Blogging about my Torikae baya manga translation project.

Thoughts from Episode 23: The Flower Festival

The cherry trees are in full bloom on Sara’s last day of work at the imperial court, and he is making a point of going around talking to everybody. By now, he’s clearly getting tired quite quickly, so he has help from Aguri’s daughter Torako and son Toramitsu, whom he’s known since childhood. The palace is in party mood, with Togu asking to see Sara and Suiren together – prompting tears of joy from their father – and court officials reciting Chinese poetry (唐歌, karauta as they call it in the manga). Sara’s recitation is so moving that the Emperor sends him a robe as a gift and later requests a musical performance from him and Suiren as the day comes to an end. Sara instead plays the flute alone and thinks back on his time as a court gentleman.

The cherry trees are in full bloom on Sara’s last day of work at the imperial court, and he is making a point of going around talking to everybody. By now, he’s clearly getting tired quite quickly, so he has help from Aguri’s daughter Torako and son Toramitsu, whom he’s known since childhood. The palace is in party mood, with Togu asking to see Sara and Suiren together – prompting tears of joy from their father – and court officials reciting Chinese poetry (唐歌, karauta as they call it in the manga). Sara’s recitation is so moving that the Emperor sends him a robe as a gift and later requests a musical performance from him and Suiren as the day comes to an end. Sara instead plays the flute alone and thinks back on his time as a court gentleman.

Soon, the Emperor decides Sara deserves a promotion to General (右大将) of the Imperial Guards, but Sara is nowhere to be seen. Unbeknownst to everyone present, he’s already leaving under cover of darkness, with Torako and Toramitsu leading him to an ox-drawn carriage. There, much to his displeasure, he finds Tsuwabuki – as it turns out, Aguri revealed the plans to him and he insisted on helping. In the end, Sara is too exhausted to keep fighting, and the group heads off for Tsuwabuki’s villa in Uji.

I don’t normally do this, but the title of today’s blog post, The Flower Festival, is the same as the chapter title for Episode 23. In Japanese, it’s hana no utage (花の宴), which, like several other chapter titles, is also the title of a chapter in The Tale of Genji. I made an exception this time because it’s particularly apt: not only does the chapter revolve around a flower viewing party in the palace, but it’s also full of meaningful references to flowers.

Title page of Episode 23 from volume 5, page 79.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

In Episode 12, Sara’s personality was compared to spring. Fittingly, on the day he bows out from court service, he’s given the theme of “spring” in the poetry recital. He tastefully recites two consecutive poems by Heian blorbo Bai Juyi from the “last day of the third month” (that is, the end of spring) section of the Wakan roeishu, a famous anthology of Japanese and Chinese poetry. The way this is presented in the manga is as he recites it, not in Chinese but using kanbun kundoku, a traditional of not exactly translating the original poem but converting it to (classical) Japanese grammar. And that’s how we get this:

春 留むるに 春 住まらず

春 帰って 人 寂漠たり

風を厭うに 風 定まらず

風 起って 花 蕭索たり

And this:

竹院に 君 静かにして 永日をけすならん

花亭に 我 酔うて 残んの春を 送る

Now, I can’t just read Chinese as-is, but it does have something distinctive about it, so in my translation, I wanted it to sound a bit different from how I’ve translated the Japanese poems so far. With that in mind, I again took advantage of the fact that we’re shown a classical Japanese and a modern Japanese version. While my translation of the modern Japanese gave me a chance to flesh it out and explain it more, in the first versions I tried to stick quite closely to order of the characters in the original Chinese poems and avoid too many extraneous words in an effort to express their structure. So the first poem ended up like this:

Hold back spring, but it will not stay.

Spring leaves; we are all alone.

Despise the wind, but it will not abate.

Wind rises; flowers are desolate.

(Even if one tries to hold onto spring, it will not remain.

Spring goes away and people reflect quietly on their solitude.

Even if one hates the wind that scatters the flowers, it will not die down.

The petals falling as the wind blows are all the more saddening.)

And the second one (my personal preference!):

You, serene, in a house with bamboo, as the long day dwindles.

I, drunk, in a hut with flowers, watch spring leave.

(In a quiet manor house, surrounded by bamboo,

you spend this long day as spring comes to an end.

