Blogging about my Torikae baya manga translation project.

Thoughts from Episode 29: The world beyond the capital, the cast beyond Sara and Suiren

A more typical post today, going over Episode 29 and having a little look at how the cast of the original story expands in Torikae baya.

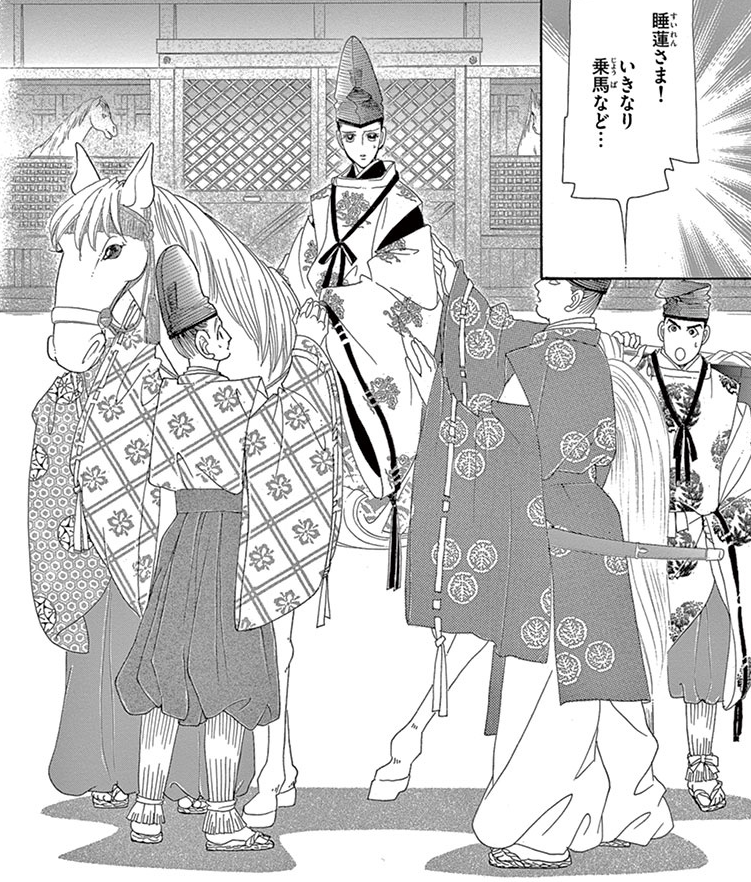

Suiren, now looking just like Sara used to, is ready to go looking for her brother… except she doesn’t know a lot about going about as a man, riding horses, etc. But with some help from some servants who knew her as a child, she hides away in a palanquin and searches around Heian-kyo. There’s no sign of Sara at Aguri’s home, nor at Saemon’s, but at the latter she spots Tsuwabuki and realises he was Shi no Hime’s secret lover.

A more typical post today, going over Episode 29 and having a little look at how the cast of the original story expands in Torikae baya.

Suiren, now looking just like Sara used to, is ready to go looking for her brother… except she doesn’t know a lot about going about as a man, riding horses, etc. But with some help from some servants who knew her as a child, she hides away in a palanquin and searches around Heian-kyo. There’s no sign of Sara at Aguri’s home, nor at Saemon’s, but at the latter she spots Tsuwabuki and realises he was Shi no Hime’s secret lover.

Meanwhile, Sara is in Uji, encouraging Tsuwabuki to check on the poorly Shi no Hime and generally getting tired of his nonsense. Suiren and her entourage also come to Uji and ask around for a man who looks just like Suiren. Little do they know that Sara is having a stroll nearby with Torako and Toramitsu! Sara gets worked up after seeing a performance involving a tengu, then collapses in pain – but not before making eye contact with Suiren by pure chance. Of course, neither understands what they’ve just seen, and so Suiren departs, believing that Sara is nowhere to be found.

Plenty happens in this chapter, and we get nods to ongoing themes – Suiren’s discomfort in trying to take on a masculine role, Tsuwabuki’s naïve dreams of a happy family with as many wives as he likes, the seemingly mystical connection between Sara and Suiren, even a tengu! – with some striking visuals along the way. I’ll have more to say about these things later, but today, I want to return to an old topic and talk about the cast of Torikae baya.

The source material doesn’t introduce a lot of specific characters, and even fewer by a consistent name or identifier. Most of them appear in the manga too, in some cases being given nicknames in addition to their changing ranks. The most obvious examples are Sarasoju and Suiren, whom we might have some difficulty recognising at this point in the story, with Sara staying at Tsuwabuki’s villa dressing in women’s clothes and Suiren searching for him while dressed in men’s clothes.

But of course, manga is not the same as a (mostly) prose narrative from the Heian period. In totally verbal storytelling, only the plot-significant characters really need to be mentioned, and the reader’s imagination can fill in the blanks with as many background figures as one might expect in the busy palace. But unless you go all closeups all the time, a manga adaptation needs to show the Heian court in action, so a handful of characters just isn’t enough!

Sara imagines Akimasa and Tadasuke’s reaction.

Panel from volume 4, page 7. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

That means some characters from the original story have new, expanded roles, such as Togu, Umetsubo, and to a lesser extent, people like Aguri and Saemon. In addition to those, though, are many, many more. Some character designs reappear, suggesting they are meant to be the same person showing up again and again. I asked Saito about whether she had names or titles in mind for any of the unidentified background characters, and she indicated that she avoided doing that as she didn’t feel confident enough about the time period to get it right when going beyond the source material. But she does name new characters sometimes. The danger of getting details wrong is often mitigated by having the identified characters be true one-offs whom we never hear from again, but there are quite a few who are recurring characters.

The most prominent of these so far are probably Tachibana no Akimasa and Minamoto no Tadasuke, the Lenny and Carl of Sara and Tsuwabuki’s work lives. Their purpose in the story is to demonstrate that Sara is well-liked at court and has friends who aren’t Tsuwabuki: they show up at social events, and theirs are the faces Sara pictures in Episode 16 when he worries about people’s reactions if they were to learn of his secret. They appear several times, and Akimasa is also integrated a bit more into the goings-on of the Heian court, turning out to have a job as a high steward (式部 の 大輔 – shikibu no taifu) under Shikibu-kyo no Miya.

