Blogging about my Torikae baya manga translation project.

Thoughts from Episode 14: Location, location, location

Thanks to a bright idea from Suiren, Sara and Tsuwabuki are sent off on a months-long expedition to get regional governors to release their hoarded rice. It turns out their strategy is to dazzle the governors with a performance based on the legend of Yamato Takeru, before pulling out their swords and threatening them.

Thanks to a bright idea from Suiren, Sara and Tsuwabuki are sent off on a months-long expedition to get regional governors to release their hoarded rice. It turns out their strategy is to dazzle the governors with a performance based on the legend of Yamato Takeru, before pulling out their swords and threatening them.

One night later in the trip, Shikibu-kyo no Miya is awaiting the two of them. He flirts aggressively with Sara, leading Tsuwabuki to step in to take one for the team, but just as things start to heat up, Sara returns the favour and saves Tsuwabuki from an inevitable gay awakening. Sara tells Tsuwabuki he’s a great friend he never should’ve doubted, but when he returns to Heian-kyo just after Shi no Hime gives birth, he realises his newborn daughter looks a lot like his loyal buddy.

There’s a lot that could be said about this chapter, but the thing I want to focus on today is locations! After a long period where nearly all the action takes place in the capital, Episodes 13 and 14 both see the protagonists go further afield. In Episode 13, they visit Yoshino, and in this chapter, Sara and Tsuwabuki travel around quite a bit.

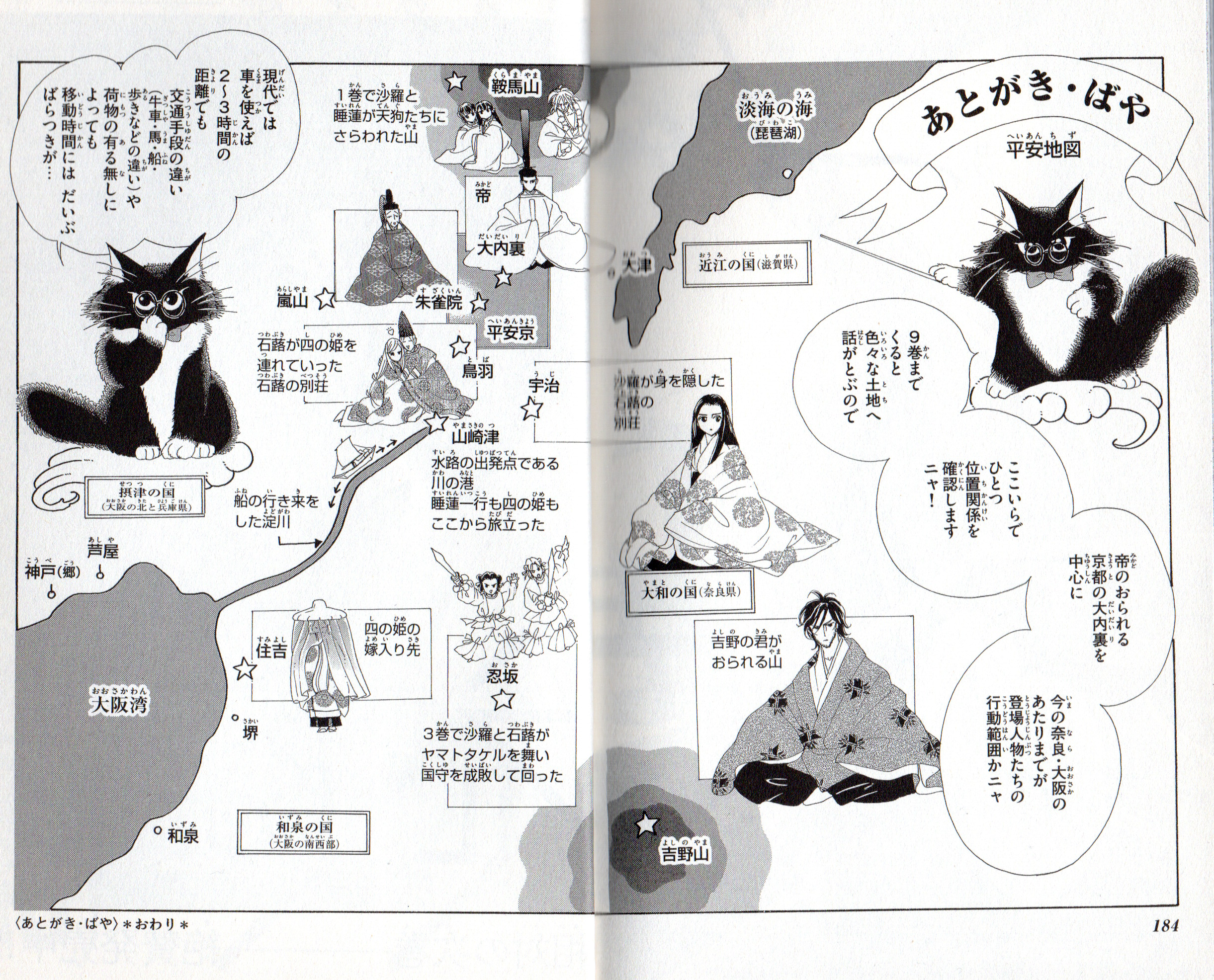

Map from volume 9, pages 184 and 185.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

The only named place they visit in Episode 14 is Osaka – that’s 忍坂 with a short “o”, not the more famous 大阪 with a long “o”. The place that appears in Torikae baya is in modern-day Nara Prefecture, whereas the big city of Osaka we know today didn’t exist with that name until a few hundred years later. Incidentally, another more famous “Osaka” in the Heian period was 逢坂 (also a long “o”), an important barrier on the route from Heian-kyo to the eastern provinces, which appears in a number of poems.

Now, as you may have gleaned from my previous post where I talked about checking out locations from the manga in person, places in Torikae baya are often portrayed in quite specific detail. Places like palace buildings are clearly drawn based on real-life counterparts, and Saito uses some of the afterwords in each volume to provide plans of Heian-kyo and the palace. For the latter, she points out that she made a few adjustments to the exact layout compared with what the real Heian court was like, but just having it drawn up is really helpful for understanding how everything comes together.

One afterword also features a map of the whole relevant area, showing locations like Kurama and Yoshino – and since it’s in volume 9, there are also other places from much later in the story. A nice thing about this map is that Saito gives a little explanation of how people got around the area and how long it took. Typical means of transport included boat, horse, ox-drawn cart or walking, and even using the fastest of these, a trip that would take a few hours today might have required a day’s travel or more at the time of Torikae baya.

A couple of months ago, I added the Extras page as a place for the series timeline (which is still getting semi-regular updates!), and now I’ve added a map there too. You can then click through to a Google map where you can see where these historical locations line up with modern-day geography. I’ve tried to include all specified locations from the manga, but as there are probably some later ones that I can’t remember right now, you might see some updates to this as well. Please check it out!

Digression: Research trip report

Something different this week! I’ve hinted in previous posts that I’ve been on a trip in Japan over the summer, and now that I’m finally back, I want to talk about what happened.

The main purpose of the research trip – which I managed to do with funding from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation, the Japan Foundation Endowment Committee and the School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures at the University of Edinburgh – was to take part in a summer school programme for classical Japanese at Doshisha University in Kyoto. Over six weeks and a bit, I learnt the basics of classical Japanese (kobun) and how to understand texts. While I was there, I also took the chance to visit some of the locations from Torikae baya and – very excitingly!! – I went to Tokyo and spoke to Saito Chiho in person about the manga.

