More thoughts from Episode 13: Yume no Wada

Like I said in the previous post, Episode 13 is one of two chapters that I initially translated a year ago, and that means I’ve had time to think about it a bit more than some of the others. On that note, I’d like to write about it some more, and use an example from Episode 13 to return to a topic from another earlier blog post: poetry!

One of the things that’s so interesting about Torikae baya is that it doesn’t always directly follow the source material, but includes adjustments and additions to the story. Many of the additions serve to give more detail to the world by giving readers a sense of what life in the capital was like in the Heian period, such as by showing various annual ceremonies. There are also references to other works of classical literature, from the Heian period or earlier.

In that earlier post about poetry, I talked about how important writing and sharing poetry was in Heian court culture and how Saito features some of the exact poems that appear in the original Torikaebaya monogatari, but not all of them come from there. And rather than attempt to produce poetry in classical language herself, Saito includes poems from other classical sources.

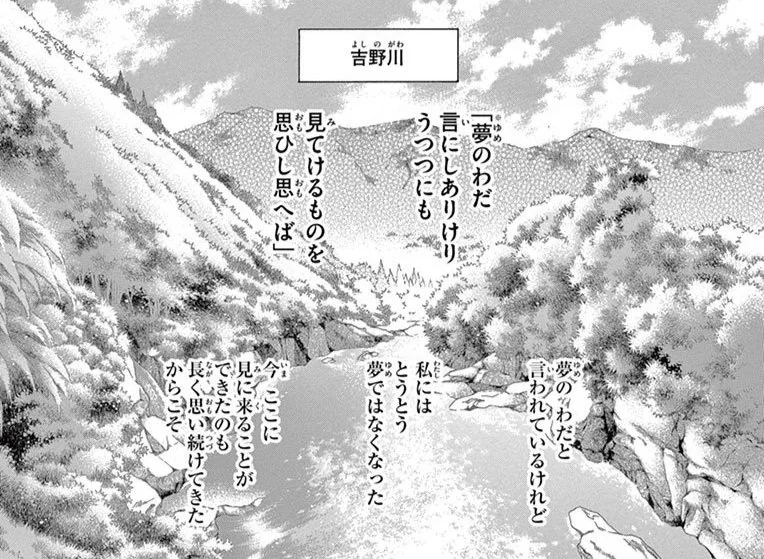

Panel from volume 3, page 79.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

At the beginning of Episode 13, Togu and her entourage reach Yoshino, and the chapter opens with her looking out upon a body of water where two rivers, the Yoshinogawa and Kisadanigawa, meet. She then appears to recite a poem, shown first in classical Japanese, and then followed by an explanatory modern Japanese version:

夢のわだ 言にしありけり うつつにも 見てけるものを 思ひし思へば

(夢のわだと言われているけれど 私にはとうとう夢ではなくなった 今ここに見にくることができたのも長く思い続けてきたからこそ)

This poem comes from the Man’yoshu, one of the most significant poetry anthologies in Japan, which was compiled by some time in the Nara period (710-794 CE). That means that we aren’t expected to imagine that Togu just came up with this by herself, but that she too is referring to well-known existing literature. It’s a very apt poem for her situation, as it is about the place she’s visiting! Yume no Wada (which translates roughly to “pool/ravine of dreams”) is a name for this location, and in the poem, the narrator shares the feeling of finally seeing it for themselves after having wanted to for a long time.

