Blogging about my Torikae baya manga translation project.

More thoughts from Episode 13: Yume no Wada

Like I said in the previous post, Episode 13 is one of two chapters that I initially translated a year ago, and that means I’ve had time to think about it a bit more than some of the others. On that note, I’d like to write about it some more, and use an example from Episode 13 to return to a topic from another earlier blog post: poetry!

Like I said in the previous post, Episode 13 is one of two chapters that I initially translated a year ago, and that means I’ve had time to think about it a bit more than some of the others. On that note, I’d like to write about it some more, and use an example from Episode 13 to return to a topic from another earlier blog post: poetry!

One of the things that’s so interesting about Torikae baya is that it doesn’t always directly follow the source material, but includes adjustments and additions to the story. Many of the additions serve to give more detail to the world by giving readers a sense of what life in the capital was like in the Heian period, such as by showing various annual ceremonies. There are also references to other works of classical literature, from the Heian period or earlier.

In that earlier post about poetry, I talked about how important writing and sharing poetry was in Heian court culture and how Saito features some of the exact poems that appear in the original Torikaebaya monogatari, but not all of them come from there. And rather than attempt to produce poetry in classical language herself, Saito includes poems from other classical sources.

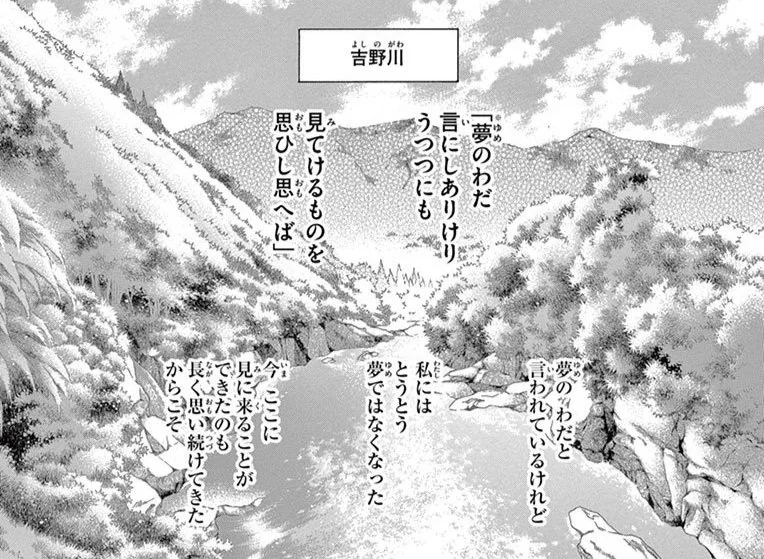

Panel from volume 3, page 79.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

At the beginning of Episode 13, Togu and her entourage reach Yoshino, and the chapter opens with her looking out upon a body of water where two rivers, the Yoshinogawa and Kisadanigawa, meet. She then appears to recite a poem, shown first in classical Japanese, and then followed by an explanatory modern Japanese version:

夢のわだ 言にしありけり うつつにも 見てけるものを 思ひし思へば

(夢のわだと言われているけれど 私にはとうとう夢ではなくなった 今ここに見にくることができたのも長く思い続けてきたからこそ)

This poem comes from the Man’yoshu, one of the most significant poetry anthologies in Japan, which was compiled by some time in the Nara period (710-794 CE). That means that we aren’t expected to imagine that Togu just came up with this by herself, but that she too is referring to well-known existing literature. It’s a very apt poem for her situation, as it is about the place she’s visiting! Yume no Wada (which translates roughly to “pool/ravine of dreams”) is a name for this location, and in the poem, the narrator shares the feeling of finally seeing it for themselves after having wanted to for a long time.