A few named minor characters appear in Episode 29. Torako and Toramitsu arguably appear in the original story – there are brief mentions of children of the siblings’ wetnurses – but otherwise they’re pretty much new characters. Torako in particular plays a fairly substantial role, continuing to serve Sara even long past this point in the story.

Pictured: Suiren (dressed as Sara), Gyuomaru, Jiroemon, Hayabusamaru, another guy.

Panels from volume 6, page 118. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

We’re introduced to Suiren’s male servants too. One is apparently Sara’s former stable hand, and he introduces himself as Gyuomaru, while another is called Jiroemon. Suiren’s mother picked out these two and three other unnamed guys specifically because they knew Suiren as a child, and it’s possible these also correspond to the vague “wetnurse’s children” from Torikaebaya monogatari, but they’re effectively new characters. And besides them, this chapter mentions other people in passing, like Kakumitsu’s wife/Shi no Hime’s mother – who later makes a brief appearance – and Jiroemon’s aunt, a maid named Hiiragi. We even learn that Sara’s old horse is called Hayabusamaru!

While not every chapter has quite so many recurring or named characters, it’s fair to say that Saito does expand on the core cast more than she thought she dared to. And I think it’s for the best! It just wouldn’t be very interesting if an adaptation in a visual medium like manga didn’t show a bit more life in Heian-kyo, so adding these supporting characters is arguably just as important as showing all the historical architecture and beautiful clothes.

I’ve been meaning to put together a chart of the characters and their relationships at some point, a bit like the ones that already exist in the manga volumes. Of course, including everyone would make it much more complicated than the existing charts, and that’s what’s stopped me so far… but I still want to do it one of these days!

Digression: 2025 wrap-up party

I’ve had a bit too much happening to stick to a regular posting schedule in the last couple of weeks, but I want to fit one last one in before the year is up!

After spending quite a lot of time in the first few years of the PhD making preparations and trying to work things out, I finally managed to focus on the main practical work of the project this year, and I’m happy to have made a lot of progress. So today, I want to go over what’s happened in 2025 and what comes next!

I’ve had a bit too much happening to stick to a regular posting schedule in the last couple of weeks, but I want to fit one last one in before the year is up!

After spending quite a lot of time in the first few years of the PhD making preparations and trying to work things out, I finally managed to focus on the main practical work of the project this year, and I’m happy to have made a lot of progress. So today, I want to go over what’s happened in 2025 and what comes next!

The biggest thing of course was working on translating Torikae baya, one chapter at a time. At the outset of the project, I had visions of a scanlation of all 13 volumes, but this was reined in early on for a few reasons. Because of the impracticality of basing everything around images and the greater potential for copyright issues, I decided to format the translation a bit like a screenplay, in a way that should make it readable both to people who can view the original manga pages alongside and people who can’t. A nice upside of this, which I discussed briefly here, is that the need to describe the images helps me notice details I might’ve missed otherwise and ensures I pay appropriate attention to the visual side of the medium.

Meanwhile, earlier experiments with the style of the translation made it clear that 13 volumesworth (65 chapters) was never going to be even close to fitting into the accepted limits for the thesis, and it would mean spending a lot of time translating large portions that would be unlikely to make the final cut. So the plan was to translate volumes 1 to 7, then skip to 13.

These aren’t just random numbers! I couldn’t pick the exact chapters to include in the thesis proper without actually doing the work of translating them and learning through the process what material would be most relevant. However, I was confident early on that I would want to say a lot about this series as an adaptation of Torikaebaya monogatari, so I chose to focus on translating the portions that follow the original plot most closely – a lot of the manga’s totally new material comes between Sara and Suiren’s return to the capital and the ending. This will still be too much to fit within the word count restrictions for the thesis, so I’ll need to whittle down the 40 translated chapters to somewhere between 15 and 20 that are especially significant, while the rest will probably end up in an appendix.

Another big event this year was my trip to Kyoto in the summer, with funding from the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation, the Japan Foundation Endowment Committee and Edinburgh University’s School of Literatures, Languages and Cultures. I studied classical Japanese language, visited locations from Torikae baya along with places like the Kyoto International Manga Museum, and I even got to meet Saito Chiho and ask her questions about the process of writing Torikae baya (I can still hardly believe that really happened!). Altogether, the trip gave me important ideas and insights for the project, and changed how I think about the Japanese language. It was a lot of fun too!

Around the same time as that trip, one exciting development was that I moved from part-time to full-time study. Part of the slowness up to that point came about from being limited in how much time I could devote to working on the project, but fortunately, I got confirmation during the summer that the Great Britain Sasakawa Foundation were willing to give me full-time funding. Since September, that has made it realistic for me to increase the pace of my work going into the later stages of the project.

I also had a couple of opportunities this year to present my work, first at the Japan Foundation/BAJS PhD workshop here in Edinburgh in February, then at the BAJS Conference in Cardiff in September. It was great to get experience of giving talks as well as meeting other people working on related and (much more often) very unrelated topics.

And finally, in between all these other activities, I was also writing these blog posts! I’ve found this helpful for getting some of my thoughts in order and briefly exploring topics that could make their way in some form into the commentary section of the thesis. I didn’t particularly plan to do it this way, but I’ve mostly gone one manga chapter at a time. As the translation process has sped up in the last few months, the chapters I write about have increasingly lagged behind the ones I translate. This isn’t necessarily a bad thing, because I find it quite useful really to return to something I haven’t touched in a few weeks and go over it with fresh eyes.

Anyway, I’m excited to say that because of that increased work rate on the translation, I actually finished translating the 40 chosen chapters a couple of weeks ago! It’s just a first draft and the job is by no means complete, but this is definitely a huge milestone. It adds up to more than 130,000 words – more than the limit for the whole thesis on its own – and even the blog posts so far come to about 28,000 on top of that.

