each manga volume, I was interested to learn more about the process, her sources, etc. During our interview, I heard about how much background research was involved and how she wanted to show the near-constant annual cycle of ceremonies in the Heian court. I got a strong sense that making the story feel more positive (not that everything is exactly happy in the manga, but in contrast with the quite austere and fatalistic Buddhist messaging of the source material) was a key factor in the adjustments she made in the adaptation.

I also got to see her workroom and take a look at the many books that informed the adaptation. Besides different versions of Torikaebaya monogatari, there was a lot about Heian period customs, beliefs and – of course – clothes. Afterwards, I even managed to find copies of a couple of the books she showed me! It was a really exciting opportunity, and I learnt a lot and got plenty of motivation from it too.

And so that’s what I’ve been up to for the past couple of months! It’s been so busy that the main translation work has slowed down a bit, but now that I’m home, I’ll get back on track and hopefully be able to do a better job with everything I’ve learnt since!

Digression: Keeping track of time in Torikae baya

Something I’ve been doing as I’ve worked through the translation is noting indications of the passage of time in Torikae baya. The story takes place over several years, and while some of the jumps forward are made quite clear, there are other subtler indications too, and I want to make sure there’s nothing I’m missing! I’ll say a bit today about how much time has passed in the series so far and what kind of details I’ve looked at, but if you just want the basics, you can also take a look at the new timeline page I put together!

Something I’ve been doing as I’ve worked through the translation is noting indications of the passage of time in Torikae baya. The story takes place over several years, and while some of the jumps forward are made quite clear, there are other subtler indications too, and I want to make sure there’s nothing I’m missing! I’ll say a bit today about how much time has passed in the series so far and what kind of details I’ve looked at, but if you just want the basics, you can also take a look at the new timeline page I put together!

First, when does this take place? The original Torikaebaya monogatari was probably written in the late Heian or early Kamakura period, and the setting for the story is definitely some point in the Heian period. There have been a couple of times where I got into rabbit holes trying to work out exactly when the manga could be set based on things like dates of historical eclipses. I even concluded at one point that it wasn’t chronologically possible, because there are references to Yoshino no Miya having been on a mission to Tang China, but it’s also made clear that The Tale of Genji already exists.

The end result of all this is that I don’t really know! Maybe the Tang reference is just outdated terminology for the time period, or maybe the timing really isn’t intended to be very specific.

But at least on a closer level, we can work out some details about the timeline! Early on, it’s made quite clear how much time passes: the story starts with Sara and Suiren being born, the major kidnapping incident takes place six years later, and the discussions about Fujiwara no Marumitsu’s son taking a job at court begin when the siblings are almost 14 – time for becoming an adult, as far as everyone in this setting is concerned. The next clear indication of characters’ ages comes in Episode 6, when we hear that Shi no Hime – 19 years old – is three years Sara’s senior. Otherwise, we generally have to rely on other clues.

I want to come back to the point about coming of age though. It’s worth noting that Sara and Suiren are pretty young, at least by the standards a lot of us would expect. This also applies to other characters. Tsuwabuki mentions once that he is 18, and soon afterwards he says that Sara is still 16 at that point, so they’re just two years apart. We don’t know Nanten no Togu’s age, but she’s noted as seeming like a child despite her astuteness, so it’s probably fair to assume she isn’t too far away from Sara and Suiren’s age.

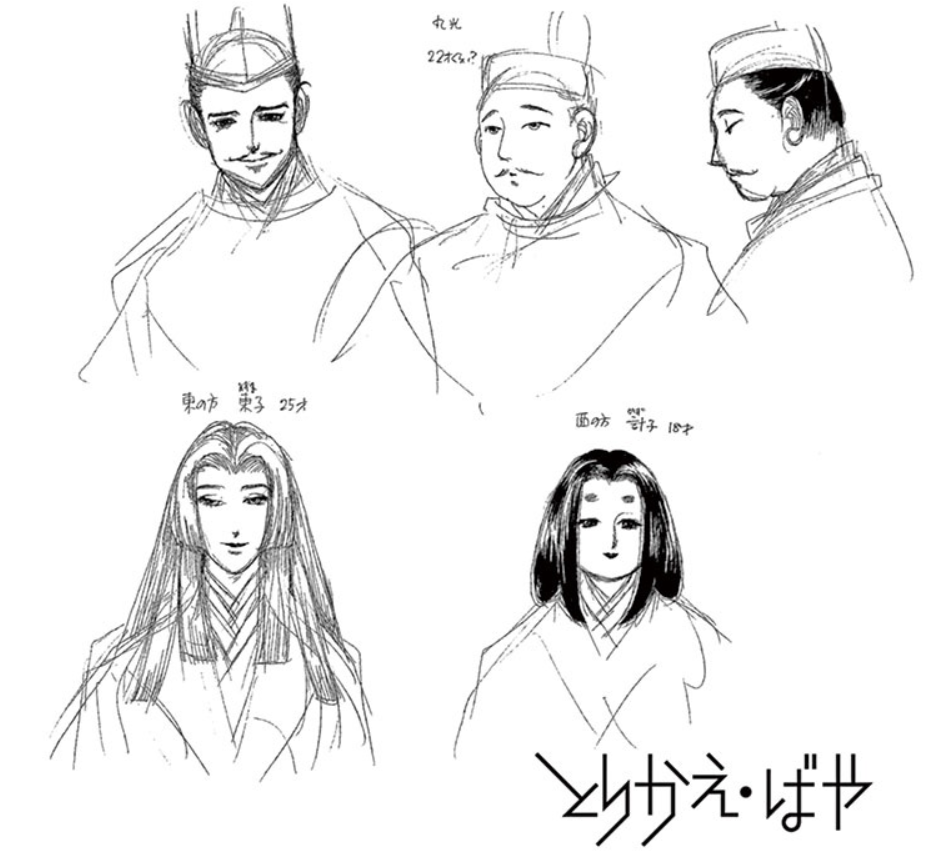

Production sketches of characters from volume 1, page 150.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