In a small house, surrounded by flowers,

I become drunk and gaze out at what little remains of spring.)

Something you’ll notice is that these both make reference to flowers. The first feels particularly significant in Episode 23, with the idea that the wind sadly blows all the blossoms away aligning with some of the other imagery in this chapter. They also share a melancholic description of the passing away of spring. We can think of spring as representing Sara in the eyes of those who care about him, and also in his eyes as the life he’s led so far – something to be missed as it imminently departs.

Other touching references to flowers come up throughout the day, like early on when Sara speaks to a lady who says the flowers are “at their very peak of beauty today” (今日が満開の美しさですわね) and at sunset when Sara laments the end of the day and an official tells him “this is when the blossoms look best” (桜が一番きれいに見える時ぞ). On the surface, these are about what is literally happening, but in the overall narrative, they’re obviously about Sara too.

And the clearest such connection comes at the start, when Sara tells us, “Today is the day I disappear” (今日は 私が散る日). He used the word 散る in Chapter 22 as well, when deciding that he would go out with a bang: “Brilliantly, colourfully, just like a flower, I will fall” (華々しく煌らかに 花のように 散ってみせよう)*. I find myself translating this word differently each time – and it does come up again after this too – because of its double meaning. On the one hand, it is literally “to fall” or “to scatter” as petals might, but it also means “to die nobly”. Sara intends to do as Yoshino no Miya advised him, and “die” so he can live again.

Sara’s repeated use of 散る in reference to himself also calls to mind his name. The sarasoju (沙羅双樹), or sal tree, or natsutsubaki (not all necessarily the same plant!) is known for its briefly blooming flowers, and is associated both with the death of the Buddha and with the opening lines of The Tale of the Heike, a story full of noble death. Frankly, I think I’d better write an entire post just about his name one of these days!

But basically, 散る is just about the most evocative way Sara could describe his departure from the Heian court. And it casts a different light on all the mentions of flowers throughout this flowery chapter!

*I particularly love this line because it feels like a twist on “Let’s live our lives heroically, let’s live them with style” (潔く、格好良く生きて行こう– the similarity is clearer in Japanese!)

Thoughts from Episode 19: Fly me to the moon

Sorry about the slow posting schedule lately! To be honest, it’ll probably continue to be quite irregular, as the actual work of translating this manga is keeping me very busy. That means I’m several chapters ahead of what I’m covering on the blog, but one upside is that writing the blog posts then lets me come back to previous chapters with a bit more distance and hopefully get a new perspective.

Anyway, Episode 19 sees the Emperor continue to give Sara extra attention, now that he’s witnessed the beauty of Sara’s sister (who actually was Sara). After an archery event, Kakumitsu takes Sara to one side to question why he’s been neglecting his wife Shi no Hime (Kakumitsu’s daughter), and Sara realises that Tsuwabuki hasn’t been spending time with her either.

Sorry about the slow posting schedule lately! To be honest, it’ll probably continue to be quite irregular, as the actual work of translating this manga is keeping me very busy. That means I’m several chapters ahead of what I’m covering on the blog, but one upside is that writing the blog posts then lets me come back to previous chapters with a bit more distance and hopefully get a new perspective.

Anyway, Episode 19 sees the Emperor continue to give Sara extra attention, now that he’s witnessed the beauty of Sara’s sister (who actually was Sara). After an archery event, Kakumitsu takes Sara to one side to question why he’s been neglecting his wife Shi no Hime (Kakumitsu’s daughter), and Sara realises that Tsuwabuki hasn’t been spending time with her either.

Sara gets Tsuwabuki and leads him away. Tsuwabuki is initially excited, until they end up visiting Shi no Hime together. During the following awkward scene, Sara and Shi no Hime seem to get along nicely, and Sara takes their daughter Yukihime away to look at the birds Shi no Hime has kept since Episode 10. He deliberately releases one of the birds, then goes off supposedly to bring it back, leaving Shi no Hime and Tsuwabuki alone to work out their… situation.