That means one of the main things to work on in 2026 is narrowing down what exactly is going into the thesis. I’ll be looking closer at the translation to redraft it, examine the key points to concentrate on and pick out the chapters that will go into the thesis proper. There’ll be a lot of reading too, and a lot more blog posts to write to continue working out exactly what’s going into the commentary! I have another conference lined up in a few weeks’ time – I’m participating in a panel at InTO MANGA: Critical Paths in Manga Studies in Torino – and I’m also planning to apply to at least one other conference later in the year.

And with that, the last thing I want to say for this year is THANK YOU to everyone who has supported the project in any way! Please keep on reading as I continue talking about Torikae baya and sharing project updates in 2026. ❤

Thoughts from Episode 28: Suiren makes up her mind

Following the previous chapter’s visit to Uji to check in on Sara’s depressing storyline, we get the conclusion to Suiren’s dilemma in Heian-kyo. Everyone at court now knows that the Emperor has requested Suiren as a wife, so Suiren returns from her brief absence to give Togu an explanation. Togu assumes she has accepted the Emperor’s proposal and offers congratulations, having made an effort to get over her previous jealousy.

Following the previous chapter’s visit to Uji to check in on Sara’s depressing storyline, we get the conclusion to Suiren’s dilemma in Heian-kyo. Everyone at court now knows that the Emperor has requested Suiren as a wife, so Suiren returns from her brief absence to give Togu an explanation. Togu assumes she has accepted the Emperor’s proposal and offers congratulations, having made an effort to get over her previous jealousy.

But that isn’t really why Suiren has come! They have a conversation in private, while a dramatic storm conveniently shields them from eavesdroppers. After a roundabout conversation during which Suiren says she wants to leave and go looking for Sara, she finally reveals her biggest secret, even opening her robes to prove it to the disbelieving Togu. Togu faints, and when she wakes up she thinks Suiren is already gone – but she’s actually hung around to formally announce her departure. Leaving Togu distraught, Suiren finally makes her big exit, then goes to her parents to have her hair cut and put on Sara’s clothes, ready to begin the search for her missing brother.

Panels from volume 6, page 107.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

It says a lot about Torikae baya that the complex relationship between Suiren, a young woman harbouring a big secret about her personal background, and the adolescent Togu – who is also importantly her boss – is the healthiest romantic pairing in the story by a pretty big margin! Crucially, this is also a point where the manga diverges from the source material – not in the fact that it happens at all, but in how the characters and their relationship are portrayed.

Rosette F Willig, the translator of the original Torikaebaya monogatari into English, makes the case that the story effectively has just one main character, the chunagon, who is “played” by the two siblings one after another. The “sister” takes on the role until the situation becomes untenable, then the pair decide in Yoshino to switch places, so the “brother” then takes over. One impact of this is that the naishi no kami’s storyline is not explored in much detail. The “brother” simply becomes the naishi no kami, is smitten by the female Togu, and then can no longer continue in the position on account of having almost immediately impregnated her. Switching places to become the new chunagon is an easy decision for this version of the character, who takes quickly to life as a man, and isn’t even that devoted to Togu once other charming ladies become available!

Torikae baya’s Suiren is quite different, and plenty of time is devoted to showing that. Her shyness isn’t just a phase that she quickly grows out of, though her confidence does grow through her work as naishi no kami. And whereas her 12th-century (or thereabouts) counterpart’s attraction to Togu appears as some kind of masculine “instinct” coming to the surface, Suiren is instead shown to be scared that that could be the case. For example, in Episode 26, she panics after kissing Togu and says to herself: “I held Togu-sama as a man would.” It isn’t taken for granted here that she would want to live a man’s life given the choice, and she only takes Sara’s place when she feels she must.

When I wrote about Tsuwabuki finding out about Sara’s secret, I explained that Saito took what happens pretty quickly in Torikaebaya monogatari and expanded on it, with the effect of exploring characters’ emotions and changing how it all comes across to readers. The same thing basically happens in this case: instead of Togu finding out everything at once, her relationship with Suiren slowly develops, until Suiren reveals her secret and leaves, apparently never to return. This makes the characters more interesting, their storyline more romantic, and the overall plot less focused on how great it is to be a Heian gentleman.

Thoughts from Episode 27: The Uji Chapter

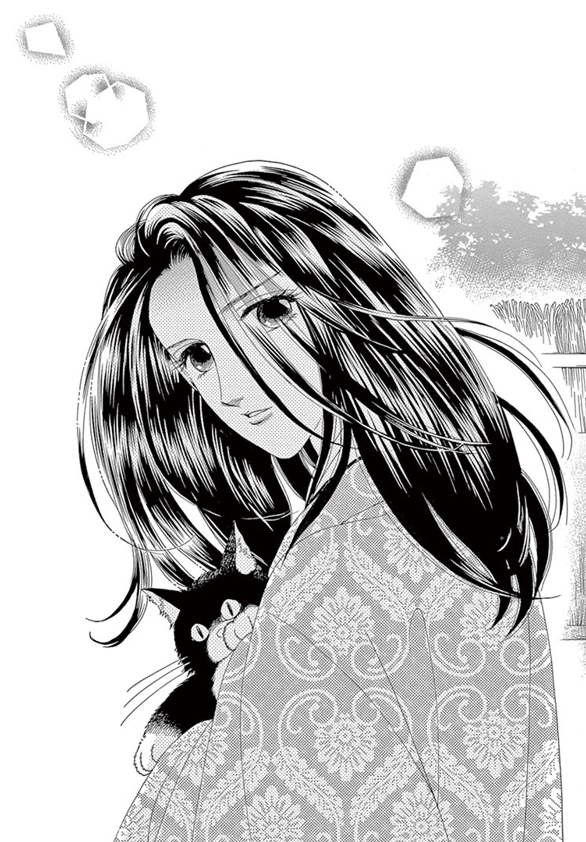

This chapter takes a break from Suiren’s spiralling situation in Heian-kyo to jump back a few weeks and pay a visit to Sara’s spiralled situation in Uji. The end of Episode 26 gave a brief glimpse at a woman (?) with a cat, who turned out to be none other than Sara. This time, we learn that since his sudden disappearance in the previous volume, Sara has been at Tsuwabuki’s villa in Uji, mainly under the care of Torako, Toramitsu and assorted servants.

