Blogging about my Torikae baya manga translation project.

Thoughts from Episode 14: Location, location, location

Thanks to a bright idea from Suiren, Sara and Tsuwabuki are sent off on a months-long expedition to get regional governors to release their hoarded rice. It turns out their strategy is to dazzle the governors with a performance based on the legend of Yamato Takeru, before pulling out their swords and threatening them.

Thanks to a bright idea from Suiren, Sara and Tsuwabuki are sent off on a months-long expedition to get regional governors to release their hoarded rice. It turns out their strategy is to dazzle the governors with a performance based on the legend of Yamato Takeru, before pulling out their swords and threatening them.

One night later in the trip, Shikibu-kyo no Miya is awaiting the two of them. He flirts aggressively with Sara, leading Tsuwabuki to step in to take one for the team, but just as things start to heat up, Sara returns the favour and saves Tsuwabuki from an inevitable gay awakening. Sara tells Tsuwabuki he’s a great friend he never should’ve doubted, but when he returns to Heian-kyo just after Shi no Hime gives birth, he realises his newborn daughter looks a lot like his loyal buddy.

There’s a lot that could be said about this chapter, but the thing I want to focus on today is locations! After a long period where nearly all the action takes place in the capital, Episodes 13 and 14 both see the protagonists go further afield. In Episode 13, they visit Yoshino, and in this chapter, Sara and Tsuwabuki travel around quite a bit.

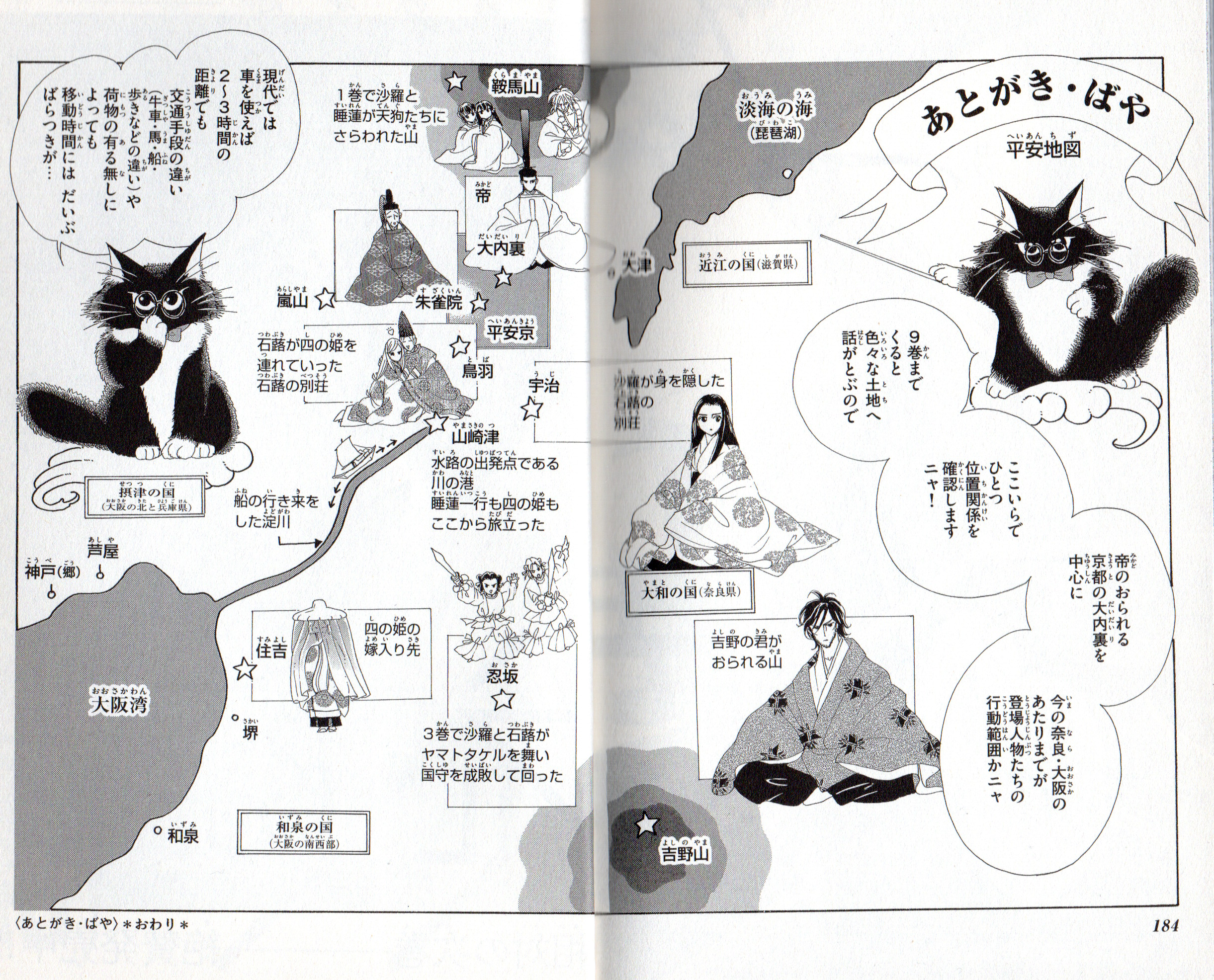

Map from volume 9, pages 184 and 185.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