Panel from volume 4, page 145.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

The title of this chapter is “A Pair of Birds” (つがいの鳥), where つがい refers to a mated pair*. Of the four birds Shi no Hime had, one has died, leaving three left. Sara releases one of the three so it can find a mate in the wild; at the same time, he removes himself from the situation to let the lovers Shi no Hime and Tsuwabuki be together. It’s a sad bit of imagery that I found quite evocative, especially at this point:

SARA stands in the long grass, holding up his hand and looking up to the sky. The bird is flying in front of the moon and KAKUMITSU’s residence is visible in the background.

SARA [thinking] You should leave the cage behind and live by yourself.

In the outside world,

SARA turns his head thoughtfully.

SARA [thinking] maybe you can find a mate.

Meanwhile, the image of Sara walking out sadly under the moonlight at the end reminds me of some other moments in the story featuring the moon – of which there are quite a few! And this is something that also comes up a lot in the original Torikaebaya monogatari. The moonlight is often described, reminding us of something I was getting at last time, which is that life in general in the Heian court was dimly lit. Moonlit scenes stand out because it’s genuinely unusual for anything to be clearly visible at night!

The moon plays a recurring role in both literal and metaphorical forms, so just now I’ll go over a few examples of each from the manga. There are other memorable instances of characters looking forlornly at the moon: Tsuwabuki in Episode 9, Sara himself in Episode 4 and Shi no Hime in Episode 10. Watching the moon can be an enjoyable activity too, though, as we see when Sara and Shi no Hime do it together in Episode 10 and when the Emperor plans a seasonal moon viewing party in Episode 18.

References to the moon also come up as a euphemism for menstruation. Early on, Umetsubo speculates that Sara’s monthly breaks from work are evidence of tsuki no sawari, and the first sign that Shi no Hime is pregnant is that she has missed her tsuki no mono. And when Tsuwabuki and Sara do their crossdressing Yamato Takeru performance for greedy local governors in Episode 14, the lyrics feature similar lunar references.

But the reason I think the moon has symbolic significance is the way it shows up in poems. For example, I’ve already mentioned Episode 10 – which is aptly titled “A Spring Night’s Moon”. When Tsuwabuki encounters Shi no Hime in the moonlight, she recites a sad poem about how the moon reflects her emotions, and Tsuwabuki jumps in with a smooth reply (I posted translations of this pair of poems here).

The scene where Sara gazes sadly at the moon in Episode 4 is a more complicated case. There, he recites a poem (referenced again later) about how his tears should flow just as easily as Tsuwabuki’s – which comes up in a slightly different situation in the original Torikaebaya monogatari. However, this is the same scene where he first encounters Umetsubo, and at the equivalent point in the original story, he does come up with a Sad Moon Poem:

月ならば かくてすままし 雲の上を あはれいかなる 契りなるらん

I like the poem Saito chose to include here, but this one would’ve worked pretty well too! The sentiment it conveys – that he’s sad about being unable to operate at court quite like other young men – fits the scenario well.

In the manga, there’s at least one more Sad Moon Poem yet to come. Terrible events we’ve yet to cover here result in Sara being miserable in Uji, and he recites a lonely poem as he watches the moon over the river. And apart from that, there are a lot of other intriguing links to the moon throughout Torikae baya – the fact that the eclipse sees the sun (symbolising the Emperor) hidden by the moon, maybe some connection between sun/moon and yin/yang, the fact that Suiren’s name (being used by Sara as a court official) is literally “Moonlight” (月光)!

Altogether it’s far too much for me to cover here, and it’s something I need to spend more time thinking about, but perhaps I can get to that in a future post!

*The word つがい is also part of the title of Saito’s current manga series Hi no Tsugai, which continues her recent run of Heian period stories.

Thoughts from Episode 17: Remember that time when…?

I’m back after a little pause while I attended the 2025 BAJS conference last week! I enjoyed getting a chance to present on some of the interesting aspects of Saito’s adaptation, including touching on topics that I’ve explored on the blog. I also got to hear many other interesting talks about everything from Genji-inspired kimono patterns to evil smart houses. And if you happen to be reading this after having been at my talk, thank you!

Now, returning to Torikae baya, Episode 17 sees Sara go to the home of his wetnurse Aguri, filled with regret. After looking all over the capital for Sara, Tsuwabuki shows up, but Aguri throws him out once she realises that he’s involved with both Shi no Hime and Sara.