This chapter takes a break from Suiren’s spiralling situation in Heian-kyo to jump back a few weeks and pay a visit to Sara’s spiralled situation in Uji. The end of Episode 26 gave a brief glimpse at a woman (?) with a cat, who turned out to be none other than Sara. This time, we learn that since his sudden disappearance in the previous volume, Sara has been at Tsuwabuki’s villa in Uji, mainly under the care of Torako, Toramitsu and assorted servants.

Tsuwabuki himself is also around some of the time, though he travels between Uji and his job in the capital. Smitten, he has a wonderful time dolling up Sara, who decides to grin and bear it until the baby is born. Then one day, Tsuwabuki receives a letter from Saemon, informing him that Shi no Hime – Sara’s wife who is scandalously also pregnant with Tsuwabuki’s child… – has been thrown out of her home. And when Tsuwabuki goes to visit Shi no Hime (at Sara’s insistence), he finds her feeble and hopeless, and is so moved by her situation that he vows to nurse her back to health. Finally, all alone in Uji, Sara can do nothing but compose a Sad Moon Poem™.

Panel from volume 6, page 43.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

Not for the first time, the story of Torikae baya (and its source material) bears some resemblance to The Tale of Genji. The final ten chapters of Genji are famously known as “the Uji chapters”, taking place after the titular character passes away and focusing instead on his sons, legitimate and illegitimate, as they compete over women in Uji. Now, Torikae baya’s own Uji chapter is Sara’s first appearance after he vanished from the capital, an act the story repeatedly associates with death. To cap it off, I’m even convinced that the title of Episode 24 (霧の迷い), when everyone is wondering what happened to Sara, is meant to bring to mind the title of the chapter where Genji dies (雲隠).

Another interesting aspect of this chapter is that after a pretty linear chronology up to now, the beginning of Sara’s time in Uji is presented as a flashback. Just as Suiren tells her parents she’s reached a decision in the previous chapter, we see “Sara-hime” holding a cat. Then after rewinding to Sara and Tsuwabuki’s arrival in Uji – specifically a month and a half earlier – and looking at Sara’s new life there, that cat is the signal that the story has caught up to where Episode 26 left off. It belongs to Aguri, who is going home after visiting Sara.

I find this interesting because it just isn’t a technique that Saito uses very often in this series! Events follow one after another, and most flashbacks are just a panel or two, often to scenes that we’ve already encountered once. The narrative jumps significantly forward in time at a few points, but rarely back. The only other similar part that I can think of happens in Episode 62, and even then it’s quite brief.

That’s not to say that the timeline is totally straightforward though. I talked before about the complexity of the story’s timeline and looking out for hints of how much time passes between events. Another complicating factor is that around this point in the story, we learn a bit more about things that happened in the past. Tucked in among the political gossip in Episode 26, Shikibu-kyo no Miya refers to a previous succession dispute which resulted in one of the parties withdrawing to Yoshino. Yoshino no Miya has himself hinted at having a dark past, such as when he implied that he had to be reborn after being exiled for his misdeeds.

At this stage, this is all we really know about this mysterious incident, and that it happened over ten years ago but not too much over ten years ago (ほんの十数年前, according to Shikibu-kyo). But we learn a bit more in the coming chapters, with implications for the timeline, for Yoshino, and for other characters in the story.

Thoughts from Episode 26: Togu or not Togu?

As I suggested last week, palace politics come up as an important thread in Episode 26. But first, if you thought things were awkward between Suiren and Togu after the shrine incident, wait until you see them now!

After the dramatic kiss that ended volume 5, Suiren quickly takes her leave, fearing that there is no return for her. She later calls in sick, prompting Togu to visit her, wanting to understand her feelings but not knowing how to ask. Togu instead asks about the story Suiren is writing – which sounds like it might resemble Torikae baya – and Suiren hastily stops her from reading it, causing her to leave.

As I suggested last week, palace politics come up as an important thread in Episode 26. But first, if you thought things were awkward between Suiren and Togu after the shrine incident, wait until you see them now!

After the dramatic kiss that ended volume 5, Suiren quickly takes her leave, fearing that there is no return for her. She later calls in sick, prompting Togu to visit her, wanting to understand her feelings but not knowing how to ask. Togu instead asks about the story Suiren is writing – which sounds like it might resemble Torikae baya – and Suiren hastily stops her from reading it, causing her to leave.

Elsewhere in the palace, complaints are ramping up about Togu not being available for ceremonies, while old man Fujiwara once again unsubtly hints that the Emperor should take Suiren as a wife and produce a new heir. And when Suiren later visits her parents, she learns that he has come around to that point of view too. Suiren decides she must do something… which we will find out more about in another episode.

There’s a lot of talk in this chapter about succession. We hear about the idea of replacing Togu, the official successor to the Emperor, who is still hoping to have a son one day. There’s even a brief discussion of having someone take over Sara’s “empty” position as General, but the Emperor is determined to wait until he returns.

As a reminder, the current Emperor has reigned since Episode 6, when there was a bit of shuffling around of roles. The previous Emperor abdicated, moving to a residence called the Suzakuin, which has also since been used as a sort of name for him. His younger brother, the then crown prince (or Togu 東宮) took his place, and Suzakuin’s daughter became Togu. That a girl took on that role was immediately considered notable – as I mentioned much much earlier, she is referred to as 女東宮 (girl crown prince), and the original Torikaebaya monogatari may be the first place this wording was used. And in the time since, that’s something that random court officials have been seen to take issue with. They scoff at her efforts to do her job, and when she isn’t around to do her job in this chapter, they insinuate (predictably) that it’s “that time of the month”.