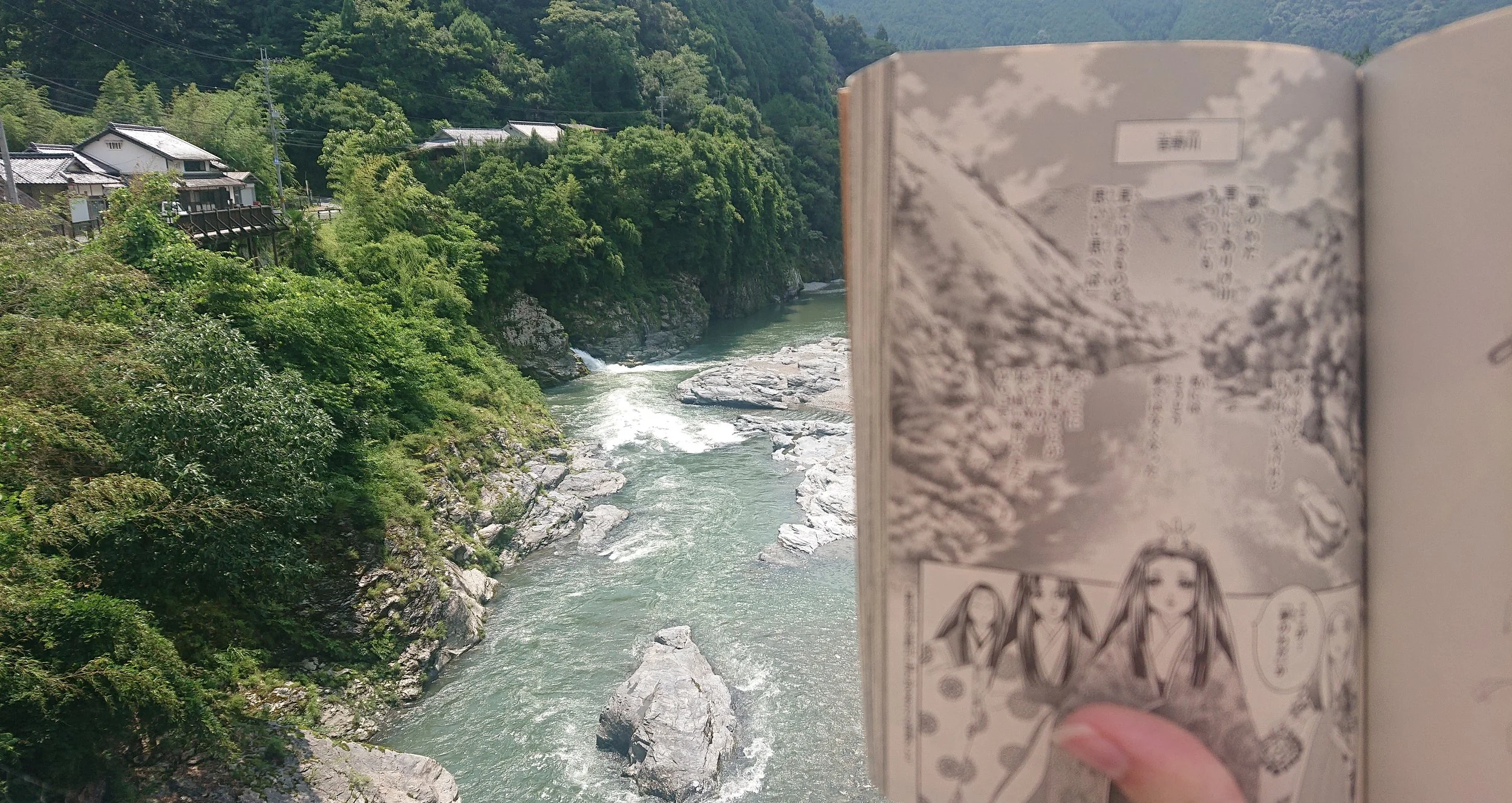

When I first tried translating this, I had to rely heavily on the modern Japanese version provided as well as other modern glosses and explanations available (like this one and this one). But I can now approach it a bit differently, as I’ve recently been in Japan studying classical Japanese (kobun) and visiting locations including Yume no Wada!

Learning how to read classical Japanese obviously helped me to understand poems like this one. I should point out that since “classical Japanese” refers mainly to the language as used in the Heian period, there are aspects of Nara period usage that are different from what I studied – this might be why there are expressions in the poem I can’t just conveniently find in my classical dictionary! Still, being able to analyse a poem like this and at least work out which parts require additional research makes the task much more realistic.

And going there in person was also helpful! At first, I had “wada” down as “cove”, because even with dictionary entries and the detailed image in the manga, it was hard for me to quite understand the nature of this bit of water. From seeing it for myself, I understand that the Kisadanigawa is much narrower than the Yoshinogawa, and that where the narrow part feeds into the wider river, it forms this slower-moving patch of water.

And so, armed with this knowledge, I feel better able to do justice to this interesting use of additional literary references! Here is my current translation:

“Yume no Wada” / is but a name. / Wide awake, / I have now seen it, / just as I long dreamt.

(They call it the Pool of Dreams, but it is not merely a dream to me any longer. I have finally come to see it for myself, all because I desired to for so long.)

I like to think that now that I know more and I’ve given it some deeper thought, I’ve come up with a decent translation. Something that was actually quite handy about rendering this in English is that “dream” can be used to mean “long for [something]”, letting me incorporate the poem’s contrast between dreams and reality in a slightly different way that meant I could keep the order of information the same as in the original poem. Meanwhile, having the lengthier modern version as an opportunity to go into more detail about the meaning allowed me to stick to something brief and abstract for the poem itself.

And of course, it wasn’t lost on me that making a pilgrimage to the spot where Togu cites the poem about finally seeing the “pool of dreams” in real life doubled up on the original reference. So to commemorate the dream-versus-reality within a dream-versus-reality, I also recited the poem and took a picture of the manga page next to its real-world counterpart!