Blogging about my Torikae baya manga translation project.

Thoughts from Episode 33: Life is but a dream

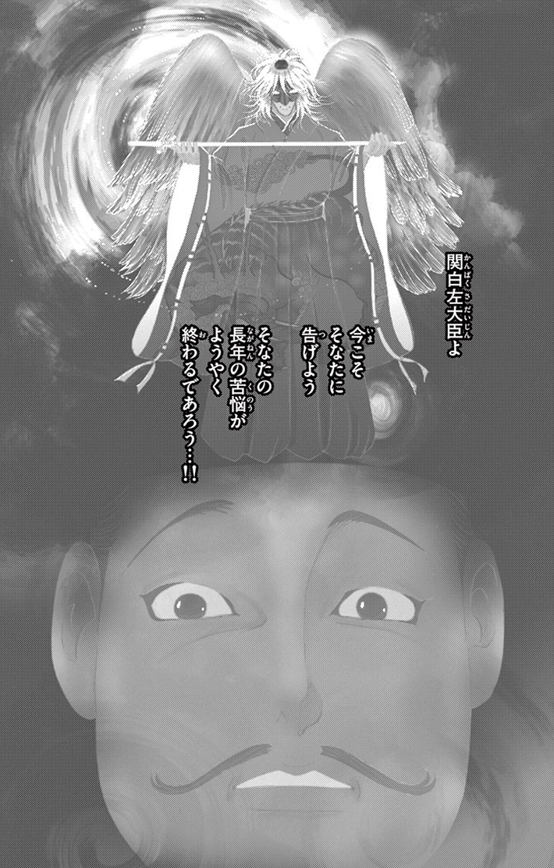

Episode 33 begins with the image of a tengu, appearing in Marumitsu’s dreams as a voice informs him that his children’s karmic debts have been repaid and they will return shortly. He then wakes up to learn that it’s true! Sara and Suiren are back to pick up each other’s lives where they left off, and their parents are overjoyed.

The news of their return soon reaches others: Kakumitsu, who is persuaded to take Shi no Hime and her children back in, and Tsuwabuki, who is too shocked about “Sara” coming back to even think about Shi no Hime. Tsuwabuki makes his way to the palace on the day Suiren arrives to take over Sara’s old job, approaching Suiren with his typical degree of discretion and earning himself a kick in the head. Later, the Emperor receives Suiren and expresses his relief that “Sara” is back at court.

Episode 33 begins with the image of a tengu, appearing in Marumitsu’s dreams as a voice informs him that his children’s karmic debts have been repaid and they will return shortly. He then wakes up to learn that it’s true! Sara and Suiren are back to pick up each other’s lives where they left off, and their parents are overjoyed.

The news of their return soon reaches others: Kakumitsu, who is persuaded to take Shi no Hime and her children back in, and Tsuwabuki, who is too shocked about “Sara” coming back to even think about Shi no Hime. Tsuwabuki makes his way to the palace on the day Suiren arrives to take over Sara’s old job, approaching Suiren with his typical degree of discretion and earning himself a kick in the head. Later, the Emperor receives Suiren and expresses his relief that “Sara” is back at court.

Finally, the real Sara shows up at the Nashitsubo pavilion with Torako and other attendants to begin work as the naishi no kami… only to meet another naishi no kami: Kakumitsu’s daughter San no Hime.

Marumitsu dreams of the tengu.