Just as reigning female emperors were a rarity in Japanese history and always qualified through the male bloodline, the current Togu in Torikae baya is expected to just keep the seat warm as a temporary measure. The ideal scenario is that the Emperor will finally have a suitable (male) heir who can take over. Some hope that a new wife will help make that happen, but at this point in the story, there is now significant chat about replacing her immediately with an alternative. Even her allies don’t particularly want her remaining in the role, noting that as a female Togu, she is prevented from living a more normal life. While they want to protect her from criticism, they also feel it would be in her best interests to be relieved from the position.

However, as obvious as it seems that our Togu won’t remain the Togu indefinitely, this chapter also reminds us that she is in fact first in line to the throne. When Suiren panics after the kiss, she says to herself, “she’s the future Emperor!” There are later points as well that point out the degree of responsibility she has.

Incidentally, I keep saying “emperor” because the words used in Japanese (including 帝, 天皇) for the reigning monarch are the same, regardless of the gender of the officeholder – as is the case with “Togu”, for that matter. And I think this is part of why this Togu is such an interesting character! Just like Sara and Suiren, she is someone in a role supposedly inappropriate for her, but she still carries it out to the best of her ability.

But all this talk about imperial succession doesn’t just go away. This becomes a major storyline later on, and we also learn just now that it’s not the first time in living memory. When the people at court talk about replacing Togu in this chapter, Shikibu-kyo no Miya, a brother-in-law of the Emperor, seems a popular candidate, but he is quick to rule himself out. He reminds the others of a scandal ten-plus years earlier, when a succession dispute led a “good man” to leave the capital and go to Yoshino. Now who could that be? I’ll just leave it there for now and let you ponder the significance of that... 😉

Thoughts from Episode 25: The Heian rumour mill

We’ve reached the final chapter of volume 5, and as usual, it ends on a dramatic cliffhanger! But before that, it resolves the cliffhanger from last time. Kakumitsu has just discovered that his granddaughter was fathered by Tsuwabuki, and so he confronts Shi no Hime about this. Long story short, he kicks his pregnant daughter out of the house, along with her existing child and her attendant Saemon.

Meanwhile, Togu is being weird around Suiren after their awkward moment alone together last time. To make matters worse, the Emperor, worried about Sara and the impact of his disappearance on his family members (remember that the siblings’ father Marumitsu is basically the prime minister!), asks Togu to have Suiren join him on a boating trip. Suiren does attend, but sits behind a screen in near total silence while Marumitsu reminisces emotionally about Sara and Suiren’s first meeting.

We’ve reached the final chapter of volume 5, and as usual, it ends on a dramatic cliffhanger! But before that, it resolves the cliffhanger from last time. Kakumitsu has just discovered that his granddaughter was fathered by Tsuwabuki, and so he confronts Shi no Hime about this. Long story short, he kicks his pregnant daughter out of the house, along with her existing child and her attendant Saemon.

Meanwhile, Togu is being weird around Suiren after their awkward moment alone together last time. To make matters worse, the Emperor, worried about Sara and the impact of his disappearance on his family members (remember that the siblings’ father Marumitsu is basically the prime minister!), asks Togu to have Suiren join him on a boating trip. Suiren does attend, but sits behind a screen in near total silence while Marumitsu reminisces emotionally about Sara and Suiren’s first meeting.

However, when Suiren returns from the day out, she learns that Togu is in a foul mood. Suiren goes to see her and finds out that Togu was convinced that “boating” meant “boating 😏😏😏” and the prospect of Suiren not coming back that night upset her for some reason. The two get closer and closer, and finally kiss.

Once again, Sara is nowhere to be seen, except in flashbacks, and so we continue to see the sweet situation between Suiren and Togu develop. It’s worth noting that although there is also a relationship between their counterpart characters in the original Torikaebaya monogatari, the way it’s portrayed in this manga is different in some important ways – but that’s a topic I plan to delve into a bit later.

Panel from volume 5, page 159.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

What I want to focus on today is another thing that Episode 25 shows a lot of: rumours. While Saito devotes a lot of attention to the main characters and providing them with more complexity than they have in the source material, there are many aspects of Torikae baya that help to convey the atmosphere of the Heian court – from careful depictions of locations to a range of seasonal events. And another example of that is the significance of the rumour mill in characters’ lives.

Let’s go through some relevant cases from this week’s chapter. Kakumitsu had no idea that Shi no Hime and Tsuwabuki had had an affair until Shi no Hime’s sister Umetsubo decided to tell him about the latest hot gossip. Once he disowns Shi no Hime, it only spreads more rumours: men and women of the court are quick to conclude that Sara vanished as a result of his wife’s infidelity (not that they’ve figured out who the other man was). Soon, Togu’s other attendants are prodding Suiren about the topic, and even the Emperor hears “awful rumours” (心ない噂) relating to Sara. And of course, when he invites Suiren to join him on his boat, the Emperor must know that this will make people’s imaginations run wild too, especially since Suiren’s grandfather has been advocating for the Emperor to take her as a wife for months at this point. Even Marumitsu’s story about Sara and Suiren as children – despite being about an event the readers are familiar with – is something he didn’t witness himself, so he can only report what he heard from a servant who was there at the time.

So why does this matter apart from providing atmosphere? I think it’s helpful as a reminder of how things operate in a political environment like the imperial court, and how that impacts plot developments. It’s a lot easier to say “these misunderstandings could be avoided if people just talked to each other!” if a story is set in a school or something, but remember that this is the government. You can expect people to have hushed conversations not just because they love a bit of relationship gossip, but also for the sake of behind-the-scenes political shenanigans. And when a lot of people aren’t really expected to see one another directly, it’s no wonder that hearsay is all they know.

This point about politics will only become more significant in Volume 6 and beyond. You may remember that some people are unconvinced by Togu’s aptitude for her position because she’s a girl. The growing movement to remove her soon becomes a major plot point – and I might even have some more to say about that next time!

Thoughts from Episode 24: Whither the weather?