The only named place they visit in Episode 14 is Osaka – that’s 忍坂 with a short “o”, not the more famous 大阪 with a long “o”. The place that appears in Torikae baya is in modern-day Nara Prefecture, whereas the big city of Osaka we know today didn’t exist with that name until a few hundred years later. Incidentally, another more famous “Osaka” in the Heian period was 逢坂 (also a long “o”), an important barrier on the route from Heian-kyo to the eastern provinces, which appears in a number of poems.

Now, as you may have gleaned from my previous post where I talked about checking out locations from the manga in person, places in Torikae baya are often portrayed in quite specific detail. Places like palace buildings are clearly drawn based on real-life counterparts, and Saito uses some of the afterwords in each volume to provide plans of Heian-kyo and the palace. For the latter, she points out that she made a few adjustments to the exact layout compared with what the real Heian court was like, but just having it drawn up is really helpful for understanding how everything comes together.

One afterword also features a map of the whole relevant area, showing locations like Kurama and Yoshino – and since it’s in volume 9, there are also other places from much later in the story. A nice thing about this map is that Saito gives a little explanation of how people got around the area and how long it took. Typical means of transport included boat, horse, ox-drawn cart or walking, and even using the fastest of these, a trip that would take a few hours today might have required a day’s travel or more at the time of Torikae baya.

A couple of months ago, I added the Extras page as a place for the series timeline (which is still getting semi-regular updates!), and now I’ve added a map there too. You can then click through to a Google map where you can see where these historical locations line up with modern-day geography. I’ve tried to include all specified locations from the manga, but as there are probably some later ones that I can’t remember right now, you might see some updates to this as well. Please check it out!

Digression: Research trip report

Something different this week! I’ve hinted in previous posts that I’ve been on a trip in Japan over the summer, and now that I’m finally back, I want to talk about what happened.

The main purpose of the research trip – which I managed to do with funding from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation, the Japan Foundation Endowment Committee and the School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures at the University of Edinburgh – was to take part in a summer school programme for classical Japanese at Doshisha University in Kyoto. Over six weeks and a bit, I learnt the basics of classical Japanese (kobun) and how to understand texts. While I was there, I also took the chance to visit some of the locations from Torikae baya and – very excitingly!! – I went to Tokyo and spoke to Saito Chiho in person about the manga.

Something different this week! I’ve hinted in previous posts that I’ve been on a trip in Japan over the summer, and now that I’m finally back, I want to talk about what happened.

The main purpose of the research trip – which I managed to do with funding from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation, the Japan Foundation Endowment Committee and the School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures at the University of Edinburgh – was to take part in a summer school programme for classical Japanese at Doshisha University in Kyoto. Over six weeks and a bit, I learnt the basics of classical Japanese (kobun) and how to understand texts. While I was there, I also took the chance to visit some of the locations from Torikae baya and – very excitingly!! – I went to Tokyo and spoke to Saito Chiho in person about the manga.

First, the course. For about three hours each weekday morning, we spent the first week or two going through all the main grammar points in Shirane’s Classical Japanese: A Grammar. It’s a pretty dry book, but there isn’t really any way around reading over and memorising all the conjugations and auxiliary verbs and particles, and I think this textbook handles it all pretty comprehensively! And even though this intensive approach was a lot of hard work and effort, it meant we could fairly quickly move on and start practicing applying what we’d covered by looking at original texts.

Classical Japanese is very different from modern Japanese. A lot of the words resemble ones we know now, but they might behave differently, or have different meanings. Plus, there are words for things that we just don’t have in the modern world. A lot of the conjugation rules in modern Japanese evolved as the sounds or uses of older patterns changed with time, sometimes frustratingly turning into things that look a lot like different older rules (I’m convinced that in whatever form Japanese takes in the future, there will be a whole new set of unrelated structures that all abbreviate to ん). But once you start getting the hang of the old rules, then you can start breaking it all down and trying to understand. And you know, it does actually get easier with practice!

In the last post, I gave an example of a part in Torikae baya that I’ve now been able to retranslate with better understanding of how to approach classical quotations. I’m looking forward to applying this knowledge elsewhere too, to translate poems like these better, but also to take a look at the original text and see for myself where different interpretations come from.