From volume 7, page 77. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

And so, the big switch that Sara and Suiren prepared for last time is now complete. Marumitsu’s dream at the start of this chapter is, of course, equivalent to a key scene in the Heian period tale – a scene that I never tire of pointing out as the only time a tengu is mentioned in the source material. As such, I devoted quite a bit of time to working out how this scene is adapted and how to put that into English. Broadly speaking, it stays quite close to the original scene, though the visual focus is on the tengu, whereas the original suggests that Marumitsu only sees a priest who tells him about the tengu. Of the different versions, Saito’s wording is probably closest to Kuwabara Hiroshi’s modern Japanese translation, but with the notable distinction of omitting any specific mentions of the man’s children and their genders. Therefore, where other versions clearly state “[the tengu] changed the boy into a girl, the girl into a boy” and “the man will be a man and the woman a woman” (both from Willig’s translation), the manga avoids saying quite what the punishment was and quite what the remedy is. In fact, Marumitsu doesn’t seem certain either – the dream voice tells him “all things should soon settle rightly into their right places” and he then wakes up wondering what “rightly” (しかるべき) was supposed to mean.

Even apart from this big moment, references to dreams loom pretty large in Torikaebaya monogatari. Willig characterises the tale as a giko monogatari, a genre that is openly derivative of existing courtly literature (particularly The Tale of Genji) and notes “dreams” as one of the genre’s typical themes. One of the main ways this comes across in the original text is the many moments where an incident is described as “like a dream” (or some similar variation). The “dreamlike” description is applied frequently but not exclusively to dubiously consensual sex scenes, which I imagine has some connection to the figuratively and literally murky reality of courtship among the Heian nobility. I could swear I’ve read about this phenomenon occurring in other Heian literature too, but I couldn’t come up with a source on it today. Torikae baya, being in a visual medium, doesn’t reflect this tendency so much, but there is a moment early in Tsuwabuki’s affair with Shi no Hime when he wonders sadly if their night together was just a “sweet dream” never to reoccur.

Dreams are also associated with Yoshino no Miya in both the source material and the manga, with dream interpretation being one of his many areas of mystical knowledge. When the chunagon first leaves for Yoshino in the original story, he tells people he needs to take a break on the advice of a dream interpreter. This is apparently meant to put them off his scent, which I must say seems a bit counterintuitive, but at least it shows that people were taking dream interpretation very seriously! Anyway, it makes sense that Yoshino is an expert on these matters, as he serves an important role in the story as somebody with knowledge of the past and future and of the siblings’ secret. This is especially important in the manga, where he’s also closely associated with the tengu. Incidentally, Willig suggests in passing that he is connected to Marumitsu’s dream in the original story too, but so far I’ve found nothing to back this up.

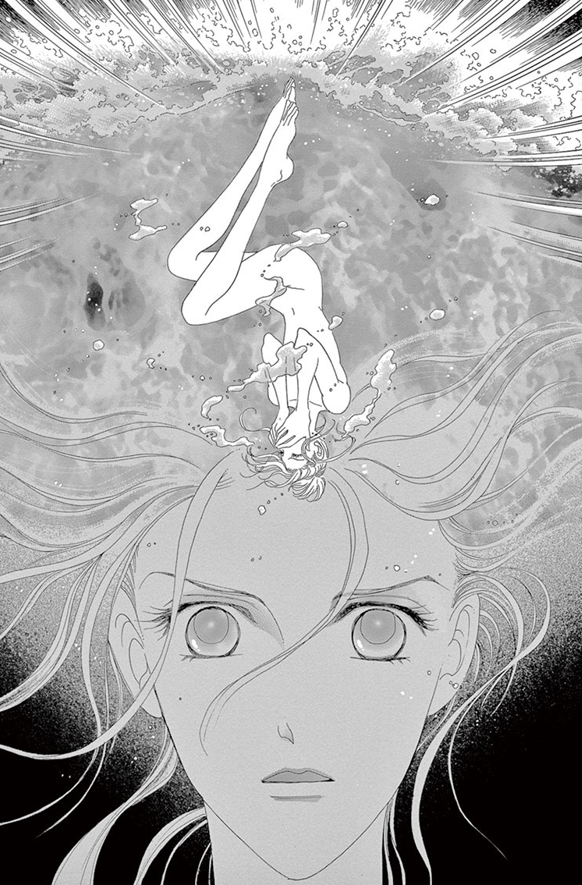

Sara dreams of drowning.