This chapter covers the immediate aftermath of Sara’s sudden disappearance: his friends are confused, Shi no Hime feels ashamed, Suiren sees Sara in her dreams, and Marumitsu is so upset he can’t contain himself, even in front of the Emperor. Even we don’t see any sign of Sara, apart from in Suiren and the Emperor’s imaginations. Suiren writes to Yoshino no Miya, who doesn’t know where he is either.

But Suiren doesn’t have time to mope, because she has to accompany Togu into the mountains to perform prayers. On the way, the rain picks up and the men in the party slip and drop Togu’s palanquin – luckily Togu gets out just in time! While they go to recover it, Suiren and the ladies walk with Togu through the mist until they come across a shrine, where Suiren and Togu are temporarily left alone together.

This chapter covers the immediate aftermath of Sara’s sudden disappearance: his friends are confused, Shi no Hime feels ashamed, Suiren sees Sara in her dreams, and Marumitsu is so upset he can’t contain himself, even in front of the Emperor. Even we don’t see any sign of Sara, apart from in Suiren and the Emperor’s imaginations. Suiren writes to Yoshino no Miya, who doesn’t know where he is either.

But Suiren doesn’t have time to mope, because she has to accompany Togu into the mountains to perform prayers. On the way, the rain picks up and the men in the party slip and drop Togu’s palanquin – luckily Togu gets out just in time! While they go to recover it, Suiren and the ladies walk with Togu through the mist until they come across a shrine, where Suiren and Togu are temporarily left alone together. Togu wants Suiren to check her leg for swelling, which soon ends in tension and blushing, before the party regroups and Togu becomes oddly distant.

Elsewhere, Kakumitsu is frantic about his missing son-in-law, irritating his daughter Umetsubo, Sara’s leading hater. In fact, she’s so annoyed that she decides to cause problems by revealing the gossip about her sister Shi no Hime. Stunned, Kakumitsu runs off to see his granddaughter Yukihime, and realises that sure enough, she doesn’t look like Sara but does look like Tsuwabuki.

Suiren carries Togu in the mist.

Panel from volume 5, page 135. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

Episode 24 kicks off a section in the story where we mainly spend time with Suiren for a few consecutive chapters. The chapter title is “Obscured by Mist”, originally 霧の迷い (kiri no mayoi). It’s an expression that can be used literally – a situation where one can’t see through the mist – or figuratively, referring to emotional conflict or anxiety.

And in the context of this chapter, I also feel like it carries a bit of a double meaning. One storyline sees Suiren and Togu lost in the mist, developing feelings for each other, but at the same time, this expression also seems to fit the way Sara vanishes without a trace. Marumitsu considers whether Sara might’ve been whisked away by a supernatural entity – using the term 神隠し (kamikakushi) that you might know from a film and which happens to be associated with beings like tengu. And Sara’s sudden disappearance accompanied by a weather metaphor in the chapter title also reminds me of The Tale of Genji, where the hero’s death is represented by a chapter that consists only of the title “Vanished into the Clouds” (雲隠, kumogakure) after which the story continues with his descendants instead.

So today, I’d like to say a little more about the weather in Torikae baya. Our attention is mainly drawn to the weather when it is bad, and particularly when that causes a problem in the story. For example, inclement weather derails the outing in this week’s chapter as well as leading Sara and Suiren to their dramatic meeting with Yoshino no Miya much earlier. It is also the reason for Sara’s recent work, where he had to manage river flooding.

On the other hand, sometimes bad weather has more convenient results. Sudden gusts of wind accompany the Emperor on multiple occasions, granting him opportunities to see people otherwise hidden. The then-Togu prays for rain to hide the ominous eclipse. In a chapter after this one, a storm provides helpful background noise to prevent eavesdroppers from hearing an intimate conversation. Similarly, it rains heavily outside during the scene where Sara confronts Tsuwabuki about his affair with Shi no Hime and Tsuwabuki ends up getting a hint about Sara’s own secret; it isn’t made clear that the rain stops people from listening in on this conversation, but the connection is there.

And as with the title of this chapter, there are metaphorical examples too. I said before that Shi no Hime compares Sara to spring (this association came up again much more recently too) and Tsuwabuki to autumn, but she doesn’t only mention seasons. Sara’s affection is like gentle sunlight, while Tsuwabuki’s is a storm. Sara, without whom “it was as if a light had been extinguished in the palace”, is compared with the sun at other points too, his bright demeanour contrasting with Suiren’s. That last point links also to yin and yang, but I’m afraid that as I said the last time I brought that up, exploring that route better will have to wait for another day!

Thoughts from Episode 23: The Flower Festival

The cherry trees are in full bloom on Sara’s last day of work at the imperial court, and he is making a point of going around talking to everybody. By now, he’s clearly getting tired quite quickly, so he has help from Aguri’s daughter Torako and son Toramitsu, whom he’s known since childhood. The palace is in party mood, with Togu asking to see Sara and Suiren together – prompting tears of joy from their father – and court officials reciting Chinese poetry (唐歌, karauta as they call it in the manga). Sara’s recitation is so moving that the Emperor sends him a robe as a gift and later requests a musical performance from him and Suiren as the day comes to an end. Sara instead plays the flute alone and thinks back on his time as a court gentleman.

The cherry trees are in full bloom on Sara’s last day of work at the imperial court, and he is making a point of going around talking to everybody. By now, he’s clearly getting tired quite quickly, so he has help from Aguri’s daughter Torako and son Toramitsu, whom he’s known since childhood. The palace is in party mood, with Togu asking to see Sara and Suiren together – prompting tears of joy from their father – and court officials reciting Chinese poetry (唐歌, karauta as they call it in the manga). Sara’s recitation is so moving that the Emperor sends him a robe as a gift and later requests a musical performance from him and Suiren as the day comes to an end. Sara instead plays the flute alone and thinks back on his time as a court gentleman.

Soon, the Emperor decides Sara deserves a promotion to General (右大将) of the Imperial Guards, but Sara is nowhere to be seen. Unbeknownst to everyone present, he’s already leaving under cover of darkness, with Torako and Toramitsu leading him to an ox-drawn carriage. There, much to his displeasure, he finds Tsuwabuki – as it turns out, Aguri revealed the plans to him and he insisted on helping. In the end, Sara is too exhausted to keep fighting, and the group heads off for Tsuwabuki’s villa in Uji.