I’m back after a little pause while I attended the 2025 BAJS conference last week! I enjoyed getting a chance to present on some of the interesting aspects of Saito’s adaptation, including touching on topics that I’ve explored on the blog. I also got to hear many other interesting talks about everything from Genji-inspired kimono patterns to evil smart houses. And if you happen to be reading this after having been at my talk, thank you!

Now, returning to Torikae baya, Episode 17 sees Sara go to the home of his wetnurse Aguri, filled with regret. After looking all over the capital for Sara, Tsuwabuki shows up, but Aguri throws him out once she realises that he’s involved with both Shi no Hime and Sara.

Meanwhile at court, there are concerns about flooding of the Kamogawa during the autumn typhoons, and mockery of Togu’s efforts to help. When talk turns to Togu’s naishi no kami Suiren, old man Fujiwara (remember him? he's a priest now!) hints heavily that the Emperor should have her become one of his women – annoying both Marumitsu and Kakumitsu for separate reasons. Just as the Emperor then enquires about the absent Sara, they spot an extremely unseasonal blooming cherry branch. He sends the branch to Sara, who has been at Aguri’s house all this time sending cold replies to Tsuwabuki’s constant letters. The Emperor’s gift inspires Sara to return to the palace, and his smart suggestions earn him a new responsibility to deal with the river problem.

Sara is surprised to see Aguri handing him a blooming cherry branch with a letter.

Panel from volume 4, page 67. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

Something we see a lot of in this chapter is callbacks to moments from earlier in the story. One of these is right in the title: 野分の桜 (nowaki no sakura). Here we have the word nowaki, referring to a typhoon, particularly in the early autumn. This word came up back in Episode 12, when – during the spring – Shi no Hime compared Sara’s gentle demeanour to spring sunlight and Tsuwabuki’s passion to a nowaki. The title of Episode 17 once again juxtaposes nowaki with an image of spring, but the out-of-season reference is reversed: while Tsuwabuki was like a nowaki in spring, the Emperor sends Sara a blooming cherry branch in autumn.

Incidentally, this chapter title was a bit of a tricky one to translate. I would expect readers to know what a typhoon is, but it’s relevant to the setting (and the callback to Episode 12) that the title uses a more archaic term that’s specifically associated with autumn. And that’s a lot of information to try and convey when the original title is very short in Japanese – especially if you opt for “cherry blossom” which is already two words. The translation I’ve ended up with, at least for now, is “Autumn Blooms”. This actually omits both of the specific nouns to emphasise the seasonal contrast instead, but I like that it’s short and that it can be read both as modifier-noun (meaning “blooms in autumn”) or as noun-verb (meaning “autumn is blooming”).

Another callback comes in the message the Emperor sends along with the branch. He sends the miraculous unseasonal flowers to Sara, whom he says “waits on a miracle”. This calls back to Episode 15, where the Emperor refers all the way back to Episode 3. He remembers that Sara went to confront the eclipse in order to break a curse, and that according to Sara, the curse has still not been lifted. This has the effect of reminding readers of the tengu’s curse that supposedly afflicts Sara – and in the story, it acts as encouragement to Sara to take control of his life instead of waiting for fate to take its course.

And one last point I want to bring up is the poems that Sara and Tsuwabuki exchange by letter. As I discussed several weeks ago, there are many poems in the manga that come directly from the original Torikaebaya monogatari. Here, there are several poems from the equivalent point in the original story, with Tsuwabuki insisting that he’s so worried he could die, and Sara questioning his seriousness. Finally, just like his counterpart in Torikaebaya monogatari, Sara sends this poem:

まして思え 世に類なき身の 憂さに 嘆き乱るる ほどの心を

(私の心のことも少しは考えてみてください 世に例のない身になった辛さに嘆き乱れる私の心も)

The wording calls back to one of the poems I mentioned in that earlier post, where Sara expresses his sadness to Tsuwabuki in Episode 4. In that poem, he says that he suffers in a way that can’t compare to others, and in my translation I used the phrase “my singularly wretched existence”. So of course, wanting to reflect this reference, I included that phrase again when translating the Episode 17 poem:

"Consider something worse: a singularly wretched existence and a heart wracked with woe."

(Think for a moment about how it feels for me. In my heart, I constantly lament the pain of being unlike anyone else in the world.)