From volume 4, page 57. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

Anyway, in the Torikae baya manga, the most common references to dreams are just dreams themselves! In Episode 3, Sara dreams about the “tengu” that kidnapped him and Suiren as children, and indicates that isn’t the first time. This dream shakes up the narrative of the story by revealing the idea of the tengu’s curse much earlier and treating it as something that weighs on the siblings’ minds, and because it is also a premonition of the eclipse incident, it gives Sara an early emotional connection to the future Emperor. And when things go wrong later, he and Suiren both suffer from nightmares: after his night with Tsuwabuki, Sara dreams that he is drowning (foreshadowing his suicide attempt in Uji), and following Sara’s disappearance, Suiren is plagued with confused thoughts about where he has gone and why. Similar moments occur later in the series too, including ones that call back to earlier dreams.

Altogether, I find that all these dreams – the ones experienced by the characters and the passing allusions to dreaming – serve two main purposes. In the overall narrative, they help to tie things together, giving the reader hints of what is to come and providing some explanation for events. But maybe more importantly, they contribute to a sense of ambiguity. The characters and the reader can’t always tell what is real, and distinctions aren’t always clear-cut. And as Togu suggests when she gazes out on the aptly named Yume no Wada and can’t help but quote the Man’yoshu, dreams and reality may not be so far apart.

Thoughts from Episode 31: Return to Yoshino

After spending quite a bit of time on the previous chapter (two posts over three weeks), let’s finally move on to Episode 31, the beginning of volume 7! Sara and Suiren have been reunited, Sara instructs Aguri – who imagines she’s seeing two of the same person – to let Tsuwabuki think Sara has vanished into thin air while the siblings head for Yoshino. There, they tell Yoshino no Miya of their intention to take up religious vows, and lament together about how they have ended up in this situation.

After spending quite a bit of time on the previous chapter (two posts over three weeks), let’s finally move on to Episode 31, the beginning of volume 7! Sara and Suiren have been reunited, Sara instructs Aguri – who imagines she’s seeing two of the same person – to let Tsuwabuki think Sara has vanished into thin air while the siblings head for Yoshino. There, they tell Yoshino no Miya of their intention to take up religious vows, and lament together about how they have ended up in this situation.

One day, the Emperor appears. Sara and Suiren eavesdrop as he seeks Yoshino’s advice regarding troubles at court and asks him to return to political life in Heian-kyo. Yoshino turns down the request and informs the Emperor that the real reason he was previously banished from the capital was because he coveted the former Emperor’s consort. Eventually, the current Emperor reluctantly accepts Yoshino’s refusal and goes on his way.

Sara and Suiren, having heard about the difficulties in the capital – including their father being literally worried sick about them and Togu being left without supporters – question whether they are doing the right thing in abandoning the secular world. At last, they decide to switch places (立場をとりかえ) and return to Heian-kyo.

This chapter is titled “The Secret of Yoshino” (吉野の秘め事), and as such, I’d like to get a bit more into Yoshino no Miya and his backstory. I did give him a little introduction earlier, but Episode 31 reveals details that were previously murky.

Page from volume 7, page 31.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

So who is he? He refers to Suzakuin (the former Emperor) as his cousin, and therefore he is also a cousin to the current Emperor, who is Suzakuin’s younger brother. At some point in the past, he travelled to China and gained knowledge in esoteric fields such as physiognomy. That presumably occurred before a period ten-plus years prior to the current events, when he was involved in a scandal which resulted in his expulsion from the world of politics. He then secluded himself on the remote Yoshinoyama, where he prays for the safety and prosperity of the people in the capital, especially the imperial family, and especially especially Togu.