I don’t normally do this, but the title of today’s blog post, The Flower Festival, is the same as the chapter title for Episode 23. In Japanese, it’s hana no utage (花の宴), which, like several other chapter titles, is also the title of a chapter in The Tale of Genji. I made an exception this time because it’s particularly apt: not only does the chapter revolve around a flower viewing party in the palace, but it’s also full of meaningful references to flowers.

Title page of Episode 23 from volume 5, page 79.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

In Episode 12, Sara’s personality was compared to spring. Fittingly, on the day he bows out from court service, he’s given the theme of “spring” in the poetry recital. He tastefully recites two consecutive poems by Heian blorbo Bai Juyi from the “last day of the third month” (that is, the end of spring) section of the Wakan roeishu, a famous anthology of Japanese and Chinese poetry. The way this is presented in the manga is as he recites it, not in Chinese but using kanbun kundoku, a traditional of not exactly translating the original poem but converting it to (classical) Japanese grammar. And that’s how we get this:

春 留むるに 春 住まらず

春 帰って 人 寂漠たり

風を厭うに 風 定まらず

風 起って 花 蕭索たり

And this:

竹院に 君 静かにして 永日をけすならん

花亭に 我 酔うて 残んの春を 送る

Now, I can’t just read Chinese as-is, but it does have something distinctive about it, so in my translation, I wanted it to sound a bit different from how I’ve translated the Japanese poems so far. With that in mind, I again took advantage of the fact that we’re shown a classical Japanese and a modern Japanese version. While my translation of the modern Japanese gave me a chance to flesh it out and explain it more, in the first versions I tried to stick quite closely to order of the characters in the original Chinese poems and avoid too many extraneous words in an effort to express their structure. So the first poem ended up like this:

Hold back spring, but it will not stay.

Spring leaves; we are all alone.

Despise the wind, but it will not abate.

Wind rises; flowers are desolate.

(Even if one tries to hold onto spring, it will not remain.

Spring goes away and people reflect quietly on their solitude.

Even if one hates the wind that scatters the flowers, it will not die down.

The petals falling as the wind blows are all the more saddening.)

And the second one (my personal preference!):

You, serene, in a house with bamboo, as the long day dwindles.

I, drunk, in a hut with flowers, watch spring leave.

(In a quiet manor house, surrounded by bamboo,

you spend this long day as spring comes to an end.

In a small house, surrounded by flowers,

I become drunk and gaze out at what little remains of spring.)

Something you’ll notice is that these both make reference to flowers. The first feels particularly significant in Episode 23, with the idea that the wind sadly blows all the blossoms away aligning with some of the other imagery in this chapter. They also share a melancholic description of the passing away of spring. We can think of spring as representing Sara in the eyes of those who care about him, and also in his eyes as the life he’s led so far – something to be missed as it imminently departs.

Other touching references to flowers come up throughout the day, like early on when Sara speaks to a lady who says the flowers are “at their very peak of beauty today” (今日が満開の美しさですわね) and at sunset when Sara laments the end of the day and an official tells him “this is when the blossoms look best” (桜が一番きれいに見える時ぞ). On the surface, these are about what is literally happening, but in the overall narrative, they’re obviously about Sara too.

And the clearest such connection comes at the start, when Sara tells us, “Today is the day I disappear” (今日は 私が散る日). He used the word 散る in Chapter 22 as well, when deciding that he would go out with a bang: “Brilliantly, colourfully, just like a flower, I will fall” (華々しく煌らかに 花のように 散ってみせよう)*. I find myself translating this word differently each time – and it does come up again after this too – because of its double meaning. On the one hand, it is literally “to fall” or “to scatter” as petals might, but it also means “to die nobly”. Sara intends to do as Yoshino no Miya advised him, and “die” so he can live again.

Sara’s repeated use of 散る in reference to himself also calls to mind his name. The sarasoju (沙羅双樹), or sal tree, or natsutsubaki (not all necessarily the same plant!) is known for its briefly blooming flowers, and is associated both with the death of the Buddha and with the opening lines of The Tale of the Heike, a story full of noble death. Frankly, I think I’d better write an entire post just about his name one of these days!

But basically, 散る is just about the most evocative way Sara could describe his departure from the Heian court. And it casts a different light on all the mentions of flowers throughout this flowery chapter!

*I particularly love this line because it feels like a twist on “Let’s live our lives heroically, let’s live them with style” (潔く、格好良く生きて行こう– the similarity is clearer in Japanese!)

Thoughts from Episode 22: A busy New Year

After a stunned silence following Sara’s bombshell reveal last time, Tsuwabuki becomes quite excited about the prospect of them having a baby together. He tells Sara to “go back” to being a woman (😬) and suggests they get married. Sara, realising that Tsuwabuki is dreaming of a scenario where he can take both his pregnant partners as his wives, then claims that the story about the pregnancy was just a test, and departs.

A new year begins, and with it comes many important court ceremonies. Sara’s interactions with the Emperor inspire him to persevere as a court official, until one Buddhist ritual where a monk announces that something unclean is present. It turns out a dog has entered the hall, but this doesn’t quell Sara’s worries that if he remains at court, it could have disastrous karmic effects.

After a stunned silence following Sara’s bombshell reveal last time, Tsuwabuki becomes quite excited about the prospect of them having a baby together. He tells Sara to “go back” to being a woman (😬) and suggests they get married. Sara, realising that Tsuwabuki is dreaming of a scenario where he can take both his pregnant partners as his wives, then claims that the story about the pregnancy was just a test, and departs.

A new year begins, and with it comes many important court ceremonies. Sara’s interactions with the Emperor inspire him to persevere as a court official, until one Buddhist ritual where a monk announces that something unclean is present. It turns out a dog has entered the hall, but this doesn’t quell Sara’s worries that if he remains at court, it could have disastrous karmic effects.