Given the way that these two poems link to each other in the original story, it makes sense that Saito wanted to preserve them both in the adaptation – and I hope I made that connection clear too!

More thoughts from Episode 13: Yume no Wada

Like I said in the previous post, Episode 13 is one of two chapters that I initially translated a year ago, and that means I’ve had time to think about it a bit more than some of the others. On that note, I’d like to write about it some more, and use an example from Episode 13 to return to a topic from another earlier blog post: poetry!

Like I said in the previous post, Episode 13 is one of two chapters that I initially translated a year ago, and that means I’ve had time to think about it a bit more than some of the others. On that note, I’d like to write about it some more, and use an example from Episode 13 to return to a topic from another earlier blog post: poetry!

One of the things that’s so interesting about Torikae baya is that it doesn’t always directly follow the source material, but includes adjustments and additions to the story. Many of the additions serve to give more detail to the world by giving readers a sense of what life in the capital was like in the Heian period, such as by showing various annual ceremonies. There are also references to other works of classical literature, from the Heian period or earlier.

In that earlier post about poetry, I talked about how important writing and sharing poetry was in Heian court culture and how Saito features some of the exact poems that appear in the original Torikaebaya monogatari, but not all of them come from there. And rather than attempt to produce poetry in classical language herself, Saito includes poems from other classical sources.

Panel from volume 3, page 79.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

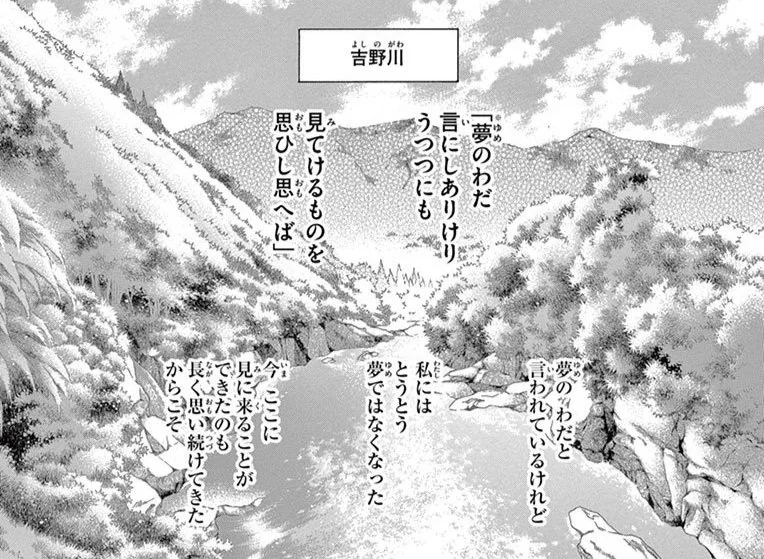

At the beginning of Episode 13, Togu and her entourage reach Yoshino, and the chapter opens with her looking out upon a body of water where two rivers, the Yoshinogawa and Kisadanigawa, meet. She then appears to recite a poem, shown first in classical Japanese, and then followed by an explanatory modern Japanese version:

夢のわだ 言にしありけり うつつにも 見てけるものを 思ひし思へば

(夢のわだと言われているけれど 私にはとうとう夢ではなくなった 今ここに見にくることができたのも長く思い続けてきたからこそ)

This poem comes from the Man’yoshu, one of the most significant poetry anthologies in Japan, which was compiled by some time in the Nara period (710-794 CE). That means that we aren’t expected to imagine that Togu just came up with this by herself, but that she too is referring to well-known existing literature. It’s a very apt poem for her situation, as it is about the place she’s visiting! Yume no Wada (which translates roughly to “pool/ravine of dreams”) is a name for this location, and in the poem, the narrator shares the feeling of finally seeing it for themselves after having wanted to for a long time.