In this chapter, we learn the nature of that earlier scandal. Not only was he involved in a succession dispute with Suzakuin, but he lost that dispute – and we can deduce that that probably resulted in Suzakuin ascending the throne soon afterwards. Even worse, he desired Suzakuin’s late wife, and may well be the illegitimate father of the current Togu. When the current Emperor directly questions him about this in Episode 31, he denies that his relationship with Suzakuin’s wife reached that point, but the implication is that the stories are true. Of course, this would make his particular attachment to Togu make a lot of sense!

It’s also interesting when we compare his character to his counterpart in the original Torikaebaya monogatari. There, Yoshino no Miya has two beautiful daughters, whose mother was Yoshino’s Chinese wife who tragically died, leading him to take them back to Japan with him. He feels a responsibility to remain hidden away on Yoshinoyama, but wishes that his daughters could leave and live a more normal life; he gets his wish when Sara’s counterpart takes an interest in the elder daughter and Suiren’s counterpart later marries her in his stead. In the manga, Suzakuin’s late wife is the equivalent of Yoshino’s late wife, and Togu – as Suiren’s only love interest and Yoshino’s implied illegitimate daughter – turns out to be a composite character of the original Togu and Yoshino’s daughters.

And while revealing these dramatic details in Episode 31, Yoshino says one other interesting thing. As he insists that it was only right for him to driven away from the capital, he refers to himself as “the great tengu that sows chaos across the land” (天下を乱す大天狗). Now, a “tengu” can also figuratively mean an arrogant person, which would be a plausible interpretation in this context, but it isn’t the first time he’s been associated with tengu. On his very first appearance, his skills, his knowledge and his clothing led Sara and Suiren to mistake him for a tengu, and since then, he has made remarks about turning his back on a dark past. For him to call himself a “tengu” now – just before the only part of the original story where the tengu is mentioned – comes across as more than just a figure of speech. It suggests that while Togu takes on aspects of Yoshino’s daughters from Torikaebaya monogatari, the tengu’s story also becomes part of Yoshino’s story in this version of the tale.

Thoughts from Episode 21: You only live twice

At the end of the previous chapter – and volume – Sara had what seemed horribly like morning sickness. This time, he goes to see his former wetnurse Aguri, whom he used to visit for a few days every month until very recently, to subtly ask about the typical symptoms of pregnancy. He soon concludes that it is just as he feared, then takes a week off from work to go and see Yoshino no Miya, the only person he can think to confide in.

At the end of the previous chapter – and volume – Sara had what seemed horribly like morning sickness. This time, he goes to see his former wetnurse Aguri, whom he used to visit for a few days every month until very recently, to subtly ask about the typical symptoms of pregnancy. He soon concludes that it is just as he feared, then takes a week off from work to go and see Yoshino no Miya, the only person he can think to confide in.

Sara tells Yoshino he wants to die, but Yoshino tries to change his mind. He suggests that Sara has the ability to “die” once and then live a second life, implying that he has done something similar himself. In the end, Sara is inspired to persevere, but remains unsure of what to do.

Meanwhile, Tsuwabuki is indiscreetly snooping, and in his attempts to find out where Sara is, he ends up speaking to Shikibu-kyo no Miya, who reveals that Sara had just returned to speak to him. In fact, Sara is listening right at that moment, and isn’t too pleased about Tsuwabuki’s loud mouth. Afterwards, they have an argument, Sara collapses, and when Tsuwabuki insists on fetching a doctor, Sara blurts out the truth about his pregnancy.

Since early in the story, fate has been an important recurring theme in Torikae baya. Sara and Suiren’s peculiarities and their troubles are attributed to karma from their past lives, and when things go wrong, it can feel a lot like they’re helpless to make it better. But at the same time, the issue of fate is an area where the manga actually challenges the source material a bit: a topic that came up when I spoke to Saito was that the original story has quite a stern Buddhist outlook and that she wanted to make her version more “positive”.

That’s something that comes across strongly in this chapter. When Sara realises what has happened and questions what to do, he believes there’s no way he can go on living. He thinks of the tengu that supposedly cursed him and Suiren – the most prominent representative of fate in the manga – and asks if it is a shinigami, coming to take him away.