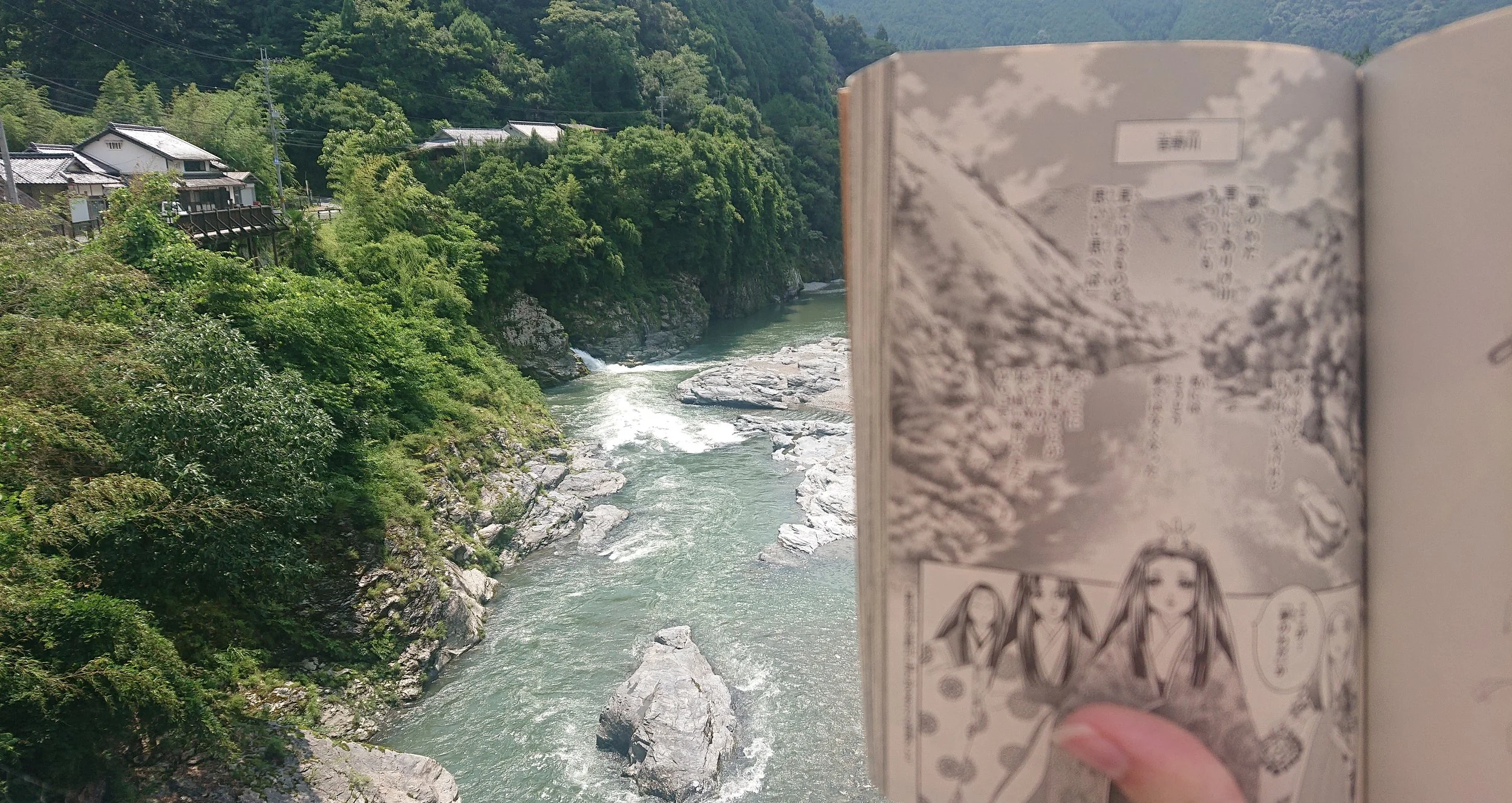

When I first tried translating this, I had to rely heavily on the modern Japanese version provided as well as other modern glosses and explanations available (like this one and this one). But I can now approach it a bit differently, as I’ve recently been in Japan studying classical Japanese (kobun) and visiting locations including Yume no Wada!

Learning how to read classical Japanese obviously helped me to understand poems like this one. I should point out that since “classical Japanese” refers mainly to the language as used in the Heian period, there are aspects of Nara period usage that are different from what I studied – this might be why there are expressions in the poem I can’t just conveniently find in my classical dictionary! Still, being able to analyse a poem like this and at least work out which parts require additional research makes the task much more realistic.

And going there in person was also helpful! At first, I had “wada” down as “cove”, because even with dictionary entries and the detailed image in the manga, it was hard for me to quite understand the nature of this bit of water. From seeing it for myself, I understand that the Kisadanigawa is much narrower than the Yoshinogawa, and that where the narrow part feeds into the wider river, it forms this slower-moving patch of water.

And so, armed with this knowledge, I feel better able to do justice to this interesting use of additional literary references! Here is my current translation:

“Yume no Wada” / is but a name. / Wide awake, / I have now seen it, / just as I long dreamt.

(They call it the Pool of Dreams, but it is not merely a dream to me any longer. I have finally come to see it for myself, all because I desired to for so long.)

I like to think that now that I know more and I’ve given it some deeper thought, I’ve come up with a decent translation. Something that was actually quite handy about rendering this in English is that “dream” can be used to mean “long for [something]”, letting me incorporate the poem’s contrast between dreams and reality in a slightly different way that meant I could keep the order of information the same as in the original poem. Meanwhile, having the lengthier modern version as an opportunity to go into more detail about the meaning allowed me to stick to something brief and abstract for the poem itself.