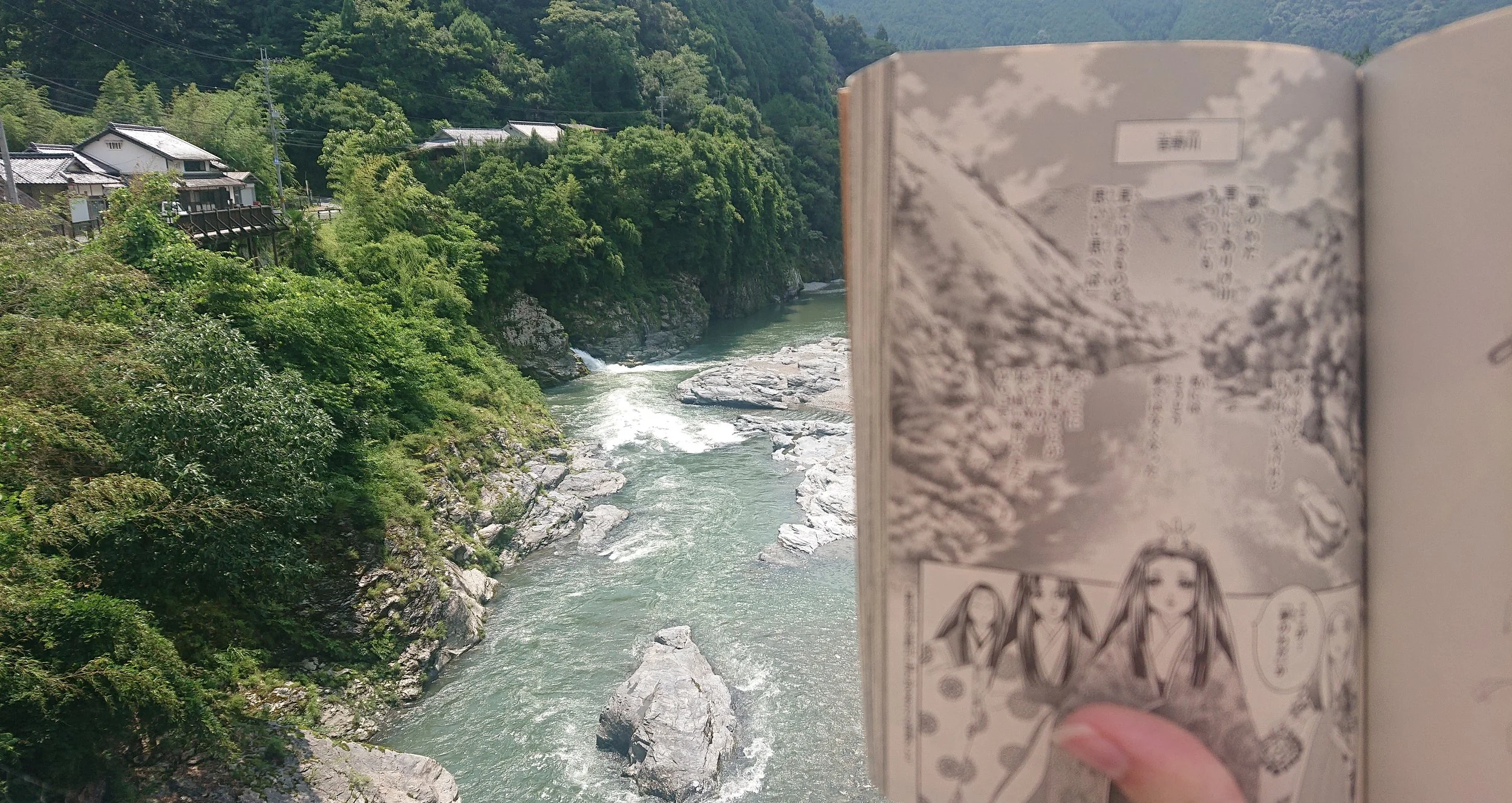

When I first tried translating this, I had to rely heavily on the modern Japanese version provided as well as other modern glosses and explanations available (like this one and this one). But I can now approach it a bit differently, as I’ve recently been in Japan studying classical Japanese (kobun) and visiting locations including Yume no Wada!

Learning how to read classical Japanese obviously helped me to understand poems like this one. I should point out that since “classical Japanese” refers mainly to the language as used in the Heian period, there are aspects of Nara period usage that are different from what I studied – this might be why there are expressions in the poem I can’t just conveniently find in my classical dictionary! Still, being able to analyse a poem like this and at least work out which parts require additional research makes the task much more realistic.