Sara goes to Aguri, his old wetnurse, to tell her about his situation and request her assistance. He plans to quit his job, have the baby, then decide on what to do in the future, but doesn’t want either Tsuwabuki or his parents to know. Then, when Sara returns to court to begin his final weeks as a nobleman, he’s so uncharacteristically flashy and charming that Tsuwabuki is convinced something is out of the ordinary, and goes to seek answers from Aguri himself.

A few weeks ago, I wrote a little overview of the forms of marriage (and divorce) available to Heian aristocrats. That comes up briefly in this chapter too, when Tsuwabuki casually proposes to Sara. The situation he wants to create – whether he’s consciously aware of it or not – is what I called the third type of marriage, where the lucky man installs his wives in his own residence. In the afterword where Saito explains the different types of marriage, she also specifies that this is what Tsuwabuki longs for. It’s the kind of setup that the protagonist eventually enjoys in The Tale of Genji, tying in with what we know about Tsuwabuki’s efforts to live up to that particular ideal of masculinity.

Now, apart from marriage, another area of Heian court customs that shows up in a big way in this chapter is seasonal ceremonies. New Year is important in the palace calendar, and this is true today as well, even if it’s now based on the Gregorian calendar instead. A series of rituals took place over the first few weeks of the year, keeping everyone at court busy, especially the Emperor himself.

Several court ceremonies following New Year.

Panels from volume 5, page 55. ©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

How these events are presented in the Torikae baya manga varies somewhat. Sometimes, as with a few of the ceremonies in this chapter, Saito provides a representative moment along with a heading giving the name of the event. For more plot-significant examples, we’re treated to many more views of the ceremony taking place, and there may be a sidenote explaining what it was about – one case of this is the Komahiki ceremony back in Episode 2.

Sometimes, Saito goes a little further, not just showing the event taking place and giving its name, but also providing lengthier narration to explain what the ceremony entailed and why it mattered. She does this with, for example, the Iba-hajime, an archery contest in Episode 19, as well as the Go-saie, the big assembly of monks and priests where Sara begins to panic this time around.

Here's how I translated the explanation of the Go-saie:

The Go-saie was a vital ceremony where important monks of the six Buddhist sects

met to discuss and give sermons.

Except on occasions where an Empress reigned,

only men were permitted to take part.

Now, the story would work just as easily without this explanation. We’re told that the Go-saie is a no-girls-allowed event, but the way the scene pans out, that becomes pretty clear anyway. But having those explanations does add something! The inclusion of the seasonal events themselves gives a sense of the passage of time and a flavour of Heian court society, and it shows the degree of background research involved in writing the manga in the first place. By also giving these occasional descriptions of ceremonies – as well as things like the afterwords that go into more detail about specific cultural details like marriage customs – Saito reveals more of that research, and brings in an educational dimension too. She had to learn a lot to put Torikae baya together, and in reading it, we can learn a lot too!

Thoughts from Episode 21: You only live twice

At the end of the previous chapter – and volume – Sara had what seemed horribly like morning sickness. This time, he goes to see his former wetnurse Aguri, whom he used to visit for a few days every month until very recently, to subtly ask about the typical symptoms of pregnancy. He soon concludes that it is just as he feared, then takes a week off from work to go and see Yoshino no Miya, the only person he can think to confide in.

At the end of the previous chapter – and volume – Sara had what seemed horribly like morning sickness. This time, he goes to see his former wetnurse Aguri, whom he used to visit for a few days every month until very recently, to subtly ask about the typical symptoms of pregnancy. He soon concludes that it is just as he feared, then takes a week off from work to go and see Yoshino no Miya, the only person he can think to confide in.

Sara tells Yoshino he wants to die, but Yoshino tries to change his mind. He suggests that Sara has the ability to “die” once and then live a second life, implying that he has done something similar himself. In the end, Sara is inspired to persevere, but remains unsure of what to do.

Meanwhile, Tsuwabuki is indiscreetly snooping, and in his attempts to find out where Sara is, he ends up speaking to Shikibu-kyo no Miya, who reveals that Sara had just returned to speak to him. In fact, Sara is listening right at that moment, and isn’t too pleased about Tsuwabuki’s loud mouth. Afterwards, they have an argument, Sara collapses, and when Tsuwabuki insists on fetching a doctor, Sara blurts out the truth about his pregnancy.

Since early in the story, fate has been an important recurring theme in Torikae baya. Sara and Suiren’s peculiarities and their troubles are attributed to karma from their past lives, and when things go wrong, it can feel a lot like they’re helpless to make it better. But at the same time, the issue of fate is an area where the manga actually challenges the source material a bit: a topic that came up when I spoke to Saito was that the original story has quite a stern Buddhist outlook and that she wanted to make her version more “positive”.

That’s something that comes across strongly in this chapter. When Sara realises what has happened and questions what to do, he believes there’s no way he can go on living. He thinks of the tengu that supposedly cursed him and Suiren – the most prominent representative of fate in the manga – and asks if it is a shinigami, coming to take him away.

Panel from volume 5, page 24.

©Chiho Saito/Shogakukan

Immediately afterwards, he visits Yoshino no Miya, whose mysterious power to predict the future also reflects the significance of fate. Indeed, Yoshino is associated with the tengu, but an important difference is that he emphasises Sara’s power to make his own decisions. Sara, despairing, wants to be told what to do, and he responds:

I will not tell you whether to have the baby,

or whether to join the priesthood!

What you do with the rest of your life

is something you must decide for yourself!

As much as Yoshino uses divination to claim that Sara is destined for a bright future, he also suggests that it’s up to Sara to shape that destiny. He tells Sara he’s reached a fork in the road (分かれ道 – this is also the title of the chapter!) where he needs to decide on a new course of action. And in Yoshino’s idea about living one life and then another, there is the suggestion that even one’s ultimate fate needn’t be truly final.

And so, even though the siblings still go through plenty of hardship in Saito’s version of the story, they’re portrayed as having the agency to control how their lives pan out. They ultimately make their own decisions, for better or for worse.