There are no in-text references to the age of Sara and Suiren’s parents, but there are some sketches included between chapters in Volume 1 that can help. There’s a sketch of Marumitsu, supposedly around 22 years old, and I think it’s fair to assume that’s as of when the siblings are born. There are also drawings of his wives, with Higashi no Ue (Suiren’s mother) at 25 years old and Nishi no Ue (Sara’s mother) at 18. This aligns quite well with the ages at which Sara and Suiren are entering adult life: if they can start working at 14 and get married at 16, it’s not so bizarre that they’d be having children somewhere around 20.

And as for other signs of the passage of time, we can look at details like seasonal events. The komahiki that takes place in Episode 2 is supposed to have been an August event, so it must be within the first few months of Sara entering the work force. The fact that the changing of the Emperors is specified to take place at New Year also helps set up the chronology of some of what follows.

After that, another thing I found myself looking at obsessively was flowers. Around the time of Sara’s marriage to Shi no Hime and Suiren starting her job as naishi no kami, we know that not much time has passed since New Year, because we see snow and because there’s a plum blossom party at the palace with the appearance of a notably unseasonable butterfly. In the next couple of chapters, there are frequent mentions of the cherry blossoms – showing that spring has come – and even more specific points like how far into the season it is, and the appearance of wisteria which typically comes just after.

I won’t write out everything that I’ve considered with respect to the timeline, but I promise there’s a lot! Again, please do check out the timeline page if you want to get a quick idea of what happens when – and I’ll be keeping it updated too!

Digression: Who’s who in Torikae baya?

Something slightly different this week! So far I’ve been talking about quite a few different characters in Torikae baya, and I’ll be talking about many more in future posts. With that in mind, I want to give a bit of an overview of who makes up the cast of the manga, and who each character’s counterpart is in Torikaebaya monogatari.

Something slightly different this week! So far I’ve been talking about quite a few different characters in Torikae baya, and I’ll be talking about many more in future posts. With that in mind, I want to give a bit of an overview of who makes up the cast of the manga, and who each character’s counterpart is in Torikaebaya monogatari.

First, we have the protagonists, Sarasoju (沙羅双樹) and Suiren (睡蓮). In the manga, each is named after flowers blooming nearby at the time of their birth: sarasoju is the sal tree, which is associated with the death of the Buddha, and suiren is the water lily. Family members tend to abbreviate “Sarasoju” to “Sara”, while his colleague Tsuwabuki calls him “Soju”. In Torikaebaya monogatari, neither sibling has a personal name and both are referred to by their job titles, Sara’s counterpart being a chunagon (中納言) and Suiren’s being a naishi no kami (尚侍) for most of the story.

Their father is Fujiwara no Marumitsu (藤原丸光). As in Torikaebaya monogatari, the father begins the story as a gondainagon (権大納言), with a brother (Kakumitsu, 角光, in the manga) who is the udaijin (右大臣). Fitting these names, Saito draws Marumitsu with rounder features and Kakumitsu with sharper features, but they otherwise look very similar.

Marumitsu has a wife in each wing of his residence, and each of them is mother to one of the protagonists. In the original story and in Torikae baya, his brother has four daughters: the two eldest are involved with the current Emperor and Crown Prince, and the youngest, called Shi no Hime (四の姫) in the manga, marries Sara.

Another major character is the chunagon’s amorous and troublemaking colleague, whose rank for most of the story is saisho no chujo (宰相中将). As with some of the other major characters, Saito gives him a more memorable name: Tsuwabuki (石蕗).

In both versions, the current Emperor abdicates early on in the story, allowing the Crown Prince (東宮) to take his place. Neither having a male heir, the title of 東宮 shifts to the abdicated Emperor’s daughter, who becomes known as 女東宮 (basically, “girl crown prince” – fascinatingly, the Nihon Kokugo Daijiten lists Torikaebaya monogatari as the earliest known appearance of this term). So far, I’ve been pencilling in both her and the first Crown Prince with the transliteration Togu.

Some characters in Torikae baya do have counterparts in the original story but are otherwise different in significant ways. Umetsubo (梅壺) is a member of the abdicated Emperor’s harem who, in Torikaebaya monogatari, appears just once, and we learn nothing about her, but in Torikae baya, she becomes a major antagonist.

Yoshino no miya (吉野の宮)’s counterpart in the original tale shares a similar backstory, but notably has two half-Chinese daughters; in Torikae baya, he is instead implied to be another character’s father (I won’t say whose just yet!).

One more example is the manga character San no Hime (三の姫), who plays quite a big role in the second half of the series, but is based on a character who is only ever really implied in the original – the udaijin’s unaccounted-for third daughter.

And this is definitely not an exhaustive list! Plenty more characters are identified throughout the manga, but these are at least most of the major ones. As you often see in a multi-volume series, there are handy relationship charts to kick off most volumes. At some point down the line, I might try to throw together an expanded version of those myself!