Panel from volume 5, page 24.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

Immediately afterwards, he visits Yoshino no Miya, whose mysterious power to predict the future also reflects the significance of fate. Indeed, Yoshino is associated with the tengu, but an important difference is that he emphasises Sara’s power to make his own decisions. Sara, despairing, wants to be told what to do, and he responds:

I will not tell you whether to have the baby,

or whether to join the priesthood!

What you do with the rest of your life

is something you must decide for yourself!

As much as Yoshino uses divination to claim that Sara is destined for a bright future, he also suggests that it’s up to Sara to shape that destiny. He tells Sara he’s reached a fork in the road (分かれ道 – this is also the title of the chapter!) where he needs to decide on a new course of action. And in Yoshino’s idea about living one life and then another, there is the suggestion that even one’s ultimate fate needn’t be truly final.

And so, even though the siblings still go through plenty of hardship in Saito’s version of the story, they’re portrayed as having the agency to control how their lives pan out. They ultimately make their own decisions, for better or for worse.

Thoughts from Episode 13: An encounter with a tengu (?)

It’s been a while again! I’ve been on a trip, which is still ongoing, and it’s kept me a bit too busy to cope with weekly posts (especially yesterday, which was a VERY big day!). On the bright side, as I indicated last time, it is at least a trip that will give me plenty more to say at a later date. Look out for that in a few weeks’ time!

Anyway, we left Sara, Suiren and Nanten no Togu last time as they were approaching Yoshino. Yoshino was known even back then for cherry blossoms, but as our friends are going there in summer, Sara suggests the more seasonal activity of firefly catching. He brings Suiren and some attendants, but Sara and Suiren soon become separated from the group and encounter what appears to be a tengu.

It’s been a while again! I’ve been on a trip, which is still ongoing, and it’s kept me a bit too busy to cope with weekly posts (especially yesterday, which was a VERY big day!). On the bright side, as I indicated last time, it is at least a trip that will give me plenty more to say at a later date. Look out for that in a few weeks’ time!

Anyway, we left Sara, Suiren and Nanten no Togu last time as they were approaching Yoshino. Yoshino was known even back then for cherry blossoms, but as our friends are going there in summer, Sara suggests the more seasonal activity of firefly catching. He brings Suiren and some attendants, but Sara and Suiren soon become separated from the group and encounter what appears to be a tengu. Sara boldly tries to attack the “tengu” only to get knocked out and taken away, followed by Suiren. The “tengu” speaks to them in his villa when Sara wakes up, and immediately works out the siblings’ big secret.

The next day, Sara and Suiren are back with Togu, who has heard they had an adventure – when suddenly, the “tengu” appears! It turns out that he is none other than Yoshino no Miya, a reclusive member of the imperial family. He and Togu discuss the difficulties going on back in the capital, which she worries is the result of having a girl as the heir to the throne. Yoshino tries to console her and talks about destiny. He later sends Sara and Suiren on their way, makes some more mysterious comments and says he is sure they will be back.

Finally, Sara returns to Kakumitsu’s residence just as Tsuwabuki is leaving. Tsuwabuki makes an awkward excuse for being in the area and goes on his way, but Sara then goes to see Shi no Hime and smells something that reminds him of a certain work colleague…

Episode 13 is actually the first chapter that I translated! About this time last year, I did a translation pilot to test out my approach and the format of the translation, so I decided to select two consecutive chapters that were fairly representative, had plenty of variety and exhibited a lot of what makes Torikae baya interesting. That means I actually dealt with Episodes 13 and 14 quite a long time ago – but of course they could do with some updates considering everything I’ve been doing since.

Panel from volume 3, page 87.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

One of the great things about this chapter is that it introduces Yoshino no Miya! He has an equivalent in the original Torikaebaya monogatari, but like many of the characters in the manga, his role and characterisation are expanded here. He is a learned man who has studied various esoteric subjects in China, and was once an important figure at court until he left amid controversy and became an ascetic.