And going there in person was also helpful! At first, I had “wada” down as “cove”, because even with dictionary entries and the detailed image in the manga, it was hard for me to quite understand the nature of this bit of water. From seeing it for myself, I understand that the Kisadanigawa is much narrower than the Yoshinogawa, and that where the narrow part feeds into the wider river, it forms this slower-moving patch of water.

And so, armed with this knowledge, I feel better able to do justice to this interesting use of additional literary references! Here is my current translation:

“Yume no Wada” / is but a name. / Wide awake, / I have now seen it, / just as I long dreamt.

(They call it the Pool of Dreams, but it is not merely a dream to me any longer. I have finally come to see it for myself, all because I desired to for so long.)

I like to think that now that I know more and I’ve given it some deeper thought, I’ve come up with a decent translation. Something that was actually quite handy about rendering this in English is that “dream” can be used to mean “long for [something]”, letting me incorporate the poem’s contrast between dreams and reality in a slightly different way that meant I could keep the order of information the same as in the original poem. Meanwhile, having the lengthier modern version as an opportunity to go into more detail about the meaning allowed me to stick to something brief and abstract for the poem itself.

And of course, it wasn’t lost on me that making a pilgrimage to the spot where Togu cites the poem about finally seeing the “pool of dreams” in real life doubled up on the original reference. So to commemorate the dream-versus-reality within a dream-versus-reality, I also recited the poem and took a picture of the manga page next to its real-world counterpart!

Thoughts from Episode 11: “Words mean nothing”

Back to a more typical post this week, looking at Episode 11 and then getting into a bit of poetry!

This chapter begins right as the last one left off, with Tsuwabuki approaching Shi no Hime. It’s not long before he has his way with her, learning in the process that her husband Sara hasn’t – much to his surprise and confusion. As he leaves in the morning, eager to visit again, Shi no Hime’s attendant Saemon takes pity on Tsuwabuki and continues to exchange letters with him.

Back to a more typical post this week, looking at Episode 11 and then getting into a bit of poetry!

This chapter begins right as the last one left off, with Tsuwabuki approaching Shi no Hime. It’s not long before he has his way with her, learning in the process that her husband Sara hasn’t – much to his surprise and confusion. As he leaves in the morning, eager to visit again, Shi no Hime’s attendant Saemon takes pity on Tsuwabuki and continues to exchange letters with him.

After all that, Shi no Hime stays in bed and is too ashamed to speak to Sara when he gets home. Though he can’t figure out what the problem is, Sara takes time off from work to look after her. When he returns to work, he is told that Tsuwabuki has also been missing, but when he tries to pay him a visit, Tsuwabuki won’t see him. This is because he is also ashamed, but not so ashamed that he’ll give up on Shi no Hime. Soon afterwards, Shi no Hime finds out that Tsuwabuki has been writing letters, and decides to invite him round to break up with him, but… let’s just say that doesn’t work…

If you’re wondering what today’s title is all about, “Words mean nothing” is the smooth line Tsuwabuki says to Shi no Hime at the end of this chapter (originally 言葉なぞ無意味). Of course, it does make sense in context, but there’s something quite ironic about this line considering the prominent use of poetry in Tsuwabuki’s attempts to woo Shi no Hime. And this is an aspect where, in Torikae baya, Saito directly incorporates some of the original text of Torikaebaya monogatari!

First, it’s worth mentioning that poetry was a big deal for the people of the Heian court. For someone to matter in that world, they were expected to be both knowledgeable and skilled when it came to poetry. There were all sorts of situations where people of the court would write and recite poetry, and we get a little sense of that throughout the early chapters of Torikae baya. An early sign of Sara’s affinity for boys’ activities is when he offers to show a visitor, Captain Emon, a poem that he has written. As times goes by, we also get a sense of how important poetry is for romance: Tsuwabuki’s friend Minamoto no Tadasuke shares a sad story about how he sent a poem to a girl he liked, only for her to send it back with corrections; Tsuwabuki pesters Sara to let him send poems to Suiren; and Sara kicks off marriage proceedings with Shi no Hime by writing her a poem.