Something different this week! I’ve hinted in previous posts that I’ve been on a trip in Japan over the summer, and now that I’m finally back, I want to talk about what happened.

The main purpose of the research trip – which I managed to do with funding from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation, the Japan Foundation Endowment Committee and the School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures at the University of Edinburgh – was to take part in a summer school programme for classical Japanese at Doshisha University in Kyoto. Over six weeks and a bit, I learnt the basics of classical Japanese (kobun) and how to understand texts. While I was there, I also took the chance to visit some of the locations from Torikae baya and – very excitingly!! – I went to Tokyo and spoke to Saito Chiho in person about the manga.

First, the course. For about three hours each weekday morning, we spent the first week or two going through all the main grammar points in Shirane’s Classical Japanese: A Grammar. It’s a pretty dry book, but there isn’t really any way around reading over and memorising all the conjugations and auxiliary verbs and particles, and I think this textbook handles it all pretty comprehensively! And even though this intensive approach was a lot of hard work and effort, it meant we could fairly quickly move on and start practicing applying what we’d covered by looking at original texts.

Classical Japanese is very different from modern Japanese. A lot of the words resemble ones we know now, but they might behave differently, or have different meanings. Plus, there are words for things that we just don’t have in the modern world. A lot of the conjugation rules in modern Japanese evolved as the sounds or uses of older patterns changed with time, sometimes frustratingly turning into things that look a lot like different older rules (I’m convinced that in whatever form Japanese takes in the future, there will be a whole new set of unrelated structures that all abbreviate to ん). But once you start getting the hang of the old rules, then you can start breaking it all down and trying to understand. And you know, it does actually get easier with practice!

In the last post, I gave an example of a part in Torikae baya that I’ve now been able to retranslate with better understanding of how to approach classical quotations. I’m looking forward to applying this knowledge elsewhere too, to translate poems like these better, but also to take a look at the original text and see for myself where different interpretations come from.

In between studying, buying things to take home and seeing an all-women Castlevania musical, I found time to seek out some of the locations that appear in the manga. The places in Torikae baya are often depicted in very specific detail, and I was keen to see some of them for myself and get a sense of where things are and what they’re like.

I went to Kurama, where Sara and Suiren get kidnapped by the “tengu” bandits in Episode 1. The main attraction is the temple, but if you keep walking up the mountain, you reach an area where gnarled tree roots are exposed above the ground. It’s very striking, and that’s probably why Saito put it in the manga! After Sara and Suiren run away from the gang, this is where Marumitsu finds them sleeping in the morning.

Trees in Kurama.

Marumitsu finds Sara and Suiren.

Panel from volume 1, page 33. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

Conveniently, the university and my accommodation were both near the old Imperial Palace, which is easier to visit than I think it used to be. Buildings here serve as models for their counterparts in Torikae baya, including the Shishinden and the Seiryoden.

The current Shishinden at the Imperial Palace in Kyoto.

The Shishinden as it appears in the manga.

Panel from volume 1, page 116. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

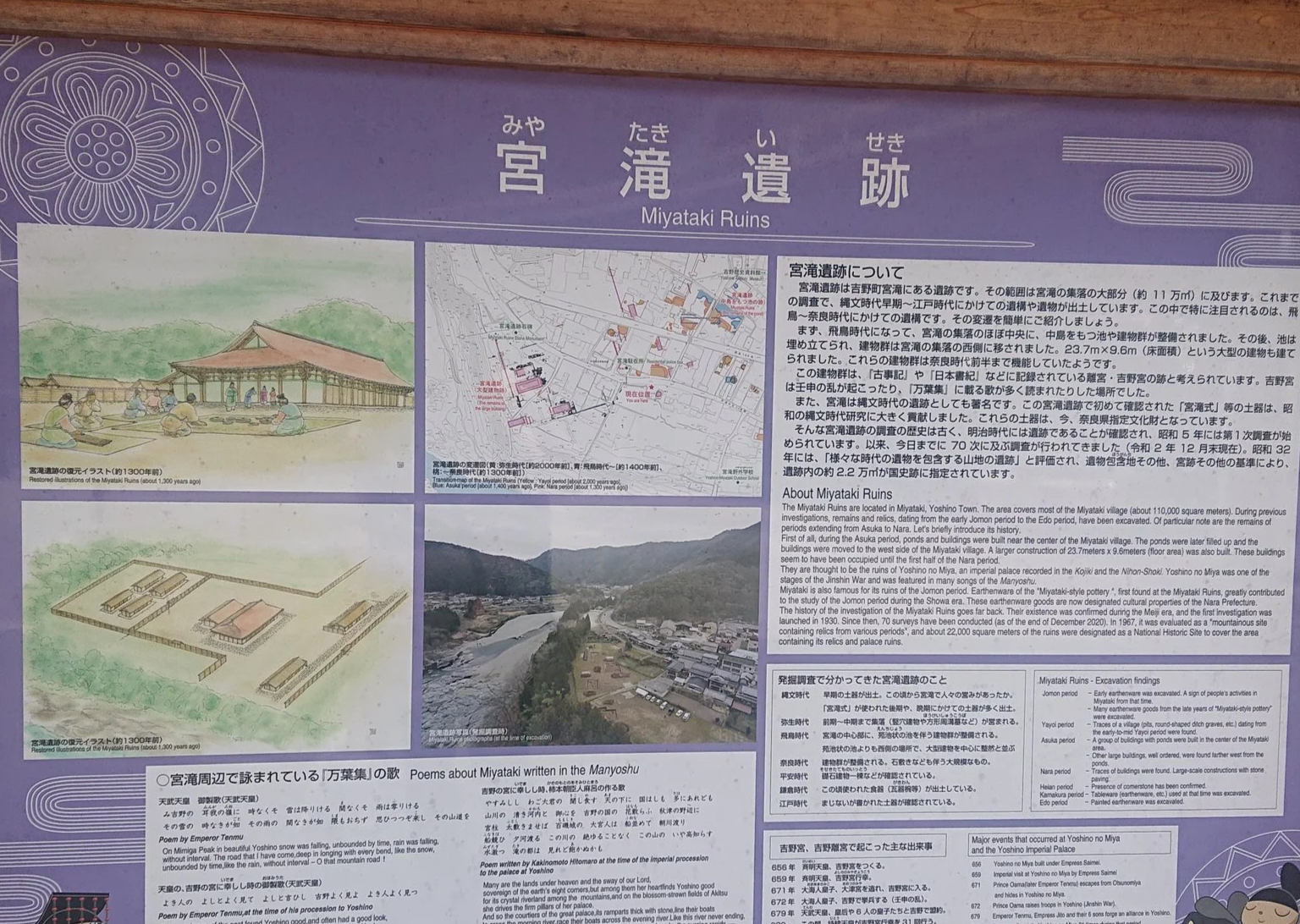

Yoshino is another major location in Torikae baya. I’ve been there a few times before, but always to Yoshinoyama, the mountain itself, so I hadn’t seen it quite as it appears in the manga. By visiting the area around Yume no Wada this time, I understood that the palace they go to must be this one, and that Sara and Suiren’s search for fireflies probably takes them along the Kisadanigawa and up the mountain from the east side, not at all the route that visitors take to Yoshinoyama nowadays. I also happened to go there at about the same time of year as Episode 13 in the manga – I didn’t spot any fireflies, but I suppose they didn’t either in the end!

Part of a notice board at the excavation site of the Miyataki Ruins in Yoshino.

The palace at Yoshino in the manga.