When Sara and Suiren first encounter him, both are immediately reminded of the tengu that is supposed to have cursed them – something I talked about in a much earlier blog post. They have this impression because, like the tengu gang from Episode 1, Yoshino is dressed in the clothes of a yamabushi. His divination skills – predicting years earlier that the Togu we know would become Togu, determining Sara and Suiren’s secret just by looking at their faces – also contribute to the sense that he is supernatural in some way.

I’ve mentioned previously that the idea of the tengu’s curse is greatly expanded in the manga from what was, in the original text, a brief explanation of what the siblings’ deal was and why it had been resolved. Basically, in Torikaebaya monogatari, it is revealed in a dream far into the story that a tengu cursed the father due to bad karma, causing the siblings’ situation, but the curse has now been alleviated.* But in the manga, the siblings believe they themselves are cursed and don’t know what to do about it.

*In the published version of Willig’s translation, this is attributed to the father becoming a devout Buddhist – maybe due to editing an ambiguous line in the first version – but a reviewer said it was actually the tengu that found religion. Incidentally, the original original wording genuinely does seem quite ambiguous.

Combined with associations between tengu, yamabushi and other monks, this could be a reason for Torikae baya’s Yoshino to be repeatedly identified with the tengu. Apart from this first appearance, he also later compares himself with a tengu, he is very knowledgeable about fate/destiny, and he treats his old difficulties at court as a dark past he has struggled to turn his back on.

Altogether, we end up with a fascinating character and an important layer of the tengu/curse motif in Torikae baya, which is, for me, one of the most interesting examples of the manga expanding on aspects of the original story.

Thoughts from Episode 3: The Eclipse

After Episode 2 showed Sara starting his exciting new job working for the Emperor and meeting his new best friend (whether he likes it or not) Tsuwabuki, this chapter gets a bit more dramatic. Tsuwabuki shows up uninvited at Sara’s home with two of his friends, and gets terribly upset that Sara won’t introduce him to Suiren. As it turns out, everybody has heard about Suiren, even the Emperor! This causes Sara to have (apparently for the first time in a while) a nightmare about the tengu from Episode 1. The tengu tells Sara that he and Suiren are cursed, and that the curse will be lifted when the tengu devours the Emperor.

After Episode 2 showed Sara starting his exciting new job working for the Emperor and meeting his new best friend (whether he likes it or not) Tsuwabuki, this chapter gets a bit more dramatic. Tsuwabuki shows up uninvited at Sara’s home with two of his friends, and gets terribly upset that Sara won’t introduce him to Suiren. As it turns out, everybody has heard about Suiren, even the Emperor! This causes Sara to have (apparently for the first time in a while) a nightmare about the tengu from Episode 1. The tengu tells Sara that he and Suiren are cursed, and that the curse will be lifted when the tengu devours the Emperor.

Three important men then show up from the on’yoryo (for now at least, I have this as the Bureau of Yin and Yang – this is where they practised divination, astrology, etc) to reveal that an annular eclipse is coming, and the Emperor immediately falls ill. While everyone in the palace prepares to hide him away from the ominous effects of the eclipse, the Emperor gives his younger brother (Togu, the crown prince) a crystal ball containing an image of Kundali, one of the Five Wisdom Kings. Sara, inspired by another vision of the tengu, decides to risk being cursed by the eclipse in order to break his own curse, and is soon joined by Tsuwabuki and Togu. They go to the roof of a high building, where Togu holds out the crystal ball and prays for rain. Clouds come and obscure the eclipse, and the Emperor recovers.