In between studying, buying things to take home and seeing an all-women Castlevania musical, I found time to seek out some of the locations that appear in the manga. The places in Torikae baya are often depicted in very specific detail, and I was keen to see some of them for myself and get a sense of where things are and what they’re like.

I went to Kurama, where Sara and Suiren get kidnapped by the “tengu” bandits in Episode 1. The main attraction is the temple, but if you keep walking up the mountain, you reach an area where gnarled tree roots are exposed above the ground. It’s very striking, and that’s probably why Saito put it in the manga! After Sara and Suiren run away from the gang, this is where Marumitsu finds them sleeping in the morning.

Trees in Kurama.

Marumitsu finds Sara and Suiren.

Panel from volume 1, page 33. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

Conveniently, the university and my accommodation were both near the old Imperial Palace, which is easier to visit than I think it used to be. Buildings here serve as models for their counterparts in Torikae baya, including the Shishinden and the Seiryoden.

The current Shishinden at the Imperial Palace in Kyoto.

The Shishinden as it appears in the manga.

Panel from volume 1, page 116. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

Yoshino is another major location in Torikae baya. I’ve been there a few times before, but always to Yoshinoyama, the mountain itself, so I hadn’t seen it quite as it appears in the manga. By visiting the area around Yume no Wada this time, I understood that the palace they go to must be this one, and that Sara and Suiren’s search for fireflies probably takes them along the Kisadanigawa and up the mountain from the east side, not at all the route that visitors take to Yoshinoyama nowadays. I also happened to go there at about the same time of year as Episode 13 in the manga – I didn’t spot any fireflies, but I suppose they didn’t either in the end!

Part of a notice board at the excavation site of the Miyataki Ruins in Yoshino.

The palace at Yoshino in the manga.

Panel from volume 3, page 80. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

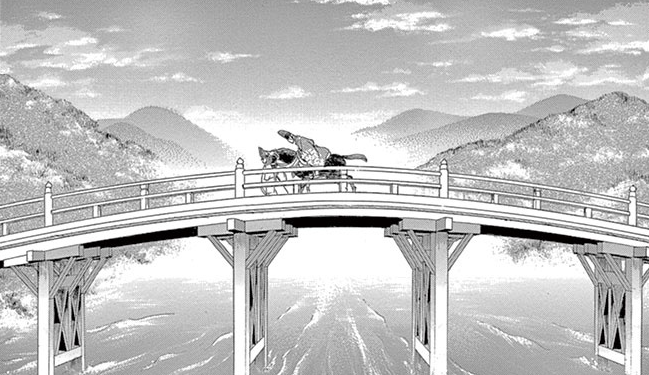

The class took a field trip to Uji, mainly because of its connection to the Tale of Genji, but it is also a location a bit later in Torikae baya, particularly around the Ujibashi, a bridge that has various historical and literary claims to fame (though it has been rebuilt many times and the current one is really quite new). The nearby Tale of Genji Museum also has some useful information about customs and architecture of the Heian period.

The current Ujibashi.

Tsuwabuki crossing the Ujibashi.

Panel from volume 6, page 155. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

Getting to see these places for myself was fun, but informative too! I got a clearer sense of scale and distance, which helped me understand some of the manga scenes better. For example, you get a very strong sense of the danger Sara and Suiren face in Episode 1 when you realise they have to flee uphill to such a remote hiding place on the mountain. There’s no guarantee that their father would find them before the bandits do – if at all.

Besides these specific locations, I also visited places like Torin’in, a temple known for sarasoju flowers, and the Kyoto International Manga Museum. All in all, it was good just to have the chance to stay for an extended period right in the middle of where Torikae baya takes place!

And last but not least, I was lucky enough to get to interview Saito Chiho herself! Though there is a bit of information available about how she approached writing Torikae baya in a few magazine interviews and the afterwords that appear in each manga volume, I was interested to learn more about the process, her sources, etc. During our interview, I heard about how much background research was involved and how she wanted to show the near-constant annual cycle of ceremonies in the Heian court. I got a strong sense that making the story feel more positive (not that everything is exactly happy in the manga, but in contrast with the quite austere and fatalistic Buddhist messaging of the source material) was a key factor in the adjustments she made in the adaptation.

I also got to see her workroom and take a look at the many books that informed the adaptation. Besides different versions of Torikaebaya monogatari, there was a lot about Heian period customs, beliefs and – of course – clothes. Afterwards, I even managed to find copies of a couple of the books she showed me! It was a really exciting opportunity, and I learnt a lot and got plenty of motivation from it too.

And so that’s what I’ve been up to for the past couple of months! It’s been so busy that the main translation work has slowed down a bit, but now that I’m home, I’ll get back on track and hopefully be able to do a better job with everything I’ve learnt since!