So far in Torikae baya, five poems have been quoted directly from the original story, accompanied each time by a modern Japanese translation/explanation (remember that Torikaebaya monogatari is from the late Heian period, probably the 1100s). I won’t go into much detail on all of them, but I’ll at least share them all here! The first is in Episode 4, when Sara attempts to convince Tsuwabuki to give up on getting to know his sister. He says (original* first, Saito’s modern Japanese version second):

たぐいなき 憂き身と思い 知るからに さやは涙の 浮きて流るる

(世に類のない生き辛い我が身と思い知ってるから そんな私でさえそんなふうに涙を流したりしないのに)

In this scene, Sara tries to reject Tsuwabuki’s friendship entirely. Ruled by passion as always, Tsuwabuki begins to cry, and Sara’s poem laments that though he himself has so much to worry about, he can’t bring himself to cry as easily as Tsuwabuki. This poem highlights the differences in personality between Sara and Tsuwabuki – and indeed, between their counterparts in Torikaebaya monogatari. Including it in the manga makes the moment stand out and really feel like an instance where Sara is unable to contain his melancholy.

The next quoted poem comes from Sara again, when he writes to Shi no Hime in Episode 6:

これやさは 入りて繁きは 道ならむ 山口しるく 惑はるるかな

(これが人のいう恋路の山でしょうか? 早くもほんの入り口で心乱れている私です)

Next, a pair of poems are taken from Torikaebaya monogatari. This is in the Episode 10 scene where Tsuwabuki, being weird about Sara’s coat, overhears Shi no Hime playing the koto and reciting poetry. Shi no Hime says:

春の夜も 見る我からの 月なれば 心づくしの 影となりけり

(明るい春の夜も見る者それぞれの感じる月だから 暗い心の私には月も暗いように感じられる)

What I’ve been doing with these poems so far is taking advantage of there being two of them, by writing a first translation that is shorter and more abstract, and a second one that elaborates a bit more on the poem’s implications. Either way, I’ve been relying quite heavily on the modern Japanese versions (and other modern Japanese versions besides the manga) because of my limited experience with classical Japanese, but that’s all changing as we speak! With funding from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation, I’m on a summer course for classical Japanese right now, so I’m hoping to come back to these poems and do a much better job later.

But for now, you probably want to know about Shi no Hime’s poem, so I will give you what I’ve written in the current draft:

On a spring's night, the moon is still that of its viewer. My heart's disquiet is reflected therein.

(Even on a bright night in spring, the moon feels different for each person. So when I feel gloomy inside, the moon is gloomy too.)

Now, as I said, this is the first in a pair of poems, both drawn from the original Torikaebaya monogatari. The second in the pair comes from Tsuwabuki. He has heard Shi no Hime’s forlorn poem and concludes both that she understands his feelings and that she must be unhappy with her marriage. Because he always had a thing for Shi no Hime, he decides that this is his big chance, so he responds:

忘られぬ 心や月に 通ふらむ 心づくしの 影と見けるは

(あなたを忘れられない私の心が月に通じたのでしょうか あなたが月を暗いように感じたのは)

And here is what I have at the moment:

My unforgetting heart must have touched the moon, if you see a reflection of your heart's disquiet.

(I could never forget you. Perhaps those feelings of mine affected the moon, if you feel that it is gloomy.)

I’ll leave it for you to decide whether these translations are up to scratch, but hopefully you can at least see how they communicate with one another! Not every poem from the original makes its way into the manga, so again, the inclusion of these poems does a lot to help the scene stand out. It feels like a big moment, and one where perhaps it would be a disservice to the story to try and convey it through means other than poetry.

And finally, for the sake of completion, here is the poem that comes up in this week’s chapter. Tsuwabuki, who now feels like Shi no Hime was always the one for him, recites this poem right before he leaves her in the morning:

我がために えに深ければ 三瀬川 のちの逢瀬も 誰かたづねむ

(女は初めての男に背負われて渡ると言われる三途の川 あなたを背負うのは私ですよ それほどあなたと私の縁は深いのです だからどうやって逢瀬を重ねたらよいか教えてください)

You’ll likely notice that the modern Japanese version is significantly longer this time, mainly because it requires an explanation of stories about the Sanzu River. But at this point, I’ve already gone on more than long enough, so I’ll leave it there – but you can expect to hear more about poetry very soon!

*There is a bit of variation in the orthography, so some of these might have been made slightly easier for today’s readers, but the words themselves are as they were in the original text.