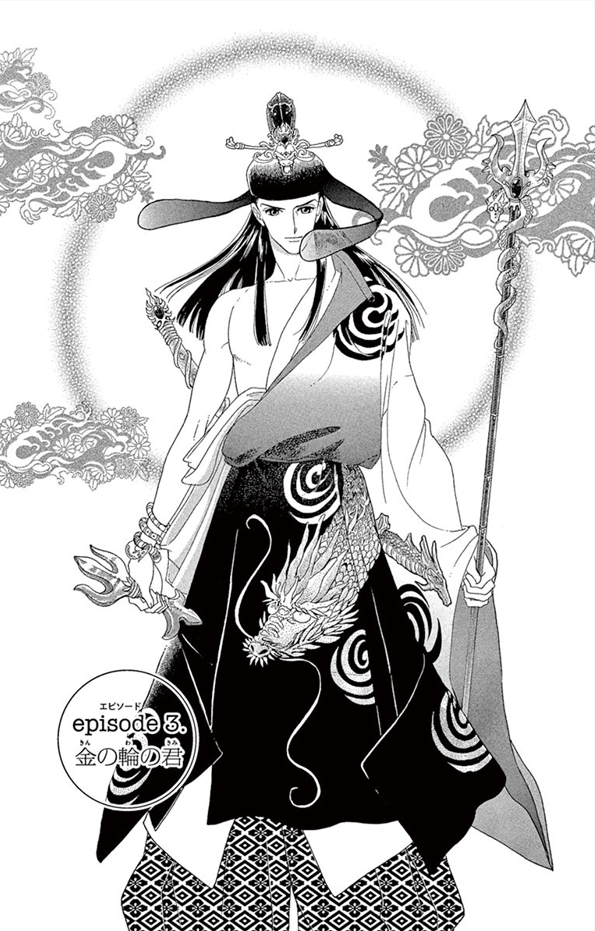

Title page of Episode 3 from volume 1, page 83. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

There are plenty of things to think about in this chapter! There’s new information about the tengu’s curse and how that ties into other aspects of the story, as well as plenty of details about the belief system at the court. Today, though, I’ll just take a look at the chapter’s title – which is quite enough to handle!

Episode 3 is titled 「金の輪の君」 (kin no wa no kimi). This is quite a bit more abstract than previous titles, which were just characters’ names. The meaning of “kin no wa” becomes clear when characters begin talking about the eclipse. The astrologers talk about a 金の環の日食 (kin no wa no nisshoku), referring to the annular eclipse. Usually this is written without the のs, as 金環日食 (kinkan nisshoku), but it’s same in practice, qualifying the eclipse (nisshoku) as one where a golden ring (kin no wa) is visible.

You might notice – not that I did at first! – that the spelling in the dialogue uses the kanji 環 where the title uses 輪. I was trying to figure out what difference this would make and why it would be worth writing it two ways, but I think it’s most likely for practical reasons. In the title, it’s standing alone, and as 輪 is more commonly used for “ring” as a noun, it makes a bit more sense in that context. On the other hand, when it appears again later, it’s in the full “annular eclipse” phrase. It uses the same words, and with the same meaning, but “kinkan nisshoku”, the usual term for an annular eclipse, uses the more abstract 環 and can’t be written with a 輪. Perhaps there is more to it, but that’s the only reason I can see for writing it two different ways.

Another side point here is about the word for eclipse itself: 日食, meaning that the sun is eaten. There are old Chinese myths about monsters eating the sun during an eclipse, including a black dog called the tiangou. This is written as 天狗, the same spelling as “tengu”, which in Japan came to be seen as birdlike monsters such as the ones we see pretty regularly in Torikae baya. So when the dream-tengu tells Sara it’s going to devour the Emperor – whom the people at the court handily point out is symbolised by the sun – it connects closely with old myths about eclipses.