And of course, it wasn’t lost on me that making a pilgrimage to the spot where Togu cites the poem about finally seeing the “pool of dreams” in real life doubled up on the original reference. So to commemorate the dream-versus-reality within a dream-versus-reality, I also recited the poem and took a picture of the manga page next to its real-world counterpart!

Thoughts from Episode 13: An encounter with a tengu (?)

It’s been a while again! I’ve been on a trip, which is still ongoing, and it’s kept me a bit too busy to cope with weekly posts (especially yesterday, which was a VERY big day!). On the bright side, as I indicated last time, it is at least a trip that will give me plenty more to say at a later date. Look out for that in a few weeks’ time!

Anyway, we left Sara, Suiren and Nanten no Togu last time as they were approaching Yoshino. Yoshino was known even back then for cherry blossoms, but as our friends are going there in summer, Sara suggests the more seasonal activity of firefly catching. He brings Suiren and some attendants, but Sara and Suiren soon become separated from the group and encounter what appears to be a tengu.

It’s been a while again! I’ve been on a trip, which is still ongoing, and it’s kept me a bit too busy to cope with weekly posts (especially yesterday, which was a VERY big day!). On the bright side, as I indicated last time, it is at least a trip that will give me plenty more to say at a later date. Look out for that in a few weeks’ time!

Anyway, we left Sara, Suiren and Nanten no Togu last time as they were approaching Yoshino. Yoshino was known even back then for cherry blossoms, but as our friends are going there in summer, Sara suggests the more seasonal activity of firefly catching. He brings Suiren and some attendants, but Sara and Suiren soon become separated from the group and encounter what appears to be a tengu. Sara boldly tries to attack the “tengu” only to get knocked out and taken away, followed by Suiren. The “tengu” speaks to them in his villa when Sara wakes up, and immediately works out the siblings’ big secret.

The next day, Sara and Suiren are back with Togu, who has heard they had an adventure – when suddenly, the “tengu” appears! It turns out that he is none other than Yoshino no Miya, a reclusive member of the imperial family. He and Togu discuss the difficulties going on back in the capital, which she worries is the result of having a girl as the heir to the throne. Yoshino tries to console her and talks about destiny. He later sends Sara and Suiren on their way, makes some more mysterious comments and says he is sure they will be back.

Finally, Sara returns to Kakumitsu’s residence just as Tsuwabuki is leaving. Tsuwabuki makes an awkward excuse for being in the area and goes on his way, but Sara then goes to see Shi no Hime and smells something that reminds him of a certain work colleague…

Episode 13 is actually the first chapter that I translated! About this time last year, I did a translation pilot to test out my approach and the format of the translation, so I decided to select two consecutive chapters that were fairly representative, had plenty of variety and exhibited a lot of what makes Torikae baya interesting. That means I actually dealt with Episodes 13 and 14 quite a long time ago – but of course they could do with some updates considering everything I’ve been doing since.

Panel from volume 3, page 87.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

One of the great things about this chapter is that it introduces Yoshino no Miya! He has an equivalent in the original Torikaebaya monogatari, but like many of the characters in the manga, his role and characterisation are expanded here. He is a learned man who has studied various esoteric subjects in China, and was once an important figure at court until he left amid controversy and became an ascetic.

When Sara and Suiren first encounter him, both are immediately reminded of the tengu that is supposed to have cursed them – something I talked about in a much earlier blog post. They have this impression because, like the tengu gang from Episode 1, Yoshino is dressed in the clothes of a yamabushi. His divination skills – predicting years earlier that the Togu we know would become Togu, determining Sara and Suiren’s secret just by looking at their faces – also contribute to the sense that he is supernatural in some way.

I’ve mentioned previously that the idea of the tengu’s curse is greatly expanded in the manga from what was, in the original text, a brief explanation of what the siblings’ deal was and why it had been resolved. Basically, in Torikaebaya monogatari, it is revealed in a dream far into the story that a tengu cursed the father due to bad karma, causing the siblings’ situation, but the curse has now been alleviated.* But in the manga, the siblings believe they themselves are cursed and don’t know what to do about it.

*In the published version of Willig’s translation, this is attributed to the father becoming a devout Buddhist – maybe due to editing an ambiguous line in the first version – but a reviewer said it was actually the tengu that found religion. Incidentally, the original original wording genuinely does seem quite ambiguous.

Combined with associations between tengu, yamabushi and other monks, this could be a reason for Torikae baya’s Yoshino to be repeatedly identified with the tengu. Apart from this first appearance, he also later compares himself with a tengu, he is very knowledgeable about fate/destiny, and he treats his old difficulties at court as a dark past he has struggled to turn his back on.

Altogether, we end up with a fascinating character and an important layer of the tengu/curse motif in Torikae baya, which is, for me, one of the most interesting examples of the manga expanding on aspects of the original story.