Panel from volume 3, page 80. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

The class took a field trip to Uji, mainly because of its connection to the Tale of Genji, but it is also a location a bit later in Torikae baya, particularly around the Ujibashi, a bridge that has various historical and literary claims to fame (though it has been rebuilt many times and the current one is really quite new). The nearby Tale of Genji Museum also has some useful information about customs and architecture of the Heian period.

The current Ujibashi.

Tsuwabuki crossing the Ujibashi.

Panel from volume 6, page 155. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

Getting to see these places for myself was fun, but informative too! I got a clearer sense of scale and distance, which helped me understand some of the manga scenes better. For example, you get a very strong sense of the danger Sara and Suiren face in Episode 1 when you realise they have to flee uphill to such a remote hiding place on the mountain. There’s no guarantee that their father would find them before the bandits do – if at all.

Besides these specific locations, I also visited places like Torin’in, a temple known for sarasoju flowers, and the Kyoto International Manga Museum. All in all, it was good just to have the chance to stay for an extended period right in the middle of where Torikae baya takes place!

And last but not least, I was lucky enough to get to interview Saito Chiho herself! Though there is a bit of information available about how she approached writing Torikae baya in a few magazine interviews and the afterwords that appear in each manga volume, I was interested to learn more about the process, her sources, etc. During our interview, I heard about how much background research was involved and how she wanted to show the near-constant annual cycle of ceremonies in the Heian court. I got a strong sense that making the story feel more positive (not that everything is exactly happy in the manga, but in contrast with the quite austere and fatalistic Buddhist messaging of the source material) was a key factor in the adjustments she made in the adaptation.

I also got to see her workroom and take a look at the many books that informed the adaptation. Besides different versions of Torikaebaya monogatari, there was a lot about Heian period customs, beliefs and – of course – clothes. Afterwards, I even managed to find copies of a couple of the books she showed me! It was a really exciting opportunity, and I learnt a lot and got plenty of motivation from it too.

And so that’s what I’ve been up to for the past couple of months! It’s been so busy that the main translation work has slowed down a bit, but now that I’m home, I’ll get back on track and hopefully be able to do a better job with everything I’ve learnt since!

More thoughts from Episode 13: Yume no Wada

Like I said in the previous post, Episode 13 is one of two chapters that I initially translated a year ago, and that means I’ve had time to think about it a bit more than some of the others. On that note, I’d like to write about it some more, and use an example from Episode 13 to return to a topic from another earlier blog post: poetry!

Like I said in the previous post, Episode 13 is one of two chapters that I initially translated a year ago, and that means I’ve had time to think about it a bit more than some of the others. On that note, I’d like to write about it some more, and use an example from Episode 13 to return to a topic from another earlier blog post: poetry!

One of the things that’s so interesting about Torikae baya is that it doesn’t always directly follow the source material, but includes adjustments and additions to the story. Many of the additions serve to give more detail to the world by giving readers a sense of what life in the capital was like in the Heian period, such as by showing various annual ceremonies. There are also references to other works of classical literature, from the Heian period or earlier.

In that earlier post about poetry, I talked about how important writing and sharing poetry was in Heian court culture and how Saito features some of the exact poems that appear in the original Torikaebaya monogatari, but not all of them come from there. And rather than attempt to produce poetry in classical language herself, Saito includes poems from other classical sources.

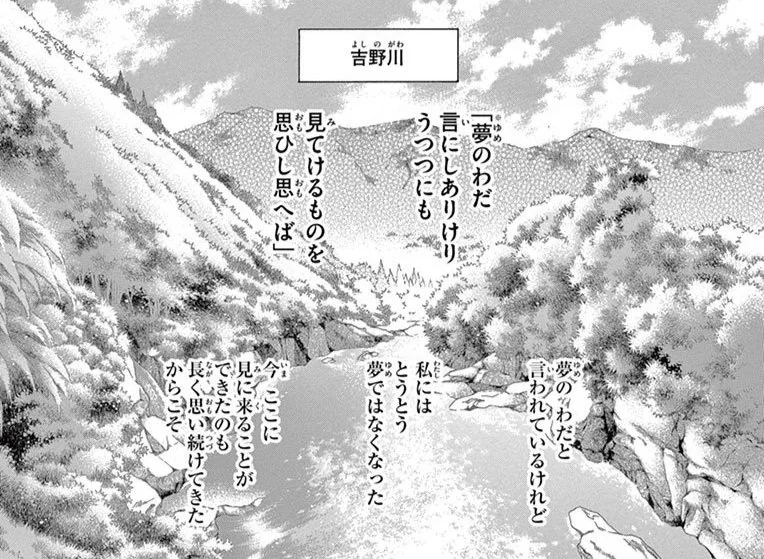

Panel from volume 3, page 79.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

At the beginning of Episode 13, Togu and her entourage reach Yoshino, and the chapter opens with her looking out upon a body of water where two rivers, the Yoshinogawa and Kisadanigawa, meet. She then appears to recite a poem, shown first in classical Japanese, and then followed by an explanatory modern Japanese version:

夢のわだ 言にしありけり うつつにも 見てけるものを 思ひし思へば

(夢のわだと言われているけれど 私にはとうとう夢ではなくなった 今ここに見にくることができたのも長く思い続けてきたからこそ)

This poem comes from the Man’yoshu, one of the most significant poetry anthologies in Japan, which was compiled by some time in the Nara period (710-794 CE). That means that we aren’t expected to imagine that Togu just came up with this by herself, but that she too is referring to well-known existing literature. It’s a very apt poem for her situation, as it is about the place she’s visiting! Yume no Wada (which translates roughly to “pool/ravine of dreams”) is a name for this location, and in the poem, the narrator shares the feeling of finally seeing it for themselves after having wanted to for a long time.

When I first tried translating this, I had to rely heavily on the modern Japanese version provided as well as other modern glosses and explanations available (like this one and this one). But I can now approach it a bit differently, as I’ve recently been in Japan studying classical Japanese (kobun) and visiting locations including Yume no Wada!

Learning how to read classical Japanese obviously helped me to understand poems like this one. I should point out that since “classical Japanese” refers mainly to the language as used in the Heian period, there are aspects of Nara period usage that are different from what I studied – this might be why there are expressions in the poem I can’t just conveniently find in my classical dictionary! Still, being able to analyse a poem like this and at least work out which parts require additional research makes the task much more realistic.

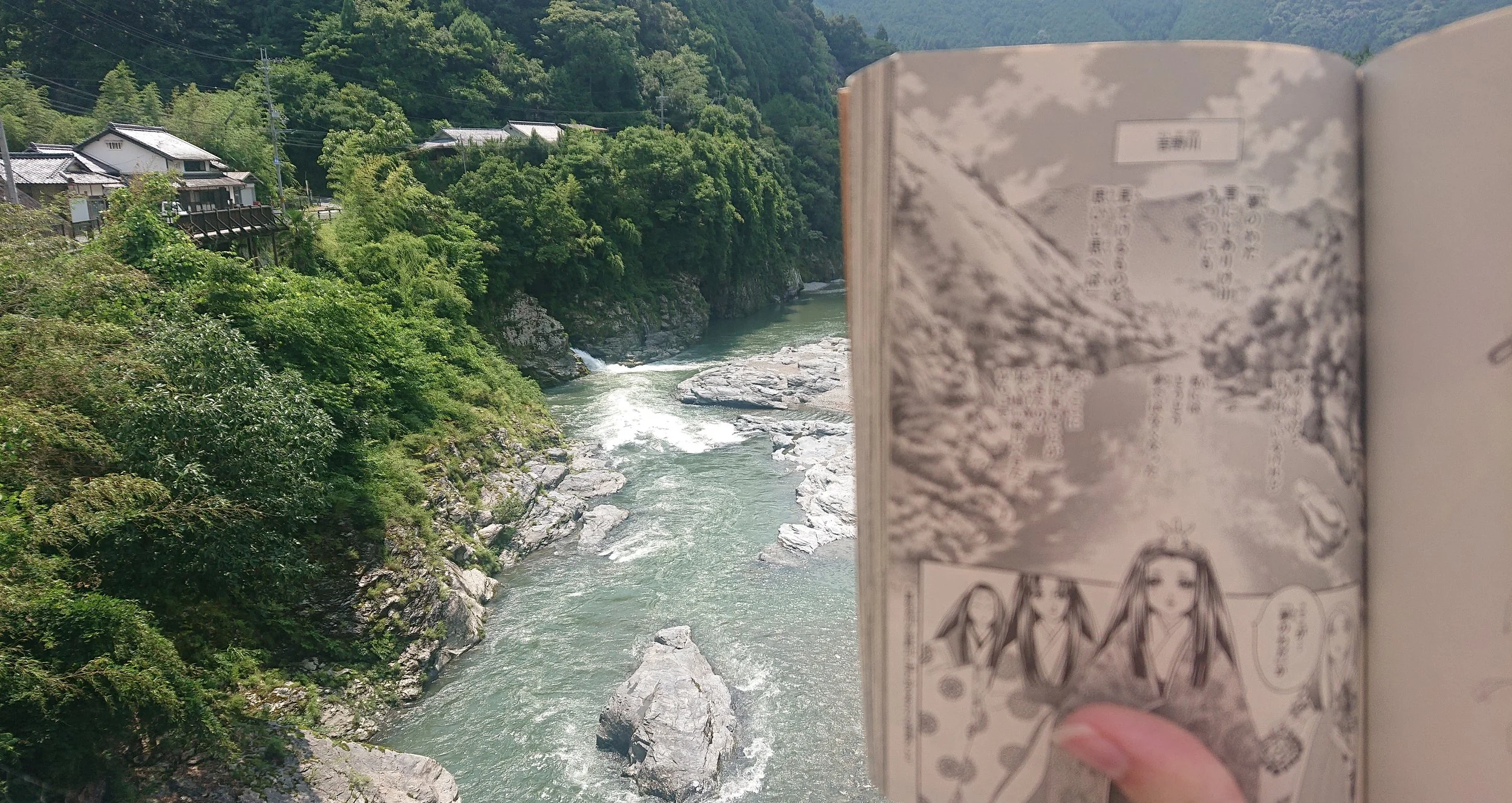

And going there in person was also helpful! At first, I had “wada” down as “cove”, because even with dictionary entries and the detailed image in the manga, it was hard for me to quite understand the nature of this bit of water. From seeing it for myself, I understand that the Kisadanigawa is much narrower than the Yoshinogawa, and that where the narrow part feeds into the wider river, it forms this slower-moving patch of water.

And so, armed with this knowledge, I feel better able to do justice to this interesting use of additional literary references! Here is my current translation:

“Yume no Wada” / is but a name. / Wide awake, / I have now seen it, / just as I long dreamt.

(They call it the Pool of Dreams, but it is not merely a dream to me any longer. I have finally come to see it for myself, all because I desired to for so long.)

I like to think that now that I know more and I’ve given it some deeper thought, I’ve come up with a decent translation. Something that was actually quite handy about rendering this in English is that “dream” can be used to mean “long for [something]”, letting me incorporate the poem’s contrast between dreams and reality in a slightly different way that meant I could keep the order of information the same as in the original poem. Meanwhile, having the lengthier modern version as an opportunity to go into more detail about the meaning allowed me to stick to something brief and abstract for the poem itself.

And of course, it wasn’t lost on me that making a pilgrimage to the spot where Togu cites the poem about finally seeing the “pool of dreams” in real life doubled up on the original reference. So to commemorate the dream-versus-reality within a dream-versus-reality, I also recited the poem and took a picture of the manga page next to its real-world counterpart!

Thoughts from Episode 13: An encounter with a tengu (?)

It’s been a while again! I’ve been on a trip, which is still ongoing, and it’s kept me a bit too busy to cope with weekly posts (especially yesterday, which was a VERY big day!). On the bright side, as I indicated last time, it is at least a trip that will give me plenty more to say at a later date. Look out for that in a few weeks’ time!

Anyway, we left Sara, Suiren and Nanten no Togu last time as they were approaching Yoshino. Yoshino was known even back then for cherry blossoms, but as our friends are going there in summer, Sara suggests the more seasonal activity of firefly catching. He brings Suiren and some attendants, but Sara and Suiren soon become separated from the group and encounter what appears to be a tengu.

It’s been a while again! I’ve been on a trip, which is still ongoing, and it’s kept me a bit too busy to cope with weekly posts (especially yesterday, which was a VERY big day!). On the bright side, as I indicated last time, it is at least a trip that will give me plenty more to say at a later date. Look out for that in a few weeks’ time!

Anyway, we left Sara, Suiren and Nanten no Togu last time as they were approaching Yoshino. Yoshino was known even back then for cherry blossoms, but as our friends are going there in summer, Sara suggests the more seasonal activity of firefly catching. He brings Suiren and some attendants, but Sara and Suiren soon become separated from the group and encounter what appears to be a tengu. Sara boldly tries to attack the “tengu” only to get knocked out and taken away, followed by Suiren. The “tengu” speaks to them in his villa when Sara wakes up, and immediately works out the siblings’ big secret.

The next day, Sara and Suiren are back with Togu, who has heard they had an adventure – when suddenly, the “tengu” appears! It turns out that he is none other than Yoshino no Miya, a reclusive member of the imperial family. He and Togu discuss the difficulties going on back in the capital, which she worries is the result of having a girl as the heir to the throne. Yoshino tries to console her and talks about destiny. He later sends Sara and Suiren on their way, makes some more mysterious comments and says he is sure they will be back.

Finally, Sara returns to Kakumitsu’s residence just as Tsuwabuki is leaving. Tsuwabuki makes an awkward excuse for being in the area and goes on his way, but Sara then goes to see Shi no Hime and smells something that reminds him of a certain work colleague…

Episode 13 is actually the first chapter that I translated! About this time last year, I did a translation pilot to test out my approach and the format of the translation, so I decided to select two consecutive chapters that were fairly representative, had plenty of variety and exhibited a lot of what makes Torikae baya interesting. That means I actually dealt with Episodes 13 and 14 quite a long time ago – but of course they could do with some updates considering everything I’ve been doing since.

Panel from volume 3, page 87.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

One of the great things about this chapter is that it introduces Yoshino no Miya! He has an equivalent in the original Torikaebaya monogatari, but like many of the characters in the manga, his role and characterisation are expanded here. He is a learned man who has studied various esoteric subjects in China, and was once an important figure at court until he left amid controversy and became an ascetic.

When Sara and Suiren first encounter him, both are immediately reminded of the tengu that is supposed to have cursed them – something I talked about in a much earlier blog post. They have this impression because, like the tengu gang from Episode 1, Yoshino is dressed in the clothes of a yamabushi. His divination skills – predicting years earlier that the Togu we know would become Togu, determining Sara and Suiren’s secret just by looking at their faces – also contribute to the sense that he is supernatural in some way.

I’ve mentioned previously that the idea of the tengu’s curse is greatly expanded in the manga from what was, in the original text, a brief explanation of what the siblings’ deal was and why it had been resolved. Basically, in Torikaebaya monogatari, it is revealed in a dream far into the story that a tengu cursed the father due to bad karma, causing the siblings’ situation, but the curse has now been alleviated.* But in the manga, the siblings believe they themselves are cursed and don’t know what to do about it.

*In the published version of Willig’s translation, this is attributed to the father becoming a devout Buddhist – maybe due to editing an ambiguous line in the first version – but a reviewer said it was actually the tengu that found religion. Incidentally, the original original wording genuinely does seem quite ambiguous.

Combined with associations between tengu, yamabushi and other monks, this could be a reason for Torikae baya’s Yoshino to be repeatedly identified with the tengu. Apart from this first appearance, he also later compares himself with a tengu, he is very knowledgeable about fate/destiny, and he treats his old difficulties at court as a dark past he has struggled to turn his back on.

Altogether, we end up with a fascinating character and an important layer of the tengu/curse motif in Torikae baya, which is, for me, one of the most interesting examples of the manga expanding on aspects of the original story.

Thoughts from Episode 12: The seasons in Torikae baya

I took a break from posting last week because I just had too much happening – more on that in a future post! – but I’m back today to talk about Episode 12 and to say a bit more about a topic that I’ve touched on previously.

In this chapter, Tsuwabuki and Shi no Hime’s affair continues. Tsuwabuki finds out the sad story about Shi no Hime’s scar, but to her surprise, it doesn’t faze him. She wonders whether his passion for her is a stronger love than she has with Sara, whom she now suspects might love somebody else instead, and wishes she and Sara could connect in the same way.

I took a break from posting last week because I just had too much happening – more on that in a future post! – but I’m back today to talk about Episode 12 and to say a bit more about a topic that I’ve touched on previously.

In this chapter, Tsuwabuki and Shi no Hime’s affair continues. Tsuwabuki finds out the sad story about Shi no Hime’s scar, but to her surprise, it doesn’t faze him. She wonders whether his passion for her is a stronger love than she has with Sara, whom she now suspects might love somebody else instead, and wishes she and Sara could connect in the same way.

One day, as she feeds the birds Sara rescued in Episode 10, the long-suffering Saemon points out that Shi no Hime hasn’t had a period in three months. Cut to Kakumitsu’s excitement at her pregnancy! This comes as quite a shock to Sara, who had no involvement and who wonders who the father could possibly be. The news quickly spreads, and eventually Sara breaks down in tears in front of his father Marumitsu. Sara tells Marumitsu and his mother Nishi that he might either break up with Shi no Hime or tell her the truth and try to continue as before, but Nishi is opposed.

Meanwhile, it turns out that Togu is going on a trip to Yoshino and that Sara will be part of the entourage. On the way there, Togu comments on Sara and Suiren’s physical similarity and tells them about her remarkable relative, Yoshino no Miya, a man she believes can predict the future.

A few weeks ago, I tried to go over Torikae baya’s timeline, and today I want to say a bit about the seasons and their significance in the narrative. In that previous post, I mentioned that details like seasonal events and flowers give some indication of the time of year and the passage of time more generally. This week’s chapter in particular makes thematic use of this.

Not much time has passed over the last few chapters, but notably it’s been spring throughout, as indicated mainly by the presence of cherry blossoms and wisteria. Episode 10 drew attention to the season in its title, A Spring Night’s Moon (春の夜の月). Because of the original phrasing, I’m inclined to think that this title is an intentional reference to A Midsummer Night’s Dream. This is just one example of something we’ll see more of: deliberately unseasonal references.

Episode 12 also refers to the season in its title, with The End of Spring (春の終わり). It’s a literal description of where we’ve got to in this busy year, but it’s also metaphorically apt. Sara and Shi no Hime’s marriage began in winter and has figuratively blossomed during the spring, but Shi no Hime’s pregnancy signals the end of that.

During this chapter, Shi no Hime muses that Sara’s kindness towards her is like “dappled sunlight in spring” – matching the season where she has come to know him. This is in contrast with Tsuwabuki’s intense love, which she describes as “like an autumn storm is relentlessly blowing me off my feet”, complete with autumnal visual imagery. The “autumn storm” in this case is 野分, the name for a typhoon in the early autumn (and a chapter in The Tale of Genji). So while she is comforted by the seasonally appropriate affection of Sara, Tsuwabuki’s unseasonal passion comes as a shock and a thrill.

There will be more moments like this later too! We’ve had instances of late-blooming cherry blossoms already, and there is another major one in a future chapter, which itself is called 野分. But I’m afraid you’ll have to wait until later to hear more about that!

Thoughts from Episode 11: “Words mean nothing”

Back to a more typical post this week, looking at Episode 11 and then getting into a bit of poetry!

This chapter begins right as the last one left off, with Tsuwabuki approaching Shi no Hime. It’s not long before he has his way with her, learning in the process that her husband Sara hasn’t – much to his surprise and confusion. As he leaves in the morning, eager to visit again, Shi no Hime’s attendant Saemon takes pity on Tsuwabuki and continues to exchange letters with him.

Back to a more typical post this week, looking at Episode 11 and then getting into a bit of poetry!

This chapter begins right as the last one left off, with Tsuwabuki approaching Shi no Hime. It’s not long before he has his way with her, learning in the process that her husband Sara hasn’t – much to his surprise and confusion. As he leaves in the morning, eager to visit again, Shi no Hime’s attendant Saemon takes pity on Tsuwabuki and continues to exchange letters with him.

After all that, Shi no Hime stays in bed and is too ashamed to speak to Sara when he gets home. Though he can’t figure out what the problem is, Sara takes time off from work to look after her. When he returns to work, he is told that Tsuwabuki has also been missing, but when he tries to pay him a visit, Tsuwabuki won’t see him. This is because he is also ashamed, but not so ashamed that he’ll give up on Shi no Hime. Soon afterwards, Shi no Hime finds out that Tsuwabuki has been writing letters, and decides to invite him round to break up with him, but… let’s just say that doesn’t work…

If you’re wondering what today’s title is all about, “Words mean nothing” is the smooth line Tsuwabuki says to Shi no Hime at the end of this chapter (originally 言葉なぞ無意味). Of course, it does make sense in context, but there’s something quite ironic about this line considering the prominent use of poetry in Tsuwabuki’s attempts to woo Shi no Hime. And this is an aspect where, in Torikae baya, Saito directly incorporates some of the original text of Torikaebaya monogatari!

First, it’s worth mentioning that poetry was a big deal for the people of the Heian court. For someone to matter in that world, they were expected to be both knowledgeable and skilled when it came to poetry. There were all sorts of situations where people of the court would write and recite poetry, and we get a little sense of that throughout the early chapters of Torikae baya. An early sign of Sara’s affinity for boys’ activities is when he offers to show a visitor, Captain Emon, a poem that he has written. As times goes by, we also get a sense of how important poetry is for romance: Tsuwabuki’s friend Minamoto no Tadasuke shares a sad story about how he sent a poem to a girl he liked, only for her to send it back with corrections; Tsuwabuki pesters Sara to let him send poems to Suiren; and Sara kicks off marriage proceedings with Shi no Hime by writing her a poem.

So far in Torikae baya, five poems have been quoted directly from the original story, accompanied each time by a modern Japanese translation/explanation (remember that Torikaebaya monogatari is from the late Heian period, probably the 1100s). I won’t go into much detail on all of them, but I’ll at least share them all here! The first is in Episode 4, when Sara attempts to convince Tsuwabuki to give up on getting to know his sister. He says (original* first, Saito’s modern Japanese version second):

たぐいなき 憂き身と思い 知るからに さやは涙の 浮きて流るる

(世に類のない生き辛い我が身と思い知ってるから そんな私でさえそんなふうに涙を流したりしないのに)

In this scene, Sara tries to reject Tsuwabuki’s friendship entirely. Ruled by passion as always, Tsuwabuki begins to cry, and Sara’s poem laments that though he himself has so much to worry about, he can’t bring himself to cry as easily as Tsuwabuki. This poem highlights the differences in personality between Sara and Tsuwabuki – and indeed, between their counterparts in Torikaebaya monogatari. Including it in the manga makes the moment stand out and really feel like an instance where Sara is unable to contain his melancholy.

The next quoted poem comes from Sara again, when he writes to Shi no Hime in Episode 6:

これやさは 入りて繁きは 道ならむ 山口しるく 惑はるるかな

(これが人のいう恋路の山でしょうか? 早くもほんの入り口で心乱れている私です)

Next, a pair of poems are taken from Torikaebaya monogatari. This is in the Episode 10 scene where Tsuwabuki, being weird about Sara’s coat, overhears Shi no Hime playing the koto and reciting poetry. Shi no Hime says:

春の夜も 見る我からの 月なれば 心づくしの 影となりけり

(明るい春の夜も見る者それぞれの感じる月だから 暗い心の私には月も暗いように感じられる)

What I’ve been doing with these poems so far is taking advantage of there being two of them, by writing a first translation that is shorter and more abstract, and a second one that elaborates a bit more on the poem’s implications. Either way, I’ve been relying quite heavily on the modern Japanese versions (and other modern Japanese versions besides the manga) because of my limited experience with classical Japanese, but that’s all changing as we speak! With funding from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation, I’m on a summer course for classical Japanese right now, so I’m hoping to come back to these poems and do a much better job later.

But for now, you probably want to know about Shi no Hime’s poem, so I will give you what I’ve written in the current draft:

On a spring's night, the moon is still that of its viewer. My heart's disquiet is reflected therein.

(Even on a bright night in spring, the moon feels different for each person. So when I feel gloomy inside, the moon is gloomy too.)

Now, as I said, this is the first in a pair of poems, both drawn from the original Torikaebaya monogatari. The second in the pair comes from Tsuwabuki. He has heard Shi no Hime’s forlorn poem and concludes both that she understands his feelings and that she must be unhappy with her marriage. Because he always had a thing for Shi no Hime, he decides that this is his big chance, so he responds:

忘られぬ 心や月に 通ふらむ 心づくしの 影と見けるは

(あなたを忘れられない私の心が月に通じたのでしょうか あなたが月を暗いように感じたのは)

And here is what I have at the moment:

My unforgetting heart must have touched the moon, if you see a reflection of your heart's disquiet.

(I could never forget you. Perhaps those feelings of mine affected the moon, if you feel that it is gloomy.)

I’ll leave it for you to decide whether these translations are up to scratch, but hopefully you can at least see how they communicate with one another! Not every poem from the original makes its way into the manga, so again, the inclusion of these poems does a lot to help the scene stand out. It feels like a big moment, and one where perhaps it would be a disservice to the story to try and convey it through means other than poetry.

And finally, for the sake of completion, here is the poem that comes up in this week’s chapter. Tsuwabuki, who now feels like Shi no Hime was always the one for him, recites this poem right before he leaves her in the morning:

我がために えに深ければ 三瀬川 のちの逢瀬も 誰かたづねむ

(女は初めての男に背負われて渡ると言われる三途の川 あなたを背負うのは私ですよ それほどあなたと私の縁は深いのです だからどうやって逢瀬を重ねたらよいか教えてください)

You’ll likely notice that the modern Japanese version is significantly longer this time, mainly because it requires an explanation of stories about the Sanzu River. But at this point, I’ve already gone on more than long enough, so I’ll leave it there – but you can expect to hear more about poetry very soon!

*There is a bit of variation in the orthography, so some of these might have been made slightly easier for today’s readers, but the words themselves are as they were in the original text.

Digression: Keeping track of time in Torikae baya

Something I’ve been doing as I’ve worked through the translation is noting indications of the passage of time in Torikae baya. The story takes place over several years, and while some of the jumps forward are made quite clear, there are other subtler indications too, and I want to make sure there’s nothing I’m missing! I’ll say a bit today about how much time has passed in the series so far and what kind of details I’ve looked at, but if you just want the basics, you can also take a look at the new timeline page I put together!

Something I’ve been doing as I’ve worked through the translation is noting indications of the passage of time in Torikae baya. The story takes place over several years, and while some of the jumps forward are made quite clear, there are other subtler indications too, and I want to make sure there’s nothing I’m missing! I’ll say a bit today about how much time has passed in the series so far and what kind of details I’ve looked at, but if you just want the basics, you can also take a look at the new timeline page I put together!

First, when does this take place? The original Torikaebaya monogatari was probably written in the late Heian or early Kamakura period, and the setting for the story is definitely some point in the Heian period. There have been a couple of times where I got into rabbit holes trying to work out exactly when the manga could be set based on things like dates of historical eclipses. I even concluded at one point that it wasn’t chronologically possible, because there are references to Yoshino no Miya having been on a mission to Tang China, but it’s also made clear that The Tale of Genji already exists.

The end result of all this is that I don’t really know! Maybe the Tang reference is just outdated terminology for the time period, or maybe the timing really isn’t intended to be very specific.

But at least on a closer level, we can work out some details about the timeline! Early on, it’s made quite clear how much time passes: the story starts with Sara and Suiren being born, the major kidnapping incident takes place six years later, and the discussions about Fujiwara no Marumitsu’s son taking a job at court begin when the siblings are almost 14 – time for becoming an adult, as far as everyone in this setting is concerned. The next clear indication of characters’ ages comes in Episode 6, when we hear that Shi no Hime – 19 years old – is three years Sara’s senior. Otherwise, we generally have to rely on other clues.

I want to come back to the point about coming of age though. It’s worth noting that Sara and Suiren are pretty young, at least by the standards a lot of us would expect. This also applies to other characters. Tsuwabuki mentions once that he is 18, and soon afterwards he says that Sara is still 16 at that point, so they’re just two years apart. We don’t know Nanten no Togu’s age, but she’s noted as seeming like a child despite her astuteness, so it’s probably fair to assume she isn’t too far away from Sara and Suiren’s age.

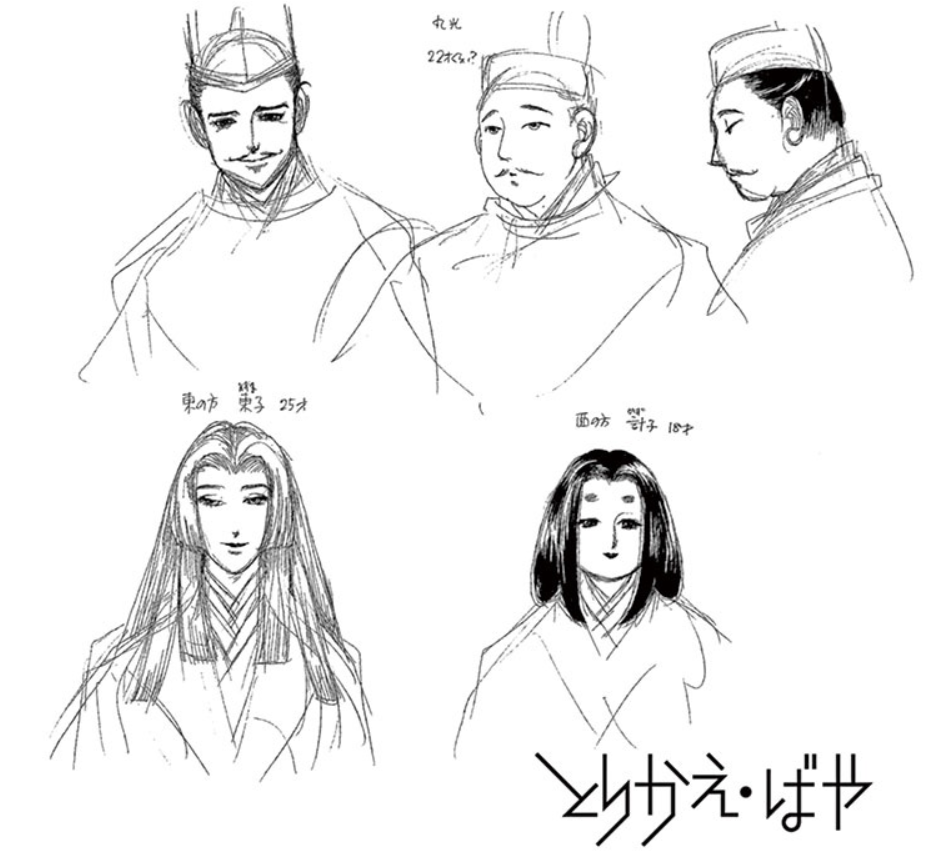

Production sketches of characters from volume 1, page 150.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

There are no in-text references to the age of Sara and Suiren’s parents, but there are some sketches included between chapters in Volume 1 that can help. There’s a sketch of Marumitsu, supposedly around 22 years old, and I think it’s fair to assume that’s as of when the siblings are born. There are also drawings of his wives, with Higashi no Ue (Suiren’s mother) at 25 years old and Nishi no Ue (Sara’s mother) at 18. This aligns quite well with the ages at which Sara and Suiren are entering adult life: if they can start working at 14 and get married at 16, it’s not so bizarre that they’d be having children somewhere around 20.

And as for other signs of the passage of time, we can look at details like seasonal events. The komahiki that takes place in Episode 2 is supposed to have been an August event, so it must be within the first few months of Sara entering the work force. The fact that the changing of the Emperors is specified to take place at New Year also helps set up the chronology of some of what follows.

After that, another thing I found myself looking at obsessively was flowers. Around the time of Sara’s marriage to Shi no Hime and Suiren starting her job as naishi no kami, we know that not much time has passed since New Year, because we see snow and because there’s a plum blossom party at the palace with the appearance of a notably unseasonable butterfly. In the next couple of chapters, there are frequent mentions of the cherry blossoms – showing that spring has come – and even more specific points like how far into the season it is, and the appearance of wisteria which typically comes just after.

I won’t write out everything that I’ve considered with respect to the timeline, but I promise there’s a lot! Again, please do check out the timeline page if you want to get a quick idea of what happens when – and I’ll be keeping it updated too!

Thoughts from Episode 10: Tsuwabuki, no!

A little bit of time has passed since the previous chapter, and now we see that Sara and Shi no Hime are getting along better: Sara brings her a nest of orphaned chicks to raise, they watch the moon together, and Shi no Hime calls Sara “se no kimi” (背の君), which Saito helpfully notes as a term of endearment for one’s husband. At night, though, Sara worries that he isn’t doing enough, while Shi no Hime worries that he might not really love her.

A little bit of time has passed since the previous chapter, and now we see that Sara and Shi no Hime are getting along better: Sara brings her a nest of orphaned chicks to raise, they watch the moon together, and Shi no Hime calls Sara “se no kimi” (背の君), which Saito helpfully notes as a term of endearment for one’s husband. At night, though, Sara worries that he isn’t doing enough, while Shi no Hime worries that he might not really love her.

Elsewhere, Tsuwabuki tests his new theory that he might be into men, by hugging his work buddies and seeing what happens. Just as he’s driving them nuts with his behaviour, the Emperor’s brother-in-law Shikibu-kyo no Miya appears and offers to teach Tsuwabuki about the joys of loving men, causing him to run off in a panic.

One evening, when Umetsubo is visiting her father Kakumitsu (remember that Shi no Hime is another of his daughters), Tsuwabuki suddenly appears and wants to see Sara. While Sara goes to deal with him, Umetsubo insinuates that Sara might not treat Shi no Hime “like a husband should”, eliciting a VERY defensive response. Sara and Tsuwabuki have a rowdy drinking session together, and when Tsuwabuki wakes up after passing out, Sara has already left for night watch duty. Tsuwabuki pathetically sniffs Sara’s coat until he hears someone playing the koto – Shi no Hime, the woman he coveted for so long! After hearing her recite an oddly sad poem for a happy newlywed, he decides to go and introduce himself… the only way he knows how.

Title page of Episode 10 from volume 2, page 149.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

This is the final chapter of the second volume, giving us a cliffhanger just as things really start going wrong. Tsuwabuki has recognised that he has feelings for Sara, but still hasn’t quite given up on trying to explain them away, with worse and worse results.

The thing I want to take a closer look at today is the chapter’s title page. I mentioned in an earlier post that the Episode 3 title page has some interesting details, portraying the then-Togu dressed like a Buddhist deity. There are many other wonderful title pages, showing off the major characters in a variety of flashy and often meaningful outfits. They’re often good examples of how Saito embeds symbolic details in the artwork, as I discussed a couple of weeks ago.

The title page this time shows Tsuwabuki, looking sad and thoughtful as he holds a coat (or an outer robe, but there aren’t always great equivalent terms for all the items of clothing they wear) close to himself. There are some decorative wisteria flowers in the background, and the coat he’s holding has a wisteria motif too. The image of Tsuwabuki holding the coat evokes the scene later in the chapter when he finds that Sara has left his coat as a blanket for him, while the flowers give us some sense of when this is taking place.

At first, I thought it was Sara’s coat in this image, but then I realised the pattern was different. I was happy enough at that point to say that the wisteria pattern just matched the flowers in the background, until I went through the chapter once again. In the scene when Tsuwabuki awkwardly hugs his friends, several men are taking wisteria branches to put in their caps, and Shikibu-kyo no Miya gives one to Tsuwabuki, lamenting that he no longer decorates himself with his trademark tsuwabuki flowers. And on top of that – when Shikibu-kyo no Miya appears, he is wearing the coat from the title page.

This adds more complexity to the coat situation, as if it weren’t bad enough already (Tsuwabuki even puts Sara’s coat on, so he’s trying it on with Shi no Hime in her husband’s clothes*). Now, the title page isn’t just a nice brooding picture of Tsuwabuki with a reference to the scene with Sara’s coat. By replacing the garment with Shikibu-kyo no Miya’s coat, it ties that scene to the worries Tsuwabuki has elsewhere in this chapter about his own sexual/romantic preferences.

And besides the significance of this particular image in this particular chapter, it’s good just to keep in mind (again) that for the translation, the visuals matter as well as the text!

*his other sins in this chapter include watching Shi no Hime through some blinds – just like he did with Suiren – and then introducing himself using the exact same words (“I am the Chancellor Colonel” – 宰相の中将にございます) as he did with Suiren…………

Thoughts from Episode 9: fellas,

Until now, there have been more than a few moments to make readers wonder who exactly Tsuwabuki is infatuated with, and in this chapter, the penny finally drops for him too.