Anyway, what about that title? How should it be translated? As we have the “kin no wa” but not the “nisshoku”, it doesn’t really seem right to translate this as “eclipse”. That would be providing information that the Japanese readers aren’t getting at this point. “Annulus” could make sense as that’s the part that is mentioned, but the fact it’s written as 金の輪 and not 金環 puts me off that too. And there’s a later line that makes me feel that it could be intended to evoke the idea of a halo as well, which then gels with the imagery of the title page. This all makes me lean towards a fairly literal answer, so that I’m not saying more than I should, and so that it remains mysterious. In the end, I came up with “He of the Golden Ring” – interpreting the “kimi” in the same way as it gets used as a term of respect in people’s (usually men’s) names.

I’m just glad not every translation choice is as complicated as this!

More thoughts from Episode 1: The Tengu of Kurama

It took a bit of time to get writing a follow-up to the previous post, because this time last week I was at the JF/BAJS PhD workshop! I talked about my project and heard some great presentations from other postgraduate students working on all kinds of different topics. One thing I prepared for my presentation but didn’t quite have time to elaborate on was Saito’s use of tengu as a recurring motif in Torikae baya. The first appearance of a tengu is in Episode 1, so I’ll say a bit about that today!

It took a bit of time to get writing a follow-up to the previous post, because this time last week I was at the JF/BAJS PhD workshop! I talked about my project and heard some great presentations from other postgraduate students working on all kinds of different topics. One thing I prepared for my presentation but didn’t quite have time to elaborate on was Saito’s use of tengu as a recurring motif in Torikae baya. The first appearance of a tengu is in Episode 1, so I’ll say a bit about that today!

In Torikaebaya monogatari, there is a section in the middle of the story where the chunagon (Sarasoju’s counterpart) leaves Heian-kyo and the naishi no kami (Suiren’s counterpart) goes in search of him. During this time, their father is worried sick – mainly about the chunagon, because the naishi no kami’s role is so behind-closed-doors that nobody even notices she’s gone. The naishi no kami goes to Yoshino, learns that the chunagon is in Uji, and has the bright idea for them to switch roles and return to ease their father’s worries. Just as the naishi no kami is coming back to tell him the good news, the father has a dream. In the dream, he is told that his children were the way they were because of a tengu’s curse (“goblin” in Willig’s translation), but now the curse has been lifted and they will take on their “proper” roles.

This is the first and last mention of a tengu in the original story, but Saito takes it much further, presenting the tengu’s curse as something that Sara and Suiren themselves are worried about throughout the series. In Episode 1, we first encounter tengu when a young Sara and Suiren are on their way to the temple in Kurama, north of Heian-kyo, where their father Marumitsu hopes their odd behaviour can be set right. Kurama has a long association with tengu, and though that isn’t specified in the manga, Sara does remark on having heard tales of tengu descending from the mountains to snatch up children. Mountain locations, and especially the yamabushi (mountain ascetics) found there, are another link to tengu that will be important later in the manga.

Panel from volume 1, page 27. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

During the journey to Kurama, a gang of apparent tengu show up to ransack the palanquins, unceremoniously killing the servants in the process. They’re disappointed not to find much of value, with the exception of two pretty kids they can sell to some unnamed lecherous priest. Sara comes up with a risky escape plan: if the two switch clothes, Sara can attack/distract the tengu, allowing them both to run away. And it works! Sara discovers that the bandits can’t fly and aren’t real tengu, and he manages to lead Suiren to safety. This is a crucial moment, showing us that Sara and Suiren are better for not fitting their expected gender roles. It also sets up tengu as a source of fear, and as something that maybe is and maybe isn’t real.

Nowadays, tengu are often portrayed as generally humanoid but red and with an extremely long nose – and something like this does appear once later in Torikae baya – but this image is a comparatively recent development. In contrast, the gang of bandits that appear in this chapter wear beaklike masks and yamabushi-esque garments, and have unkempt hair. I’m not totally sure if all of these aspects are accurate to the time period, but the idea of tengu as sneaky bird-men who kidnap people existed by the time of Konjaku monogatarishu, which is from roughly the same time as Torikaebaya monogatari (late Heian).

Anyway, that’s as much as I’ll get into about tengu today, but you can expect to hear more about them soon!