Until now, there have been more than a few moments to make readers wonder who exactly Tsuwabuki is infatuated with, and in this chapter, the penny finally drops for him too. Following on from last time, Suiren has realised somebody is watching her from behind the blinds. As Tsuwabuki tries to woo her, she stalls for time by making him explain what he means by “love”. Suiren then wonders why his description aligns so well with her own feelings towards Togu – while Tsuwabuki wonders why he isn’t more excited to be meeting his supposed “ideal woman”. He gets impatient with Suiren and himself and tries to rush in (as is his wont) but Suiren fights back and he runs off with his tail between his legs.

Later, the Emperor sees the plum blossoms in Umetsubo’s quarters and immediately throws a party! Sara learns that Tsuwabuki has been moping, Umetsubo briefly stirs the pot, and Sara then goes to speak to Tsuwabuki while everyone is chasing after a butterfly. After a moment of panic when he finds out that Tsuwabuki tried it on with Suiren, Sara attempts to reassure his colleague that he’s still cool and manly even after being rejected. Tsuwabuki then lets slip that he finds Sara more attractive that Suiren (!) and when the butterfly lands on Sara’s cap shortly afterwards, the young guys’ hands touch (!!) and Tsuwabuki blushes (!!!). In the end, Tsuwabuki is left questioning whether his feelings are really for Suiren or for Sara.

Something that Saito does a lot in Torikae baya is setting up parallels between different characters or situations: for example, Episode 7 compares Sara’s first meeting with Shi no Hime and Suiren’s first meeting with Togu, and ends with both siblings nervously thinking about “sleeping in the same bed” (同じ御帳台に寝る). And then in the current chapter, Suiren wonders “Am I… in love with Togu-sama!?” (東宮さまに恋していたのか⁉私は) while Tsuwabuki asks himself “Am I not in love… with this woman?” (恋してない―のか?自分は).

Along those lines, I’ll talk a little bit today about a couple of techniques where one thing is mapped onto another – one of these uses furigana and the other is in the art itself.

First, when Suiren realises that the mystery man behind the blinds is Tsuwabuki, she has a brief flashback to when Sara was telling her about him, and then this happens:

In the present, TSUWABUKI can still be seen through the blinds, one hand raised.SUIREN [thinking] The man who desires me…

SUIREN pictures the TENGU caressing a scared young SUIREN’s face.

SUIREN [thinking] A man.

Looking across the room, SUIREN shouts out in fear.

SUIREN [thinking] The tengu!!

Suiren’s second line here is originally 男, with おとこ written to the side as furigana – straightforward so far. The third line is 天狗…!! but rather than being written with the furigana てんぐ, this is also glossed as おとこ. Techniques like this are used pretty often in manga, allowing the writer to do things like providing quick translations/explanations of unusual or strangely written words, or suggesting multiple meanings at once, like Saito does here. Mapping the sound of “otoko” onto the kanji for “tengu” lets her convey both ideas at the same time.

In this case, all we need is a one-word line and an image of the tengu from Episode 1 to understand that Suiren’s worries about men are closely linked to her and Sara’s childhood experience of being kidnapped. For her, any man could potentially be a tengu, and therefore a serious threat.

Panel from volume 2, page 142.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

The other example of mapping one thing onto another comes later in the chapter. Tsuwabuki has just admitted that he thinks his work buddy is prettier than his work buddy’s famously beautiful sister and then tellingly asked himself “Was that a weird thing to say?” (おれ今 変なこと言わなかったか?). He says he used to imagine Suiren’s appearance when looking at Sara, and then looks at Sara while picturing Suiren’s face alongside.

On the one hand, this highlights how similar Sara and Suiren are in appearance. On the other, it gives us a sense of what Tsuwabuki has been seeing all along, and how, now that he’s seen Suiren too, this has taken on new meaning for him. The moment where we see Sara and Suiren as if they were one person acts as a turning point in this plotline. It’s right after this that Tsuwabuki begins to question the true nature of his own feelings.

Maybe all those times he told his colleague “your sister must be smoking hot if she looks just like you”, it wasn’t reeeeeally about the sister…

Thoughts from Episode 8: Exit, pursued by a tengu

Episode 8 picks up right where we left off, with Sara and Shi no Hime in bed together... just lying there awkwardly. Sara recalls a drinking party where Tsuwabuki taught him about the birds and the bees, but sees no way to put that into practice, so instead, he holds Shi no Hime’s hand the whole night.

Episode 8 picks up right where we left off, with Sara and Shi no Hime in bed together... just lying there awkwardly. Sara recalls a drinking party where Tsuwabuki taught him about the birds and the bees, but sees no way to put that into practice, so instead, he holds Shi no Hime’s hand the whole night. In the morning, we see some signs that the newlyweds might actually get along.

In the Nashitsubo pavilion, Togu reads until she falls asleep, and Suiren ends up having to also lie awkwardly next to her. When Togu wakes up, Suiren leaves, deeply embarrassed. Later on, Suiren and another attendant are told that Togu won’t be needed for the day’s activities, even though she’s been working hard to prepare. Suiren overhears some sneering officials mocking Togu, but chooses not to reveal the whole truth to her. As it turns out, though, Togu is well aware of the men’s attitudes and has quite complex thoughts about her position in the palace. She appreciates that Suiren avoided making a scene, inspiring Suiren to do all she can to help her.

Finally, Tsuwabuki is in a bad mood. We hear from his buddies that he’s been struggling ever since his best friend married the woman he’d been lusting after. Suddenly, wanting to deal with his confused feelings, Tsuwabuki goes to pay Suiren an uninvited visit – and that’s where the chapter ends.

Today, I’d like to talk a bit about one of the practical aspects of my translation. For a few reasons, I’m formatting it like a script: in the margin is an indication of the speaker, and that’s followed by their lines of dialogue, one speech balloon at a time. I fit the various other text in too, like titles, narration and sound (or not sound) effects.

But that’s not necessarily enough to give the reader a sense of which translated line corresponds to which bit of text. And it’s definitely not enough for a reader who can’t constantly cross-reference with the manga page. My solution for this is image descriptions! In between the dialogue and other text are brief descriptions of what’s going on visually, a bit like stage directions, to provide context.

This is something I’ve been doing since the very start, but I wanted to bring it up now because there are a couple of good examples. I’ll share a humorous one, from when Sara remembers hanging out with Tsuwabuki and his friends:

Panels from volume 2, page 82.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

TSUWABUKI smiles confidently.

TSUWABUKI It's all about having your way with her.

SARA remains confused, while TSUWABUKI smugly continues.

SARA What do you mean, "having my way"?

TSUWABUKI Well, you see...

We see TSUWABUKI provide SARA with an unspecified explanation. They are surrounded by pairs of anthropomorphic rabbit silhouettes in various suggestive positions and upper- and lower-case “A”s. SARA looks scandalised; the tails on his cap are sticking up like rabbit ears, and arrows poke out from his back in random directions.

This was a fun bit to try and describe! I think it’s also a good example of why the descriptions are useful to have. Without some sense of what’s going on visually, the scene would be A) confusing and B) not funny.

At the end of the chapter, there’s also a more serious example, where Tsuwabuki’s visit to Suiren is shown in a two-page spread with no dialogue. That means that the description is the only indication that anything is even happening on those pages. And in other chapters, there have been details in panels that I might have overlooked if I hadn’t been thinking about how to describe them – like flowers associated with particular characters, for example.

Manga is a visual medium. Just like the narration in a novel, the visuals in manga are a fundamental part of how it conveys meaning. Images don’t really need to be translated, so dialogue and other text is always going to be the focus in a translation (I’ve never had to write image descriptions for a manga translation before!) but in one way or another, the visuals do have an impact on the translation. And these odd little stage directions are one way I’ve chosen